Yiddish theater had a peripatetic existence in Pittsburgh before the opening of Lando’s Theatre in October 1928. Visiting companies put on shows wherever they could find space to rent, and audiences followed productions to theaters and halls around the city.

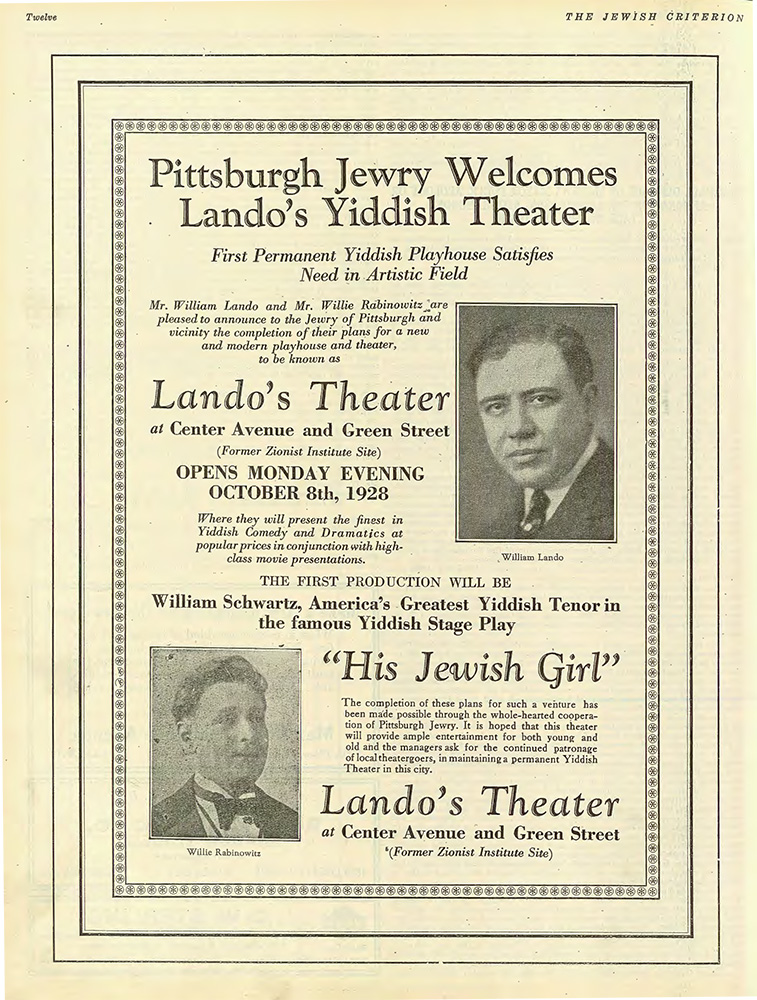

As the first dedicated home for Yiddish theater in Pittsburgh, Lando’s hoped to become a regional center for Jewish art and culture. “The purpose of this project is to put into effect a playhouse where parents with their children will see high type amusement of the better kind, also where the younger folks will learn Jewish customs and ethics,” the Jewish Criterion noted in a promotional brief shortly before the grand opening of the theater. A second brief claimed that construction of a theater was one of the conditions of the sale of the property, which had previously been the site of the Zionist Institute. (The location of the theater at the corner of Center Avenue and Green Street is now a landscaped promenade running between Hill House Association and One Hope Square.) The 1,000-seat theater showed Yiddish plays almost nightly and first-run movies on Jewish themes at least once a week. The theater also became a gathering place for Jewish events.

Lando’s was initially a partnership between businessman William Lando and producer Willie Rabinowitz. Little is known about Rabinowitz today, despite a claim in the Jewish Criterion that he was “for twenty-five years one of the foremost actors and producers in the United States and Canada.” Lando was a Romanian immigrant who started a successful real estate operation. (The Lando Building, on Penn Avenue downtown, was among his properties.) He was president of Ohr Chodesh Congregation, known back then as the “Romanian shul” for its ethnic affiliation and as the “Roberts Street shul” for its original location in the Hill District. (The congregation is now New Light Congregation and located in Squirrel Hill.) He regularly made his theater available to his fellow Romanian Jews, especially as the atrocities of World War II became known.

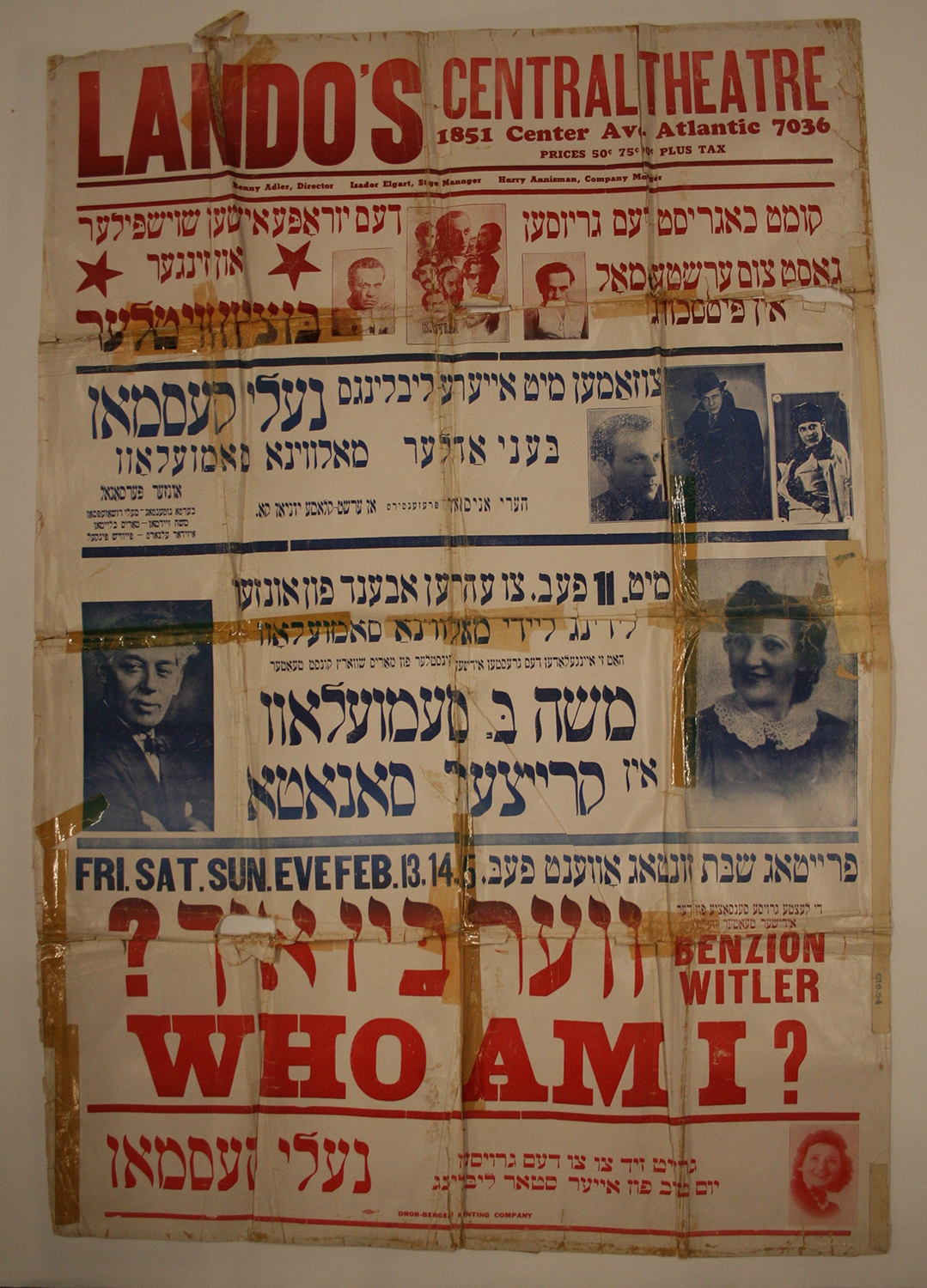

Until recently, the only documentation of Lando’s Theatre in the Detre Library & Archives was a small photograph of its exterior. But earlier this year, the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives received two Lando’s Theatre posters by Lowell Lustig, whose grandmother Malvina Samuilov acted in both productions. The posters need the loving touch of a skilled conservationist, but despite their creases, rips, and yellowing tape, you can make out details that illuminate the world of Yiddish theater in Pittsburgh and offer many pathways for future researchers to follow.

For starters, there’s the name: Lando’s Central Theatre. The institution was founded as Lando’s Theatre in 1928 but started using the name Lando’s Grand Theatre as early as 1932 and had switched to Lando’s Central Theatre by 1940. The changes were never explained but may have been a response to changing demographics in the Hill District.

Over the course of the 1930s, as Jewish migration to Squirrel Hill, Greenfield, the East End, Oakland, and Shadyside increased, the Hill District lost its half-century distinction as the center of Jewish life in Pittsburgh. According to a Jewish population study conducted in 1938, the Hill District was only home to about 11,000 of the approximately 53,000 Jews living in the city. By 1940, even Lando had left the upper Hill District to live on Negley Avenue in the East End. Describing his theater as “grand” and then “central,” a pair of adjectives with diminishing ambitions, may have been an attempt to lure Jews from eastern neighborhoods back to the Hill District for an evening of entertainment.

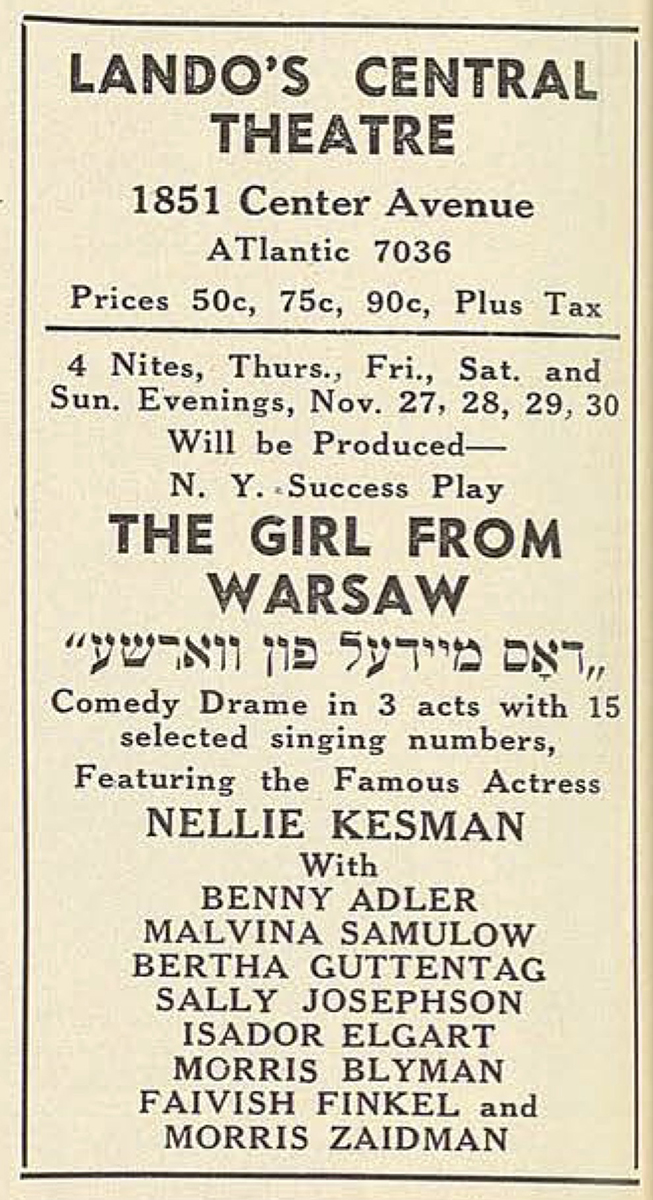

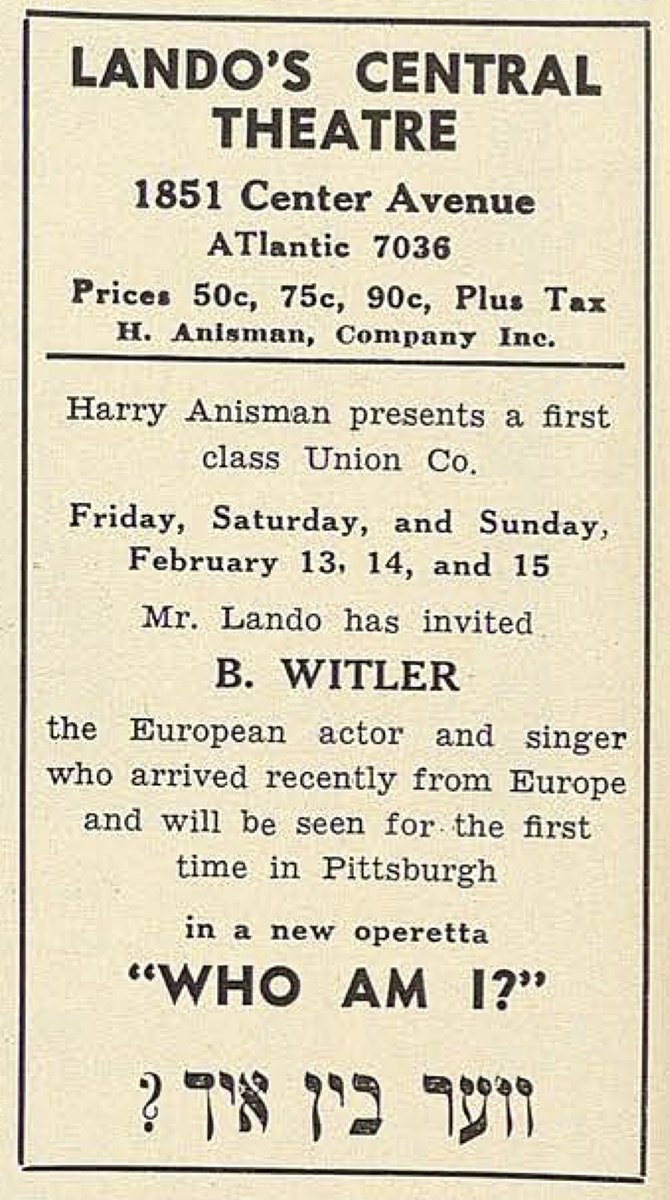

The posters appear to document productions from the final season at Lando’s. “The Girl From Warsaw” had a four-night run from Nov. 27-30, 1941, and “Who Am I?” played from Feb. 13-15, 1942. The last advertisement for a Lando’s production appeared in the Jewish Criterion in late April 1942. The Lando Realty Company put the building up for rent in February 1944, and Lando began producing plays at other theaters that November.

The cast and crew information on these posters provides another avenue for study.

The first stop for any research into Yiddish theater personalities is the “Encyclopedia of Jewish Theater,” an unfinished seven-volume reference guide lovingly created by Zalmen Zylbercweig over the 50 years preceding his death in 1972. Zylbercweig often solicited information directly from the people involved in productions, and Malvina Samuilov provided short biographical profiles about herself as well as her third husband, Harry Anisman, who is listed as the “company manager” on both posters.

Samuilov’s accounts have all the bohemian romance and tragedy one would hope to find in the lives of theater folk. She was born in Romania as Molly Ferkoyf and followed her actor parents to the United States as a child. A trained opera singer, she drifted into the theater and briefly went by the stage name Mollie Magazine, after her first husband Sam Magazine (who she would remarry four decades later, after retiring from the stage). She married Anisman after working with him in Winnipeg but assumed the name Samuilov after her stepfather Moshe Baer Samuilov, who also appears on one of the posters.

Harry Anisman (1893-1950) was born in Kiev to “semi-well-to-do parents” and ran away from home in his teens to work odd jobs and apprentice in a children’s theater and as a “buff comic.” He lost his first wife, actress Rukhele Klein, and one of their children to a cholera epidemic. He performed with Yiddish theater troupes in Constantinople and Paris before immigrating to the United States in 1925 and performing in Detroit, Winnipeg, and Brooklyn before arriving in Pittsburgh in the late 1920s. Arthritis forced him into small roles and then behind the scenes and finally into a convalescent home.

The theater required Anisman and Samuilov to live nomadic lives. Lustig said their daughter Diana Anisman, his mother, had lived in nine cities by the time she turned 17.

Anisman, Samuilov, and the other actors, directors, and managers listed on these posters were part of a stock company that performed at Lando’s Theatre throughout both the 1940-‘41 and 1941-‘42 season. Other actors in the troupe include Benny Adler, Morris Blyman, Isador Elgart, Bertha Guttentag, Sally Josephson, and Morris Zaidman. (All these actors and actresses suffered a fate common to Yiddish performers: inconsistent spellings of their names in English.) Top billing often went to the popular actress and singer Nellie Kesman. In retrospect, the most famous actor shown on either of these posters is the least prominently displayed. Philip “Fyvush” Finkel (1922-2016) is best known for his roles on the television series “Picket Fences” and “Boston Public,” and for his late-career return to Yiddish acting in a cameo for the film “A Serious Man.”

Other details worthy of additional research include the Drob-Berger Printing Company listed at the bottom of each poster, the ticket prices listed at the top, and the overall operations of a company where performers also assumed directing and managerial roles.

Eric Lidji is the director of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives at the Heinz History Center.