Dishing some dirt on keeping Western Pennsylvanians clean

As May 10 rolls around, it’s time to give a nod to National Clean Up Your Room Day, or as Pittsburghers might say, Redd Up Your Room Day. This annual day encourages everyone to gather the cleaning supplies and tidy up around the house. Get cleaning, Pittsburgh!

The tradition of spring cleaning dates back centuries. Winter accumulations of dirt, smoke, and soot from candles, lanterns, and fires—when every possible opening was sealed to keep out the cold—left households desperate for fresh air each spring. Then, imagine adding to that the accumulation of trash on streets and sidewalks left behind after the snow melted. Yech. By the late 1800s, many cities began undertaking their own annual cleaning, moved by new knowledge about sanitation and new expectations about the cleanliness of streets and sidewalks. “Clean” became synonymous with “progressive” and “up-to-date.”

Clean-up efforts took on special urgency in a place called the “Smoky City.” Pittsburgh residents, city officials, and private businesses all found ways to encourage greater cleanliness. Of course, some businesses also found ways to sell products related to those efforts. Cleaning campaigns ebbed and flowed through the years, intensifying after World War II, when the sustained war effort left Pittsburgh looking a bit grungy. That was a key factor in the genesis of the city’s so-called Renaissance, but it certainly wasn’t the first time that Burgh residents were called on to clean up the place they called home.

Here are four things featured in the History Center’s collections that helped area residents “redd up.”

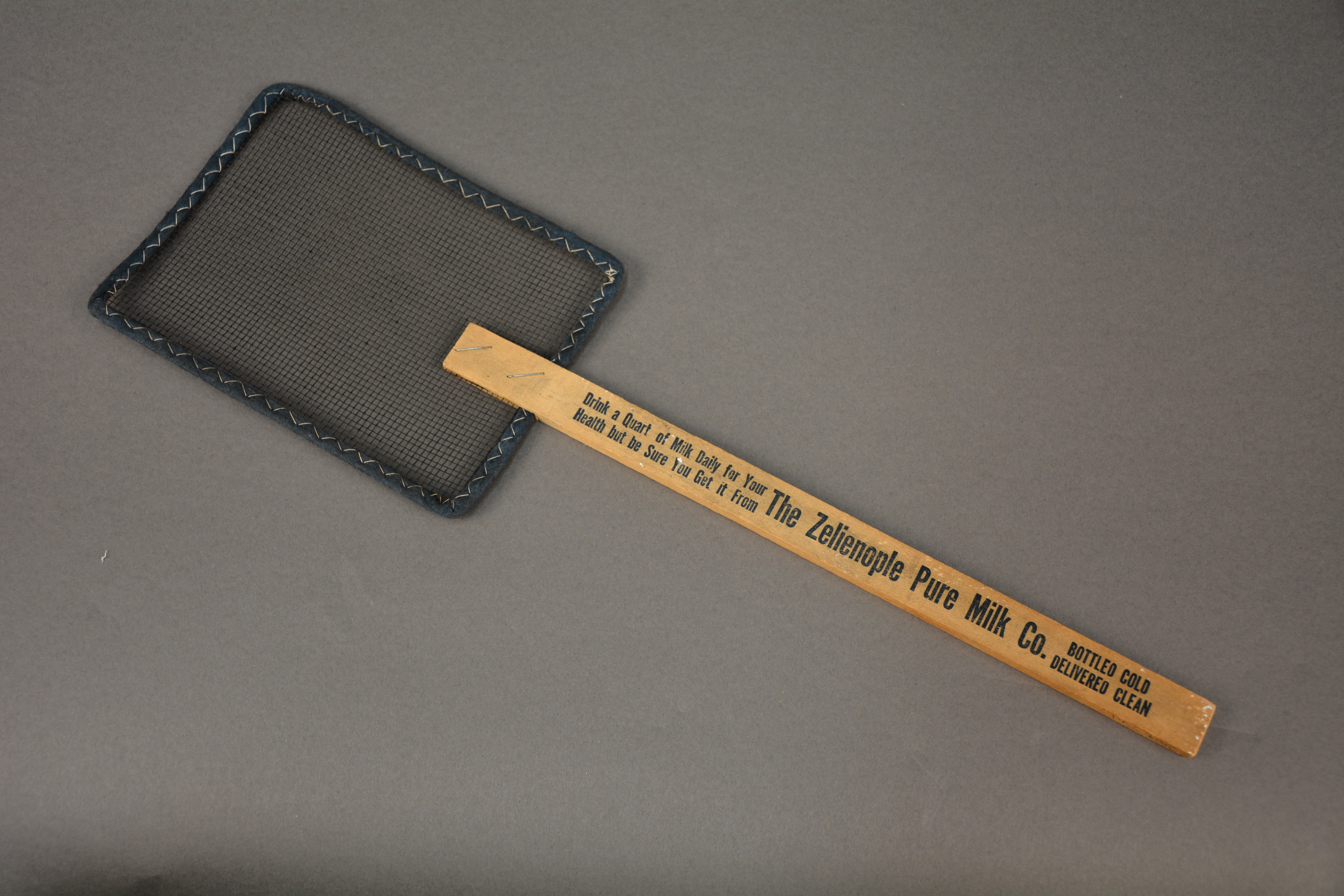

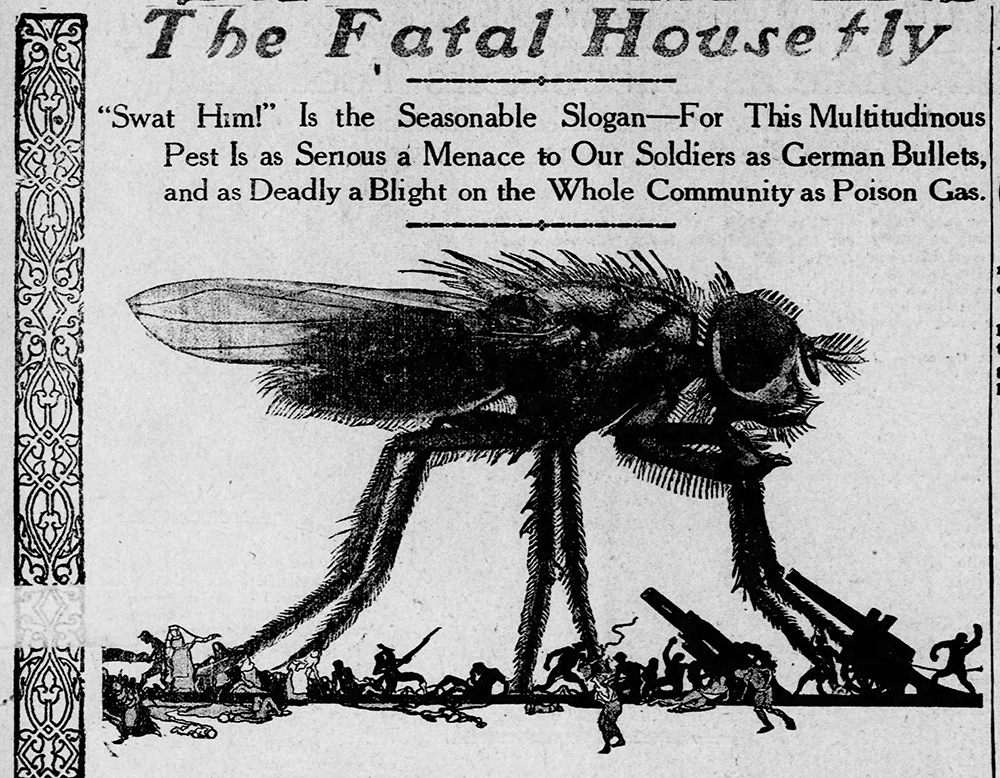

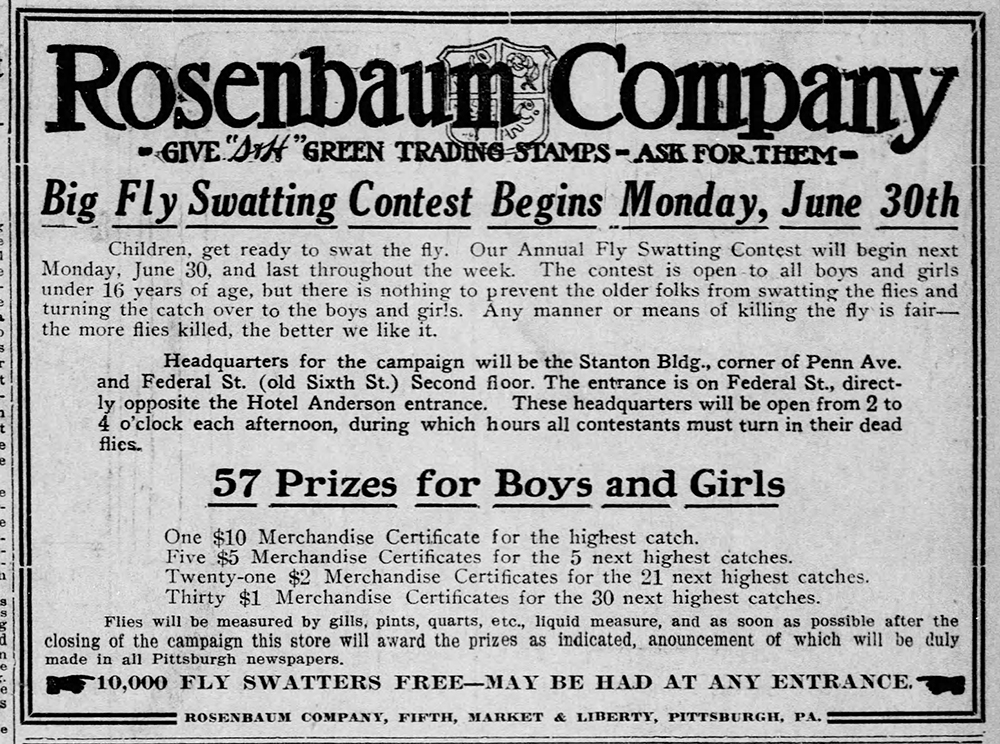

The traditional fly swatter wasn’t invented until 1906, when a Kansas Boy Scout leader took window screen mesh and nailed it to a yard stick. He called it a “fly bat,” but the name “swatter” soon stuck. By the 1910s, communities across America regularly engaged in “Swat the Fly!” campaigns to combat the spread of disease. Local companies eagerly joined these efforts. Newspapers featured dramatic illustrations of “fly combat.” Department stores such as Rosenbaum’s in Pittsburgh gave away thousands of fly swatters and sponsored fly swatting contests. The contest rules were pretty loose. Noted Rosenbaum’s in 1913: “The contest is open to all boys and girls under 16 years of age . . . . But there is nothing to prevent the older folks from swatting flies and turning the catch over to the boys and girls. Any manner or means of killing the fly is fair—the more flies killed, the better we like it.”

No, messy roommates and lazy housekeepers were not thrown in jail. This badge for the Pittsburgh Sanitary Police reflects the city’s growing awareness of how cleanliness impacted the well-being of the community. Calls for a sanitary policing agency started as early as 1865, when The Pittsburgh Daily Commercial lambasted city government for filthy streets and alleys filled with “pestilential vapors.” By the 1910s, the Sanitary Police operated as part of the Bureau of Sanitation within Pittsburgh’s Department of Public Health. Officers spread out through 25 city districts and inspected alleys, streets, privies, vacant lots, and other locations where garbage accumulated. This army of inspectors reported their findings back to a central office each day, where notices about violations were generated and sent to property owners.

There’s no gray area here. The name and graphic on this box emphasize exactly what local households were trying to fight with these laundry flakes. Keeping white laundry items clean (much less actually white) was a never-ending battle in a city whose urban landscape and social reality were defined by mills and factories. Smoky City packaging also reflected the diverse nature of the population that brought the city’s industries to life: instructions for use were provided in English, Italian, German, and Slavic (probably Czech).

Of all the programs that encouraged Pittsburghers to clean up over the years, perhaps none was as enthusiastic as Pa Pitt’s Partners, founded in 1947. Emerging out of the industrial aftermath of World War II, Pa Pitt’s Partners was a city-wide effort backed by 150 local business leaders. Opening with the slogan “Team Up for Clean Up!,” the group operated out of an old Quonset hut on Grant street. Through the late 1940s and early 1950s, Pa Pitt’s Partners worked with civic clubs, school groups, women’s clubs, and anyone else who was willing to help pick up trash and refuse, repair and paint old buildings, clean sidewalks, sweep out vacant lots, and beautify the city with new gardens. These campaigns were often promoted by the figure of Pa Pitt himself, complete in colonial garb.

Come on Pittsburgh, tell us: what inspires you to redd up?

Want to know more?

“The Invention of the Fly Swatter,” 2007. Screening for Health, Insects and Disease Prevention. University of Virginia. Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library.

Martin V. Melosi. “The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present.” Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

“Pittsburgh’s Trash History.” 2014. The Diggs. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

“Sanitary Pittsburgh Thirty-Two Years Ago and Now,” The Pittsburgh Daily Commercial, Wednesday, Nov. 22, 1865.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.