Ah summer, when everyone seeks to break their routine and relax. Today might be a better day than usual to do that, since it is officially “National Relaxation Day.” The day was coined by 9-year-old Sean Moeller, an Iowa fourth-grader who decided in August 1985 that “people think too much about working.”[1]

Americans have debated the impact of too much work since the late 1800s. The debate contributed to the rise of the modern paid vacation and emerged out of the reality of cities like Pittsburgh, urban places that churned with industry and business. (Although ironically by the 1980s, many Pittsburghers were probably more worried about not working as the region’s steel industry hit its lowest ebb.)

Who needs rest?

The word “relaxation,” meaning “relief from hard work,” first appeared in the 1540s. But for the next three centuries, most people were too busy with their daily lives to worry about taking time off. In agricultural societies such as the United States through the mid-1800s, seasonal activities created periods of intense labor and then down times to catch up on other things. One day a week was devoted to the scriptural rest of the Sabbath. Other than that, time was too valuable to waste on idle leisure. Even children’s objects stressed the value of time.

The stress of city living

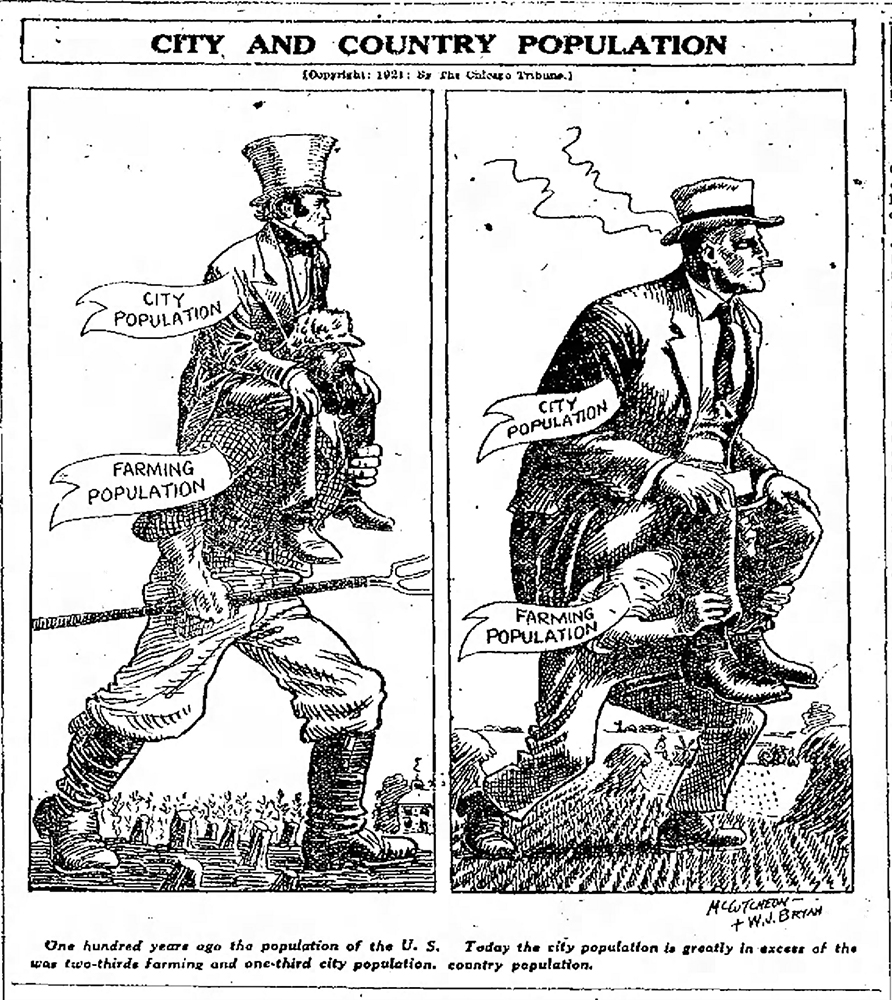

As the country industrialized, the way people lived and worked changed. Six-day regimented work weeks, repetitive labor, white collar jobs, and the chaos and noise of the crowded city became increasingly common. By 1920, for the first time the U.S. Census recorded a nation where more than 50 percent of the population lived in urban areas.

Not everyone thought this was a good thing. Cultural critics found city life disturbing. The jobs, the noise, new technology, new vehicles, life moving faster than ever anticipated; these things “depleted nervous energy.” People believed that mental activities used more energy than physical labor, so white collar jobs were regarded as especially taxing, particularly for all the young women entering the workforce. They even coined a term for it: “Neurasthenia,” or nervous exhaustion from the stresses of modern life. Some called it “the great American disease.” In 1910, President William Howard Taft even proposed that every American adult really needed two to three months of vacation per year to recover from the “nervous strain” of modern life. Not surprisingly, most business leaders didn’t favor the idea.

“Paid to play” catches on

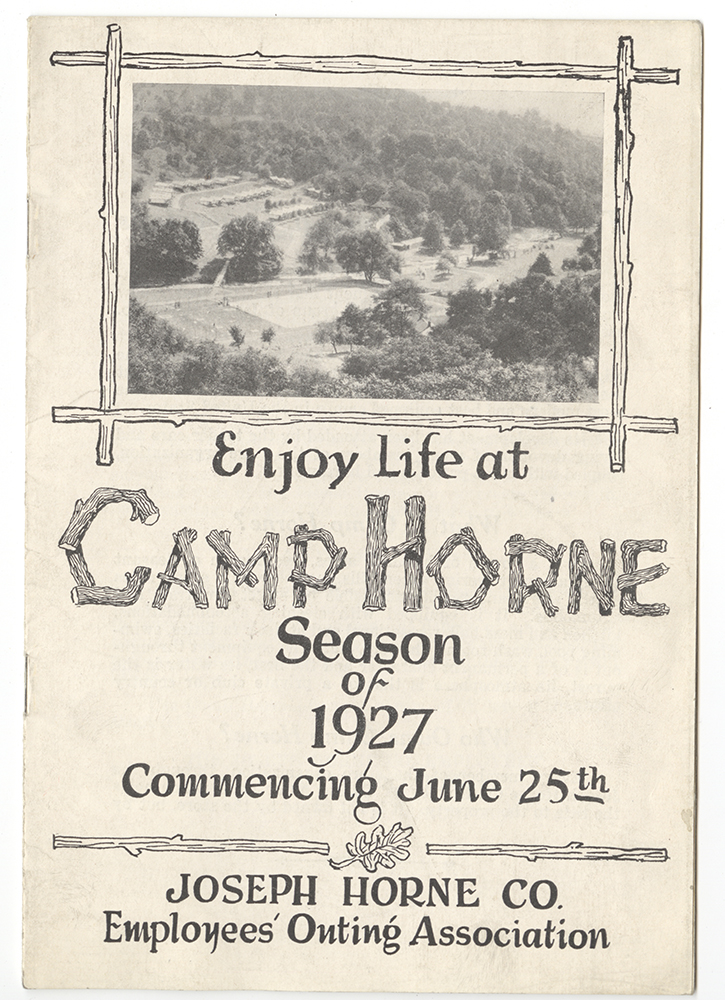

Growing social reform in the early 1900s and the impact of World War I, especially studies focused on the impact of fatigue, put vacation in a new light. More employers began offering some sort of leave, although it wasn’t often paid. (When factories shut down for a week or two in summer, technically everyone was off, but with no compensation.) Some even set up programs where employees could enjoy a week of camping or relaxing at a company-sponsored setting for a reduced rate. Camp Horne, run by the Joseph Horne Company, became a well-known example in Pittsburgh. (Read more on a previous blog.)

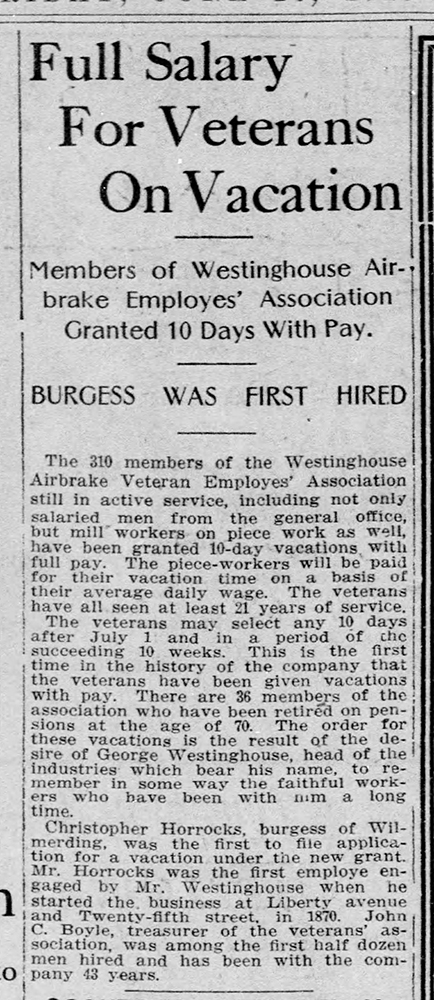

Other employers began experimenting with true paid vacations, initially handed out as bonuses or rewards for longstanding service. In 1913, for the first time Westinghouse announced that more than 300 members of the Westinghouse Airbrake Veteran Employees Association would be granted 10-day vacations with pay. “Veterans” had served the company for at least 21 years.[2]

By the late 1920s, large national companies such as General Electric announced new plans for paid vacations for all workers and more people began taking the idea seriously. The Altoona Mirror noted in 1929, “Surely America’s civilization—and its prosperity— have reached a stage where citizens should not have to work from Jan 1 to Dec 31 without any release from the daily grind.”[3]

Win some, lose some

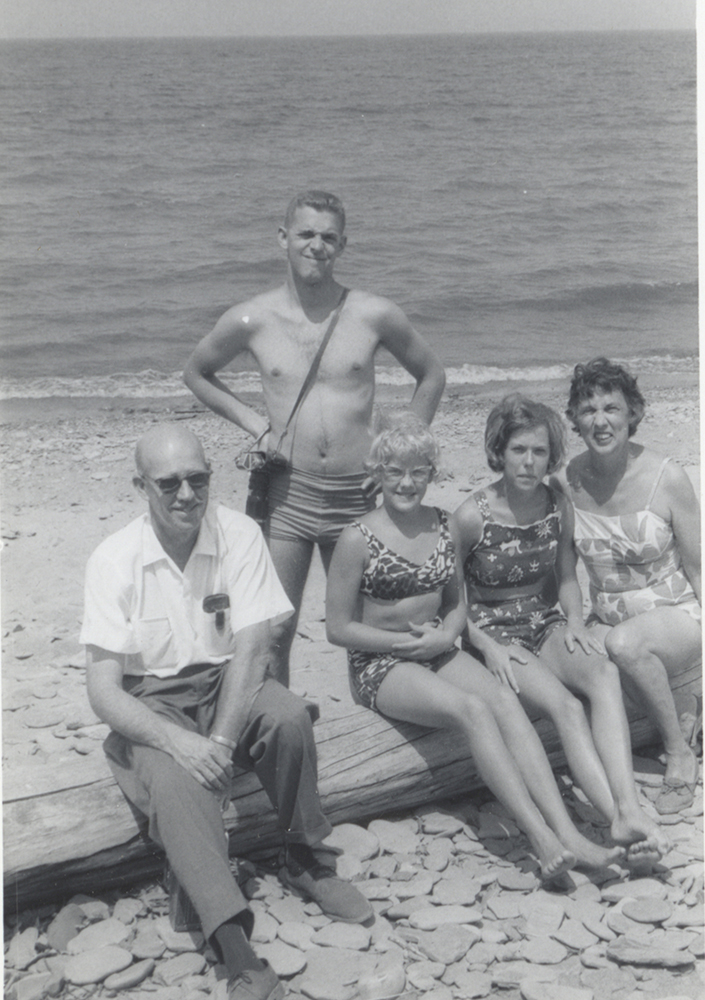

Alas, that same year ushered in the Great Depression. For a few years, Americans focused again on finding work rather than taking time off from it. But the interruption was temporary. By the late 1930s, the practice of paid vacation had gained ground both here and in Europe. It became widespread enough in post-World War II America that the “family vacation” formed an indelible part of many boomers’ childhoods from the 1950s through the 1970s.

Despite all the ground won, paid vacation remains an issue of debate in the United States. While millions of hourly and low wage workers have no paid vacation, millions of other American workers don’t take the leave they have accrued. By 2016, American workers even clocked in more average working hours than employees in Japan, that notorious nation of workaholics. Today, new generational ideas and new connectivity are changing the boundaries between “work” and “time off” once again.

Just relax

Of course, young Sean Moeller wasn’t thinking about all that back in 1985. Coming from a family with an impressive tradition of offbeat holiday creation—his grandfather, mother, father, and sister all contributed to the calendar of crazy national days—Sean was simply looking to make his mark. Given his busy schedule of helping with the dishes, cutting weeds, watering plants, and riding his bike, Sean felt that he, along with everyone else, just needed a break. “Do whatever you do to relax,” he advised, “sit in the backyard and get a suntan or lie down and watch TV.”[4] And he had never even heard of binge-watching on Netflix.

So, go ahead and relax, Pittsburgh. Follow young Sean’s advice. You deserve it.

[1] Monson, Valerie. “Relax – 9-year-old boy declares day of rest for loafers,” The Des Moines Register, August 15, 1985.

[2] “Full salary for veterans on vacation,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 20, 1913.

[3] “Finds paid vacations for workers bring big results,” Altoona Mirror, May 29, 1929.

[4] Monson, “Relax,” Des Moines Register, 1985.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.