It’s Halloween, and there is no better day to share some of the History Center’s spookiest artifacts.

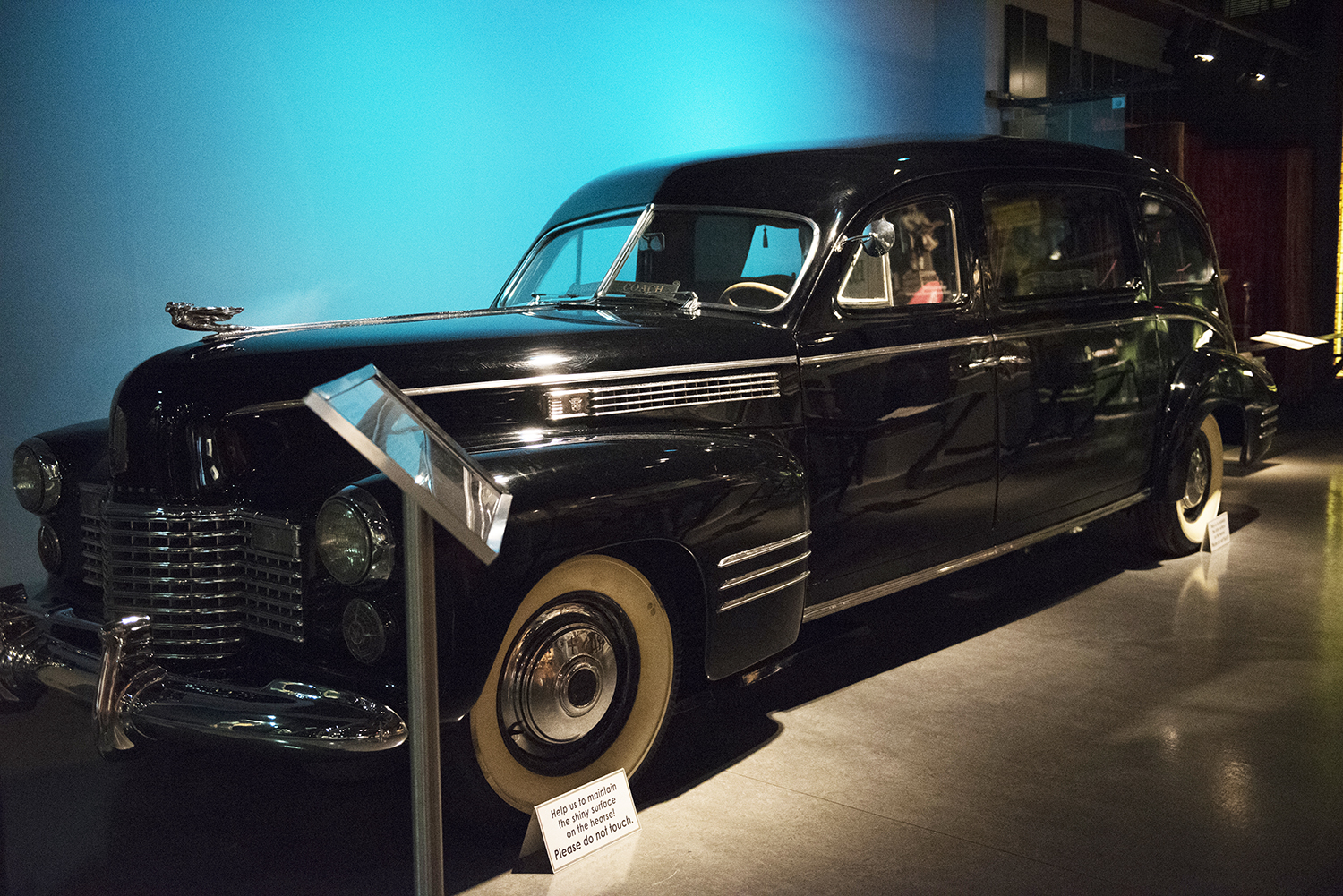

Gaines Funeral Home hearse, Cadillac, 1941.

Partial gift of Barbara and Frank Stagno.

Gaines Funeral Home was founded by George W. Gaines in Homestead, Pa. in 1919. The funeral home moved to various locations in Pittsburgh until 1929, when it took over the former Mt. Ararat Baptist Church in Pittsburgh’s East End.

This specific hearse was one of a fleet of limousines and hearses owned by Gaines from the 1940s on. A model Sixty Special made for commercial use, it is equipped with a record player under the dash board to broadcast hymns as the car moved in procession.

Tree trunk from Chickamauga Battlefield, 1863.

This shell- and bullet-ridden tree trunk stood 35 yards in front of the battle line of the 78th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the 1863 Battle of Chickamauga, which was known as the “Gettysburg of the West.” With 16,170 Union and 18,454 Confederate casualties, the Battle of Chickamauga was the second costliest battle of the Civil War, ranking only behind Gettysburg, and was by far the deadliest battle fought in the West. The campaign and major battle take their name from West Chickamauga Creek.

According to popular accounts, Col. Archibald Blakely, the regimental commander, returned after the war to obtain a relic from the battlefield. He brought the trunk back to Pittsburgh as a reminder of his regiment’s involvement in the battle.

Miner’s helmet, c. 1948.

Gift of Richard Furgiuele.

Richard Furgiuele owes his life to this helmet.

While at work at the Redlands Coal Company in Indiana County, Pa., Furgiuele’s head became lodged between the low ceiling and the steering wheel of his vehicle. It took rescue workers more than an hour to free him and only his helmet, not his head, was damaged.

Storage Jar, c. 1885.

Gift of Bernard and Joanne Vavrek.

Okay, so what is so creepy about a jar? The maker of this one may have met a sad end. Only a few potters could make and fire large and heavy ware like this. Robert T. Williams bought the New Geneva Pottery Works in 1882 and ran a prosperous business as the industry declined in the region. He routinely sold to towns up and down the Monongahela River.

But during a business trip to Pittsburgh in 1895, Williams disappeared. He was last seen crossing over the river to Homestead on his way to Brownsville. He was eventually supposed to meet a business partner in McKeesport but never showed up.

A Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article dated Tuesday, Jan. 29, 1895 reads: “The man in charge of the wharf boat says he heard a noise on the outside, as of a man walking around the edge of the boat, but as it was nothing unusual he paid no heed to it and went to sleep. The fear is that William stepped or fell off into the river and was drowned. He wore a large overcoat and heavy clothes and though he was an excellent swimmer his heavy clothing might have dragged him to the bottom of the river.”

His mysterious disappearance was never solved. While some believed he may have stepped off the wharf boat in McKeesport and drowned, as the Post-Gazette article suggests, others believed he was murdered.

Czech Puppets, 1920s.

Gift of Thomas Getting & Marcia Sutherland.

As most forms of artistic expression were suppressed during periods of foreign occupation, puppetry, overlooked as a “folk” art, became a popular method of spreading political opposition. These puppets were purchased by the Getting family to educate their children and friends about the culture of Czechoslovakia.

Undisputed leaders of puppetry in Europe, the Czech puppeteers also had a tradition of radical puppetry. When the Czech language was banned by the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in the 19th century puppeteers continued to perform in Czech as an act of defiance. During Nazi occupation, Czech puppeteers organized illegal underground performances in homes and basements with anti-fascist themes, called “daisies.” In the concentration camps, Czech women made puppet shows from scraps to keep up their morale. Eventually, the Nazis suppressed all Czech puppetry and more than 100 skilled puppeteers died under torture in the camps.

Next time you visit the museum, check out the Special Collections gallery on the fourth floor to see these artifacts in person.