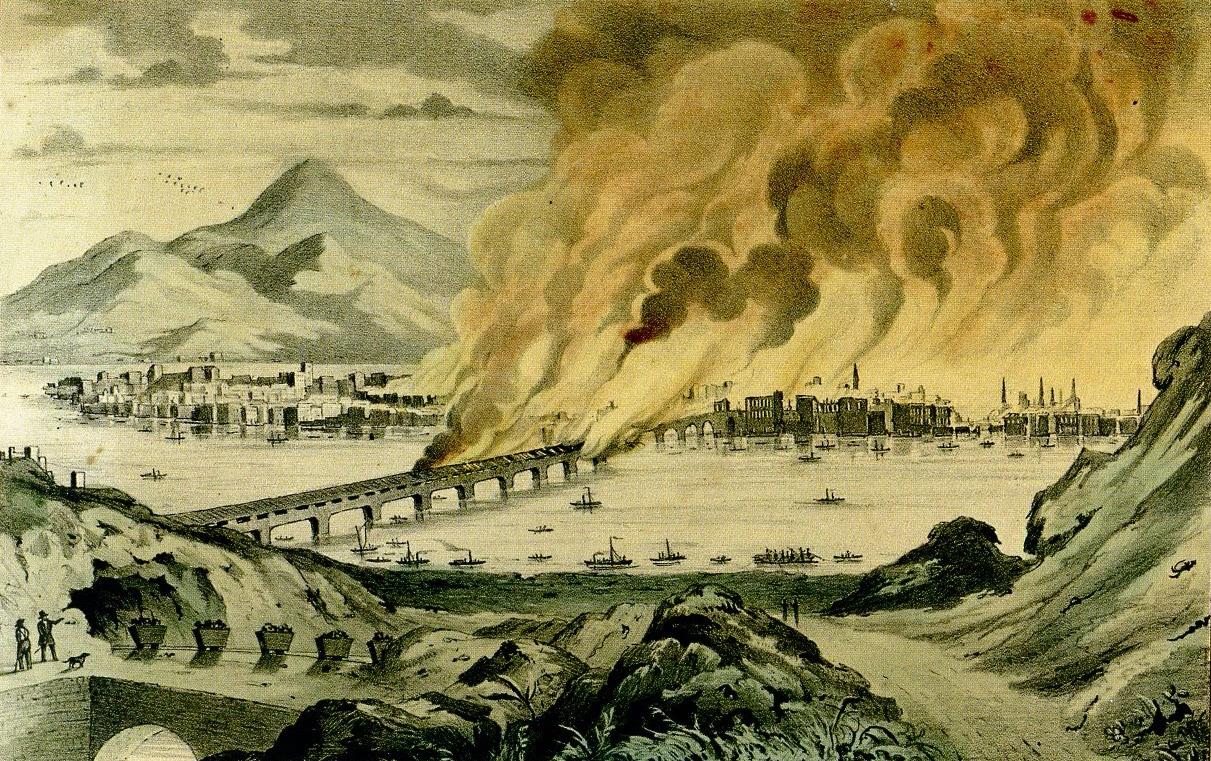

The simple china plates are among the most evocative artifacts in the History Center collection. Their surfaces streaked by singe marks from the burning straw in which they were packed, the plates testify to the impact of Pittsburgh’s Great Fire of April 1845. (Read this blog post for the story of the fire.) The catastrophe lingered in public imagination, and it even spawned one of Pittsburgh’s most famous and nearly lost spooky tales of crime and disaster, a story fitting to revisit this Halloween as the nation continues to grapple with a different calamity.

October and The Smoky City

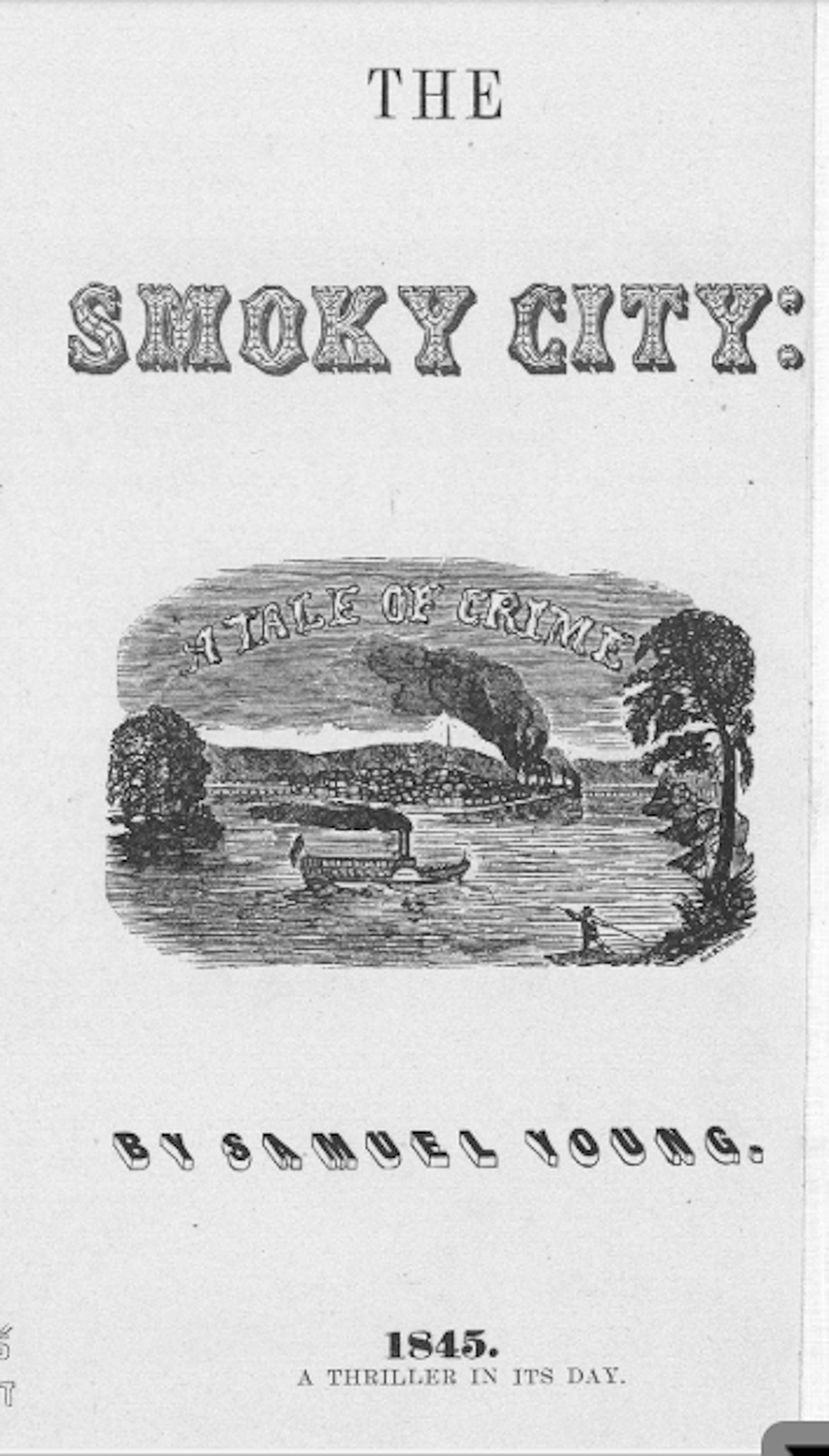

In mid-October 1845, as the city climbed out of the fire’s devastation, the Pittsburgh Post announced a new upcoming novel, “The Smoky City – A Tale of Crime.” Anticipated for early December release, the book would become one of Pittsburgh’s most famous “lost” works.

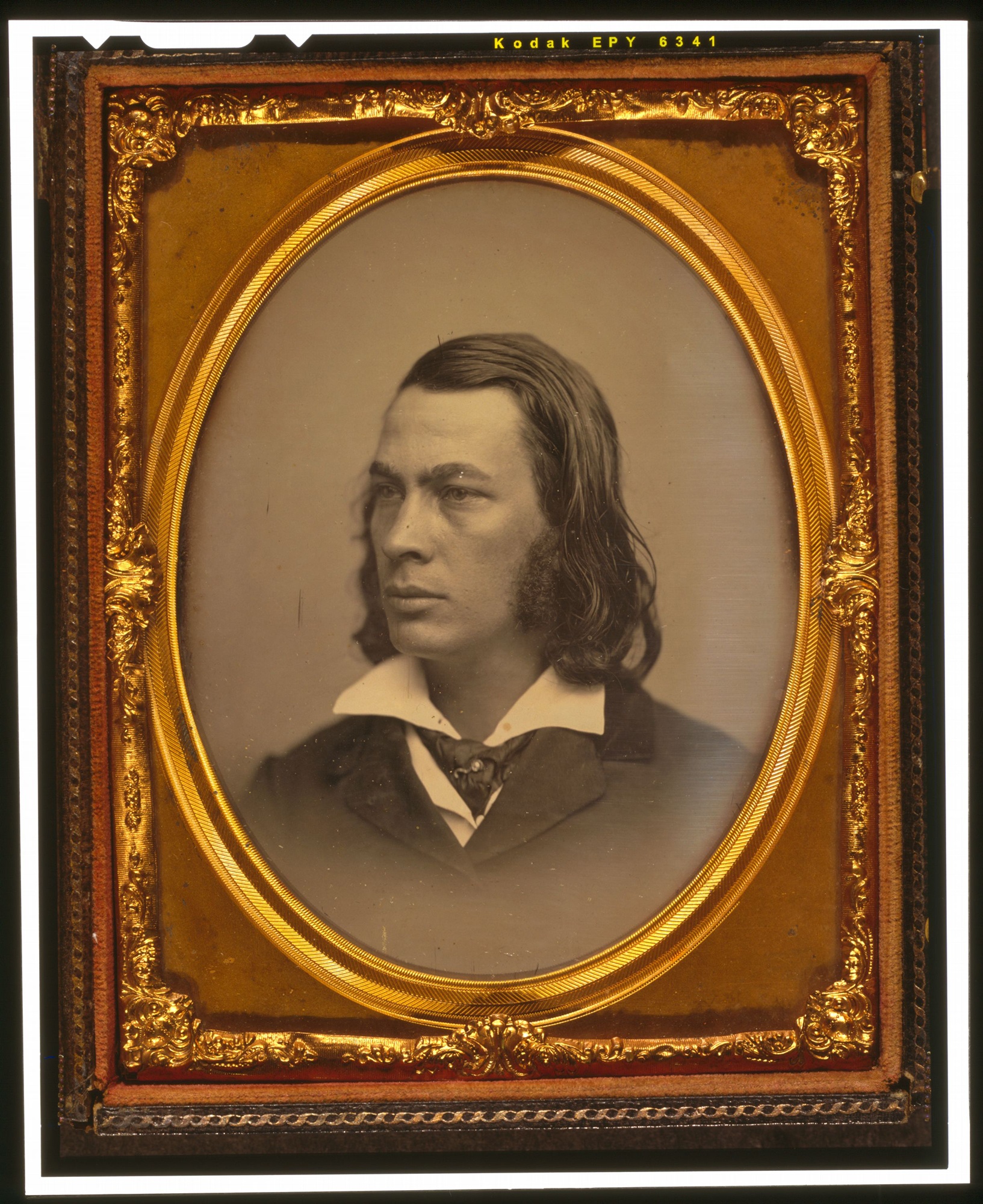

How did it connect with the Great Fire? First, its writer, an aspiring newspaper man named Sam Young, known as the “Literary Drayman” because he worked transporting barrels for commission merchants in Pittsburgh’s wholesaling industry with his dray (or cart), lost his job when flames destroyed the city’s commercial districts. Already editor of the short-lived American Eagle newspaper (also destroyed by the fire), Young had published a short story, “The Orphan and Other Tales,” by 1844. Now he was out of work. Why not devote his time to something more?

Young tapped into misfortune for inspiration and subject: “The Smoky City” used the fire as its framing device. A prophecy about the fire opened the book and apocalyptic scenes of flames engulfing Pittsburgh ended it, with murder, moral decay, and other intrigue sandwiched in between.

Pennsylvania’s “Sensation Stories”

At first glance, Young’s tale may seem a gruesome response to the city’s misfortune. But the story fit with a very popular genre of the time, one at which Pennsylvanians excelled.

“Sensation stories” and “city mysteries” emerged as part of the tabloid publishing history of the 1830s and 1840s, when lurid pamphlets featuring real crimes and trials merged with fictional depictions of nefarious activities in cities “after dark.” American authors were inspired by two serialized European works: “The Mysteries of Paris” by Eugene Sue (1842-1843) and “The Mysteries of London” by George W. M. Reynolds (1844-1845).

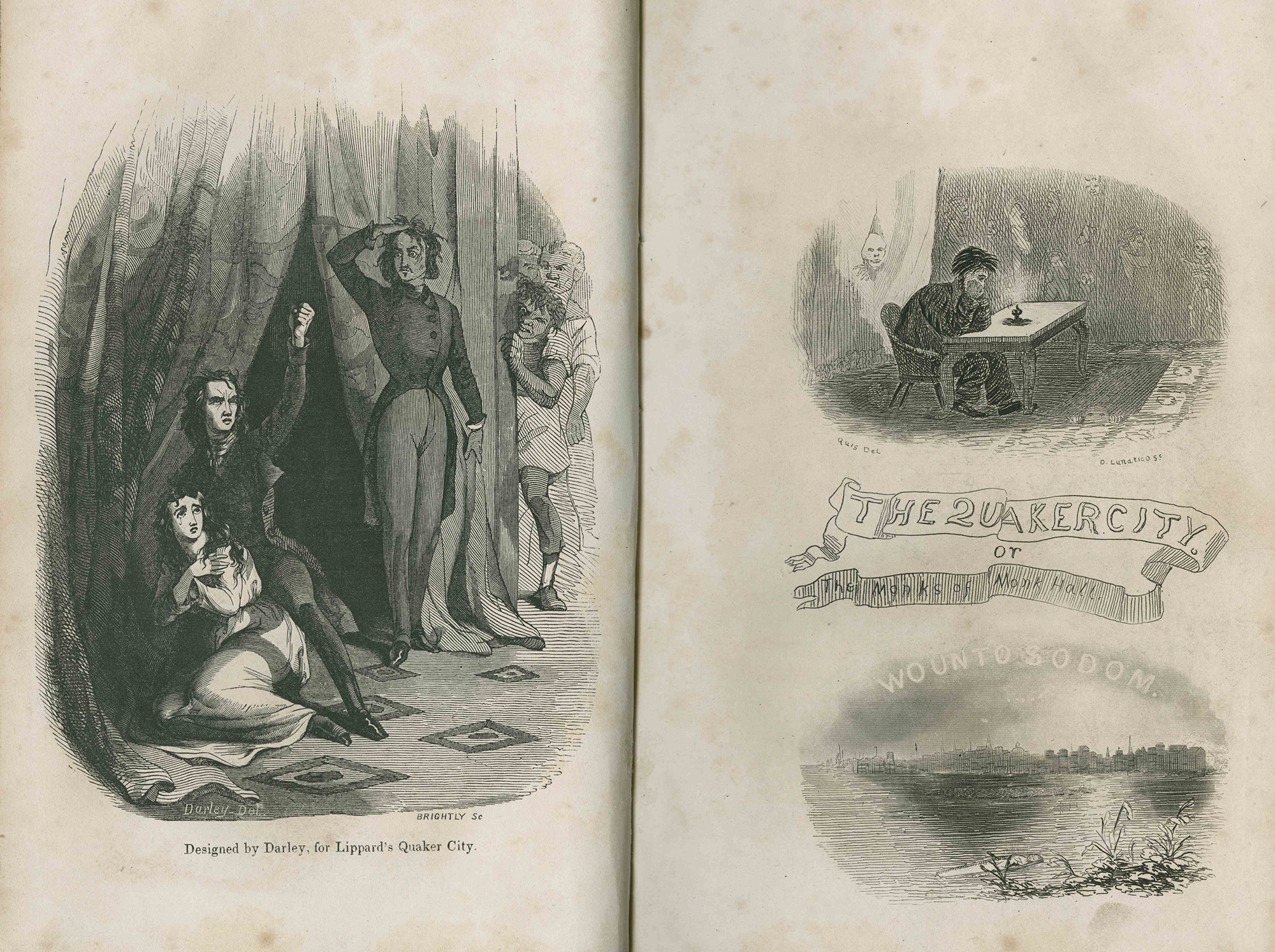

By far, the most popular American work was “The Quaker City, or the Monks of Monk Hall” (1844). Philadelphian George Lippard published the novel after a long and strange history, including a failed theatrical venture. The book, which merged abolitionism with the depiction of a Philadelphia filled with sordid crime, debauchery, and murder, was both reviled and incredibly popular, the best-selling book in the nation before Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (1852).[1] The story’s sensationalism also harked back to an earlier Philadelphia work, the great Gothic novel “Wieland” (1792) by Charles Brockden Brown, a tale set on a grand German-American estate that mixed family prophecy and the displacement of native American tribes with an atmosphere of ghostly foreboding and spontaneous human combustion. Philadelphia authors were not always known for their subtlety.

Literary Inspiration at Home

Installments of Lippard’s “Quaker City” were available at Pittsburgh booksellers by May 1845, surely timing that did not go unnoticed by Sam Young, making his way through an urban landscape barely past smoldering. Fire was a recurring motif in sensational and gothic tales. So were ruins. How could Mr. Young not be inspired?

Even more evocative, another Philadelphia-connected author’s book was also for sale in Pittsburgh by the summer of 1845. Cook’s Literary Depot on 3rd Street listed among its offerings Edgar A. Poe’s “Tales” (1845).[2] Although still not fully the household name he would become after his death, Poe enjoyed immediate success when his poem “The Raven” was published in January 1845. “Tales” included his stories “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” and “The Purloined Letter,” now considered three of the first actual “detective” stories and another reminder of the American appetite for dark and ghastly deeds set in print.

A Work Published and Lost

Was the average Pittsburgher aware of all of this? Probably not. But for an editor and aspiring author with enough poetic vision to label himself “the Literary Drayman” as he hauled barrels to and from Pittsburgh commission houses, the outburst of strange and twisted tales must have encouraged Sam Young to develop creative visions of his own.

Alas, Young was neither Edgar Allen Poe nor George Lippard. “The Smoky City” was a success at the time: Young reported that he garnered about 1,000 names for subscribers and was able to pay off his expenses and even make a profit. But his book did not end up in the canon of treasured Pittsburgh literary feats. Issued like most such works as a paperbound volume, it was not created to last, and most of the limited copies did not. By the 1940s, it was considered a lost work. More singed china plates from the fire survived than the book it inspired.

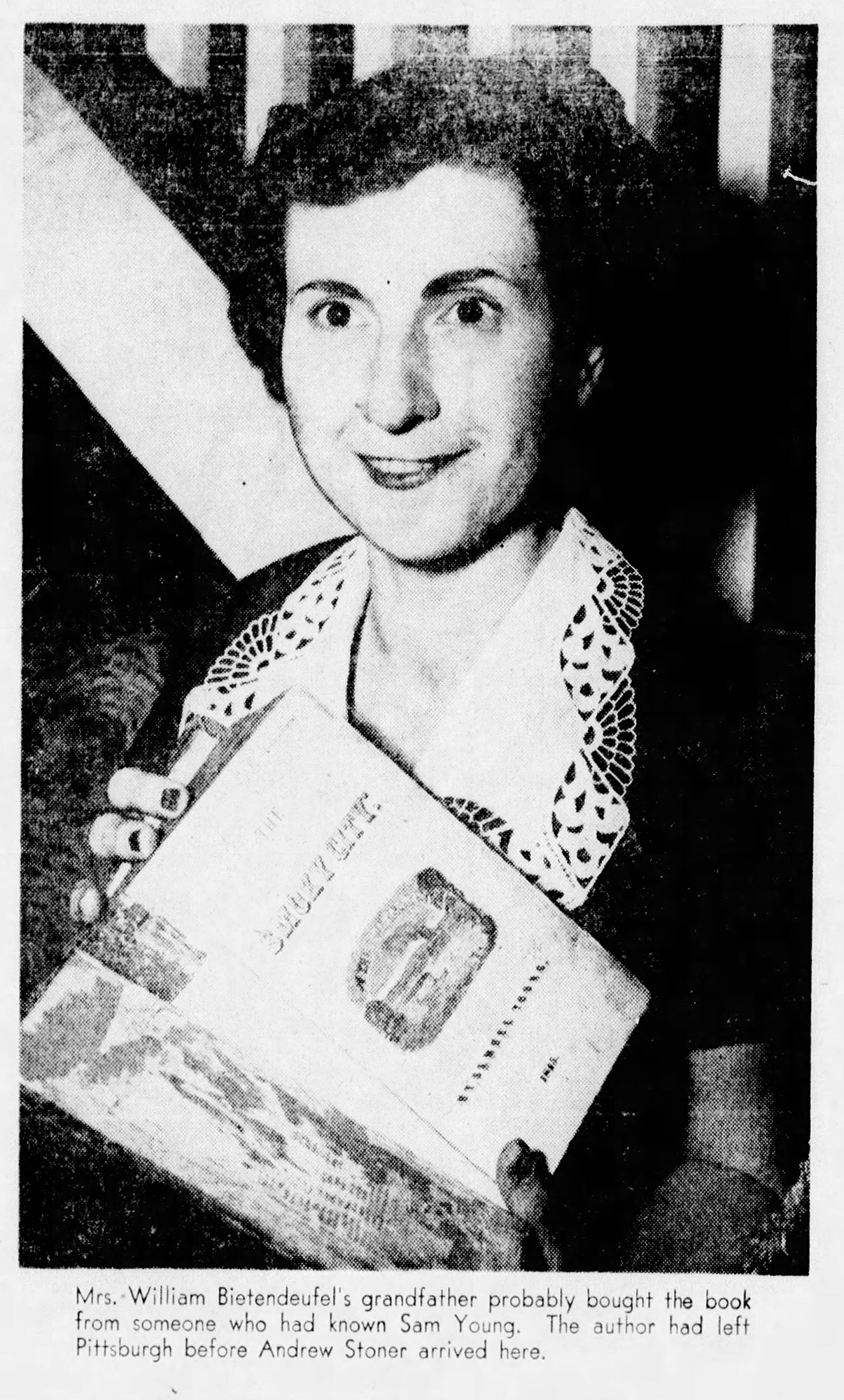

Rediscovery on Mt. Washington

Then in 1954, a woman cleaning out an attic in a home on Boggs Avenue in Mt. Washington came across Young’s tale bound with an old copy of “The Mysteries of London.” By all accounts, it was an ambitious (and very gothic) story filled with “crime, love affairs, and moralizing” that ended with the scene of a lunatic, colorfully named Davy Dumps, rejoicing over the flames.[3] Reviewers deemed the writing “amateurish,” which really wasn’t so surprising. Unfortunately, the work remains elusive, available mainly via microfilm from a few regional universities (all of which are largely inaccessible due to the pandemic). But Sam Young did follow greater pursuits. He eventually left Pittsburgh and became a newspaper editor in Pennsylvania towns such as Clarion, Franklin, and Zelienople. He also continued publishing short stories into the 1860s.

Today, as Halloween approaches and perhaps we feel the need to escape into a fictional ghost story or two, it’s useful to keep the tale of Sam Young and “The Smoky City” in mind. Perhaps it was amateurish and maybe not in completely good taste. But in the aftermath of disaster, Young found his own creative voice merging local history with broader literary strains of the time. While the book became a ghost, the man went on to make a lasting contribution in other Pennsylvania communities, surely an outcome we can find some value in today.

Watch Leslie tell this story in this History at Home video

[1] When Lippard tried to have it performed as a play at Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street Theatre, it evoked loud protests and threats of violence from the Philadelphia elite, who deemed it a violation of their private lives and immoral to boot. Of course, the outcry boosted book sales, which the author amplified through newspaper announcements. See for example “The Quaker City,” Tioga Eagle, June 11, 1845.

[2] Poe lived in Philadelphia from 1838 – 1844, considered by many scholars to be a foundational period in the development of his work.

[3] Duke Barton, “Attic Stowaway,” The Pittsburgh Press, September 19, 1954.

For Further Reading

Duke Barton, “Attic Stowaway,” The Pittsburgh Press, September 19, 1954.

Paul Joseph Erickson, “Welcome to Sodom: The Cultural Work of City-Mysteries Fiction in Antebellum America,” PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2005.

Peter Kafer, Charles Brockden Brown’s Revolution and the Birth of American Gothic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press) 2004.

“Pittsburgh’s Lost Horizon,” The Pittsburgh Press, February 22, 1953.

“The Quiet Observer,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 12, 1895. (This Post-Gazette columnist noted details about the story of the “Literary Drayman” in multiple stories, including this one, ironically dated just two days after the 50th anniversary of the Great Fire on April 10, 1895.)

Stefan Schöberlein, “Gothic Literature,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Rutgers University, 2015. Available online. This is a good overview of Philadelphia’s longstanding Gothic literary tradition and an excellent bibliography.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.