Read the full article about Dr. Alice Bennett and the Johnstown Flood by Kenneth J. Weiss, M.D. in the Fall 2017 issue of Western Pennsylvania History.

The 40th annual meeting of the Pennsylvania Medical Society was scheduled at the Bijou Theatre in Pittsburgh to begin on June 4, 1889.[1] Dr. Alice Bennett, president-elect of the Montgomery County contingent and an asylum physician, had made the 300-mile trip from Norristown, near Philadelphia. The meeting, however, was quickly adjourned — it was too difficult to conduct business when a tragedy of enormous medical proportions was unfolding just a short distance away.

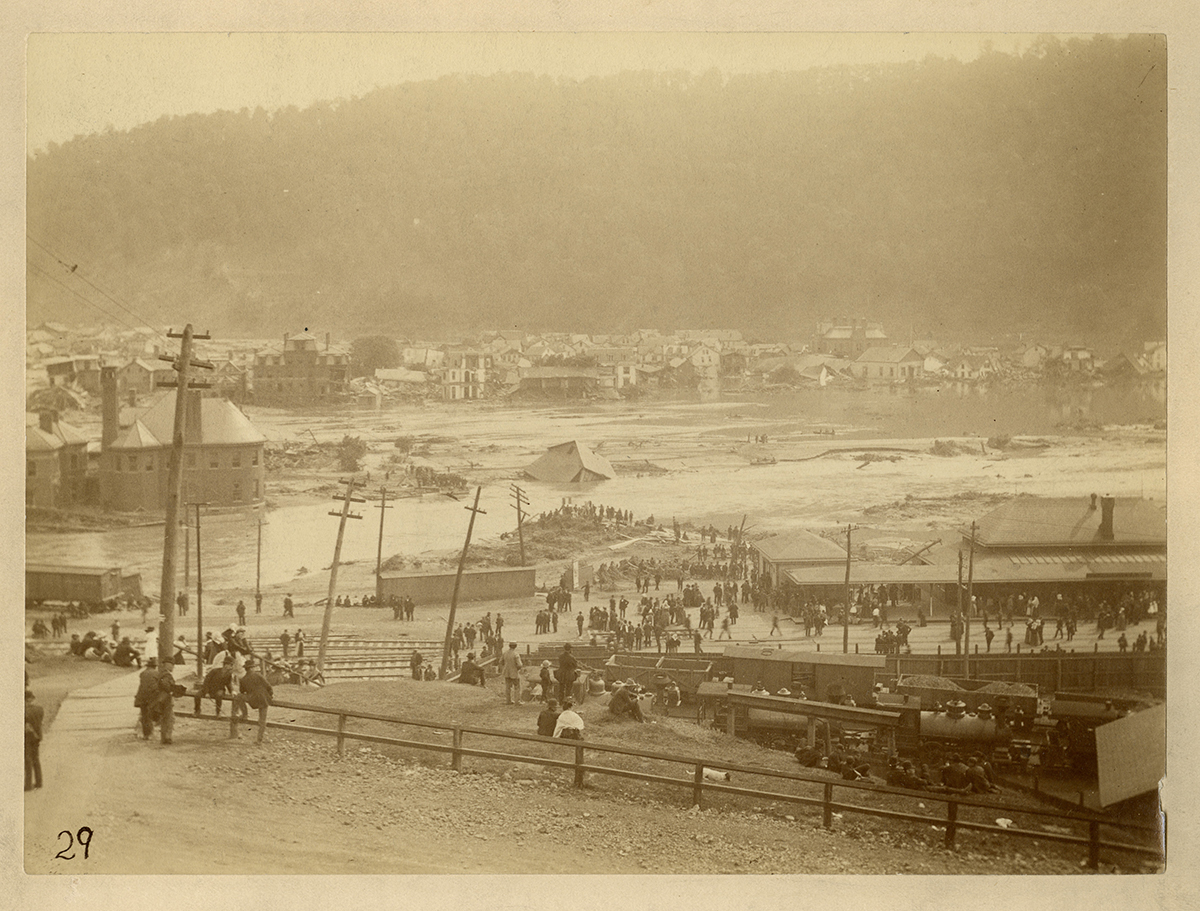

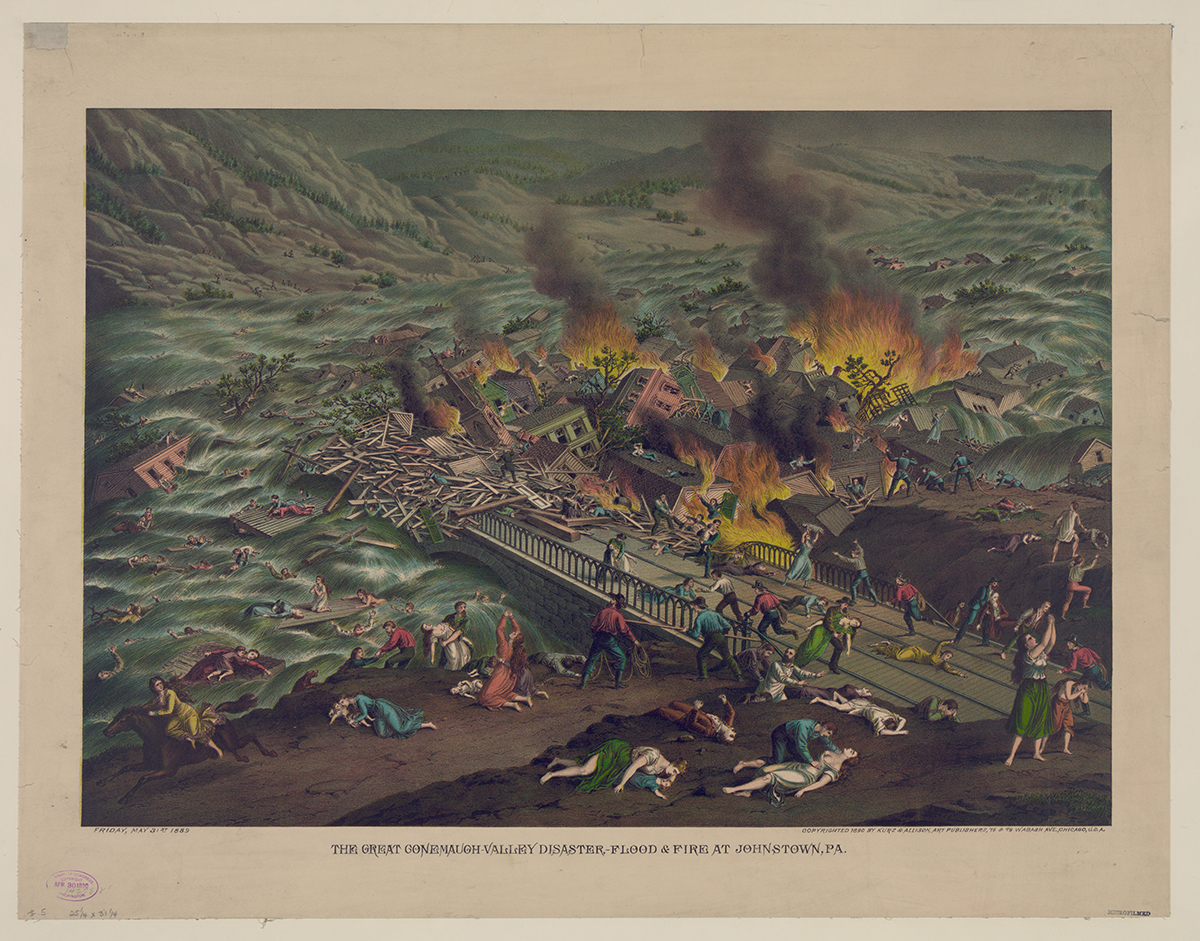

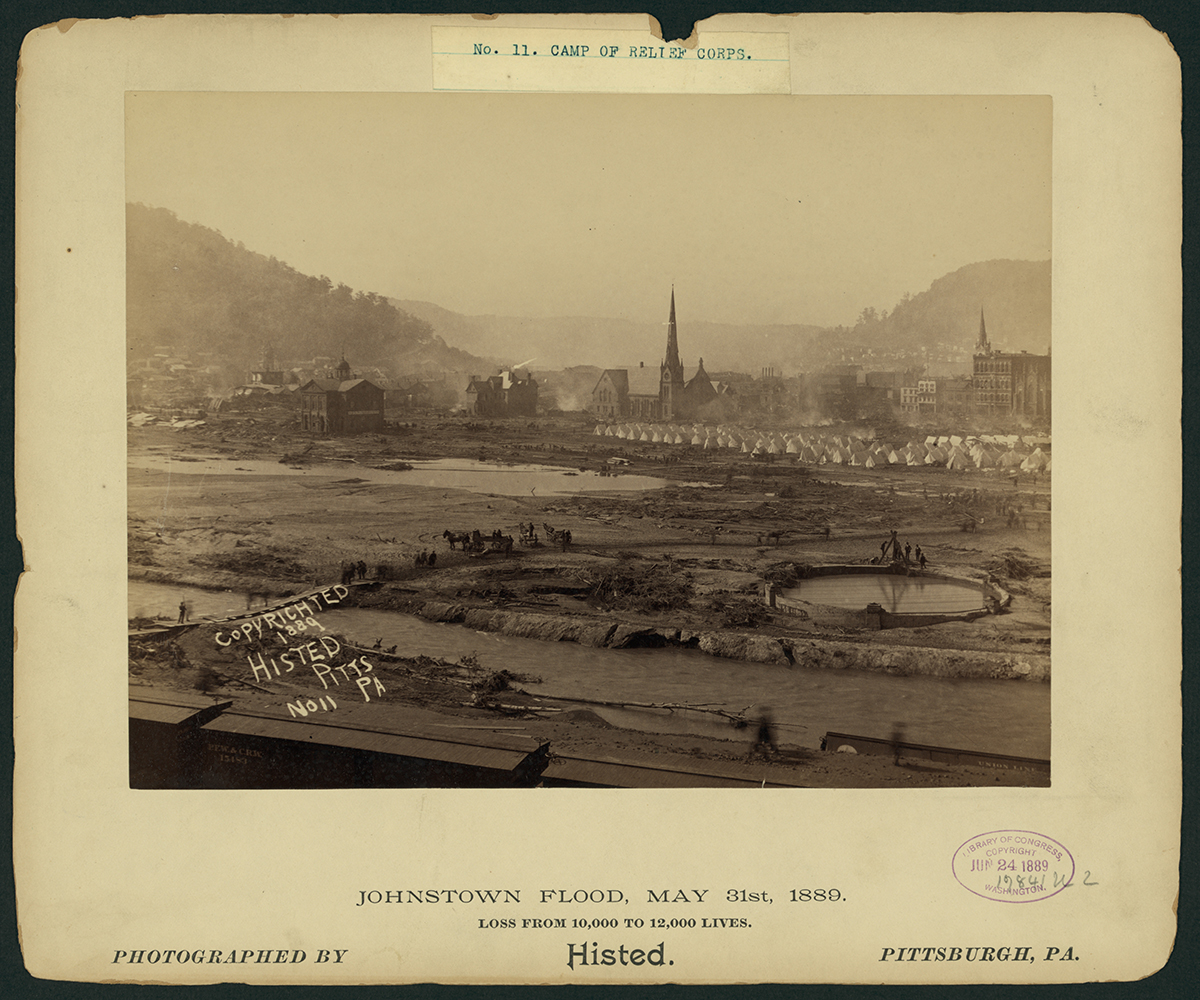

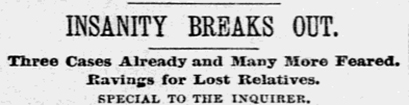

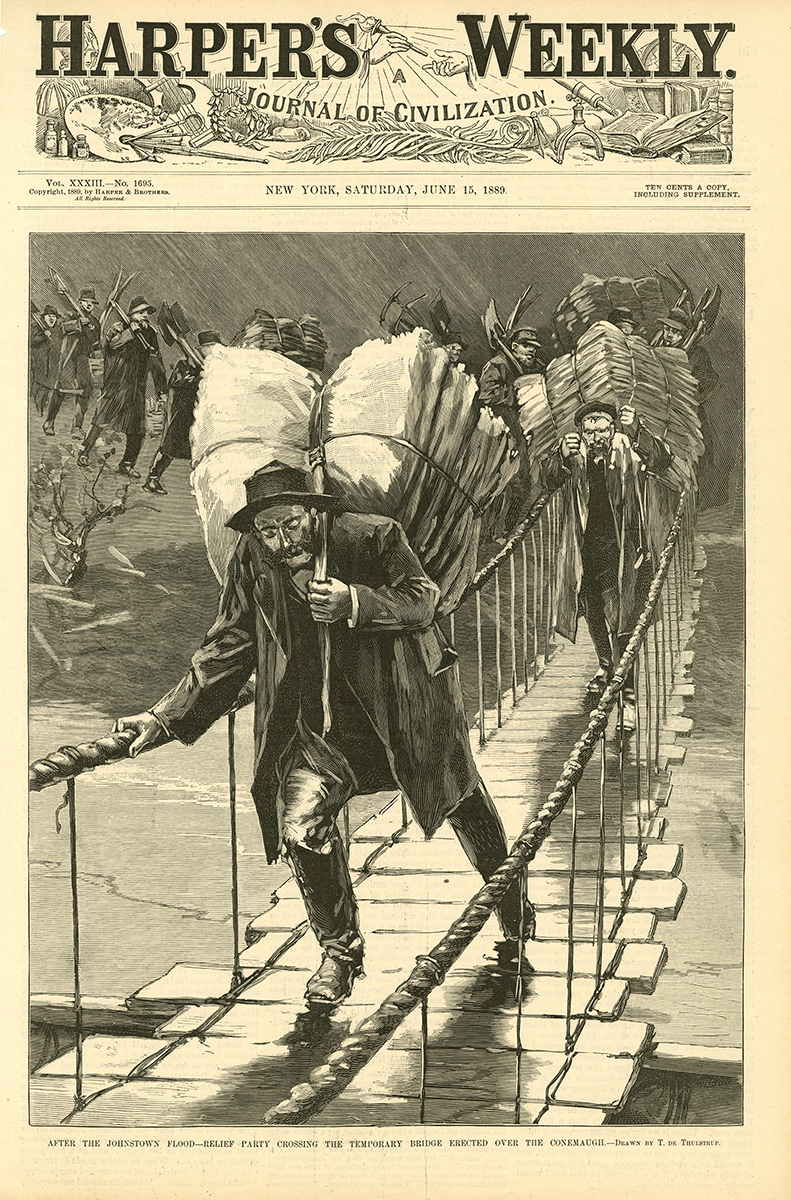

A few days earlier, the South Fork Dam holding back the Little Conemaugh River at Lake Conemaugh[2] above Johnstown had given way, plunging towns into destruction and chaos, and killing 2,200 people. Travel to the Medical Society meeting itself had been severely impeded by the destruction of rail lines. The disaster was accompanied by both psychic trauma and an immense outpouring of resources. The medical and humanitarian responses to it were instantaneous, substantial, and sustained. Dr. Bennett travelled to Johnstown looking to aid victims of psychic trauma, but she stayed only a few days; while there were many people in a state of shock, what she had predicted—an epidemic of insanity—was not to be found.

By the time of the flood, Dr. Bennett had become the first woman to be in charge of a psychiatric hospital. Born in 1851, she grew up in Wrentham, Massachusetts, graduating in 1876 from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Afterwards she dispensed care to poor residents of Philadelphia while studying anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania and teaching anatomy at Woman’s Medical. In 1880, she became the first woman to receive the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania, with her sights likely set on a quiet career in medical anatomy.[3]

Her career took an unexpected turn when a committee, looking to employ female physicians in “insane” asylums, offered her a position at a new facility in Norristown. Dr. Bennett came from the State Hospital for the Insane for the South-Eastern District of Pennsylvania (now Norristown State Hospital). Her domain was a female facility; a connected male hospital was overseen by Dr. Robert Chase. Thus, her steep learning curve in psychiatry began in 1880

Her chief innovation was abolishing restraints such as straitjackets or chains and introducing occupational therapy such as music, painting, and handicrafts. Other hospitals for the mentally ill adopted her practices, giving her recognition in the field, so that in 1889, she found herself a delegate to the Medical Society meeting in Pittsburgh. On June 7, Dr. Bennett became a self-motivated psychiatric responder.

Although Dr. Bennett had predicted that there would be widespread insanity in Johnstown, her prognostication was not realized, at least not in current-day terms. The Committee on Lunacy of the Pennsylvania Board of Charities reported a total of 15 persons who had episodes of “insanity” due to the disaster at Johnstown, which is extremely low compared to the scope of the disaster.

A year after the flood, when the Medical Society reconvened its 40th session in Pittsburgh, Dr. Bennett delivered the psychiatry lecture. [4] She had just become the first female president of a county medical society, for Montgomery County, home to Norristown. Though Johnstown undoubtedly loomed large at the Pittsburgh gathering, and was likely a defining moment to many in attendance, she did not discuss the effects of the 1889 disaster. Whether deemed insignificant, or just not recognized, the psychiatric toll on Johnstown was not to be her topic, despite her first-hand knowledge. Rather, Dr. Bennett focused on the mental effects of kidney disease, replete with 60 case studies.

[1] Atkinson W.B., Minutes of the Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, June 1889, in Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania, at Its Fortieth Annual Session, Held at Pittsburg, 1889-1890, Volume XXI (Philadelphia: Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania, 1890), p. 1.

[2] Christie, R.D., “The Johnstown Flood,” Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, 1971, p. 198–210. Lake Conemaugh was formerly the South Fork Reservoir, started in 1840. For more information, see the Johnstown Area Heritage Association, online.

[3] For more on Dr. Bennett, see her biography.

[4] Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania, at Its Fortieth Annual Session, Held at Pittsburg, 1889-1890, Volume XXI (Philadelphia: Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania, 1890). The meeting was held June 10, 1890.

Edited by Julia Snyder, Publications intern at the History Center.