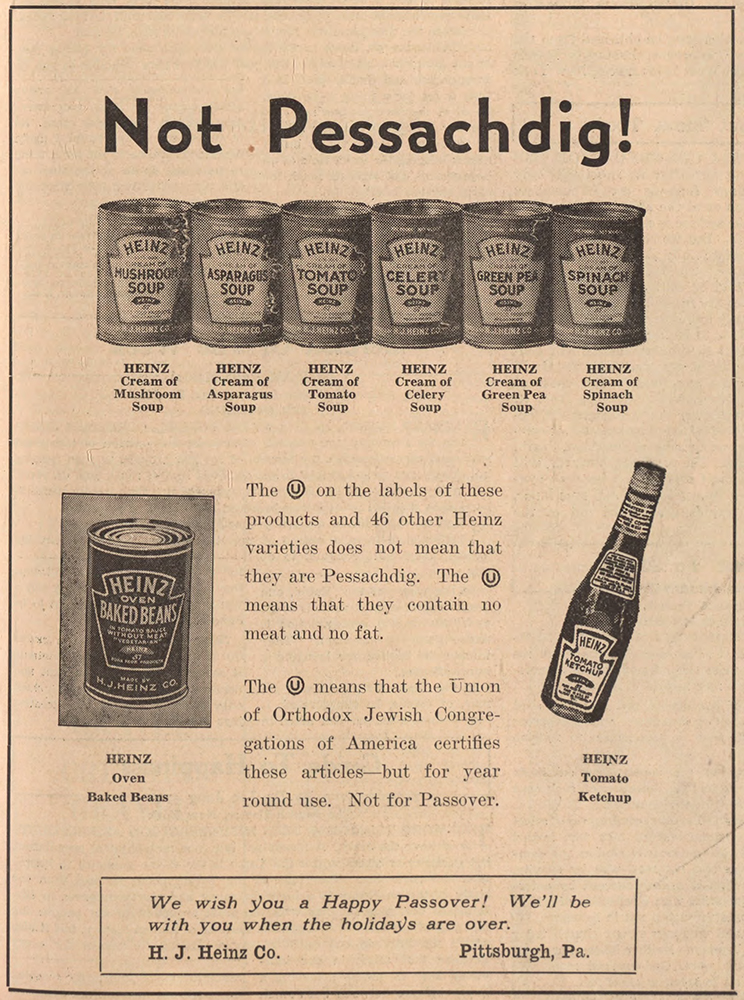

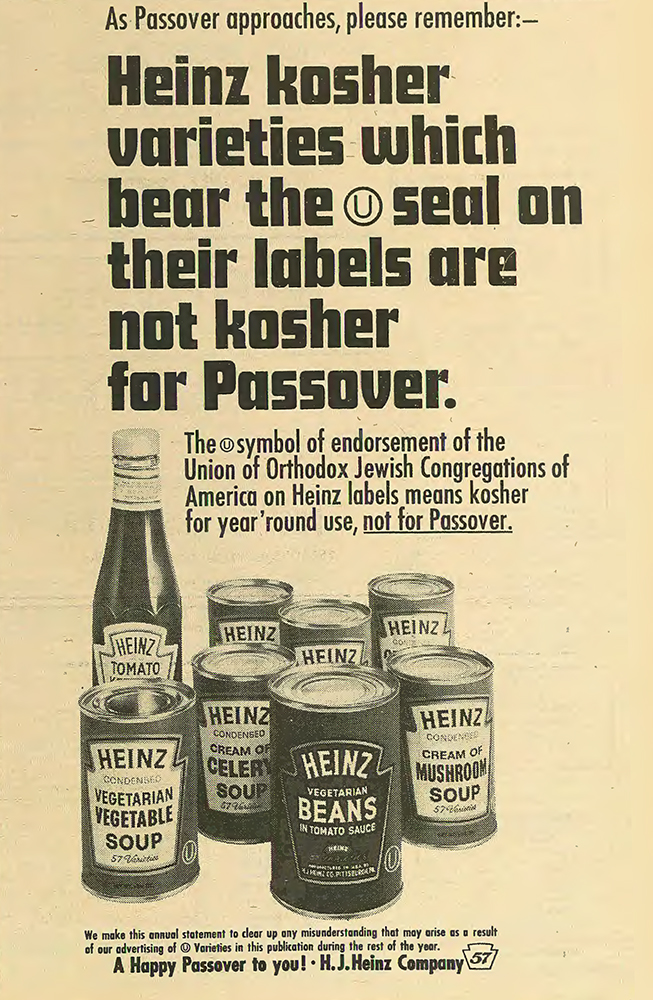

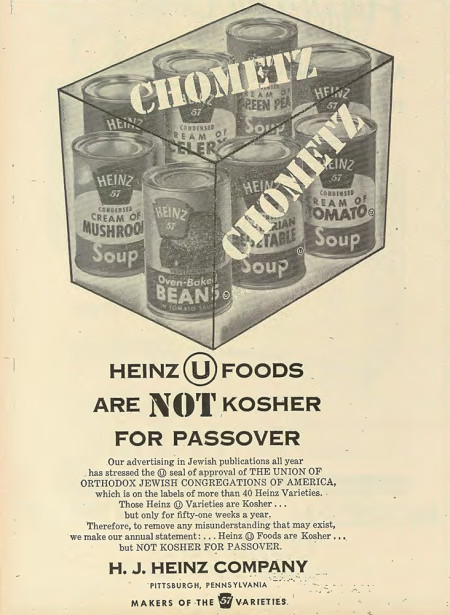

Every spring, readers paging through the mid-century Pittsburgh Jewish press could expect to see an advertisement different from all other advertisements:

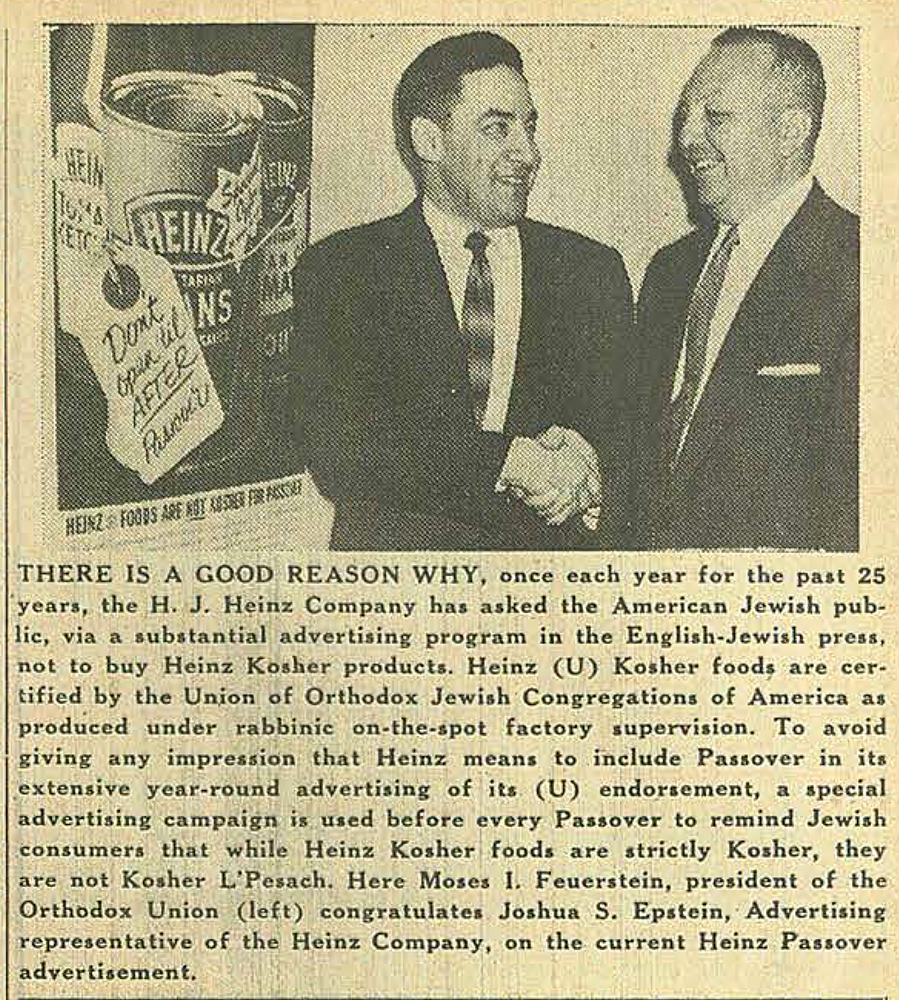

This statement from the H.J. Heinz Company stands in striking contrast to the advertisements typically run in the Jewish Criterion. Its visual language is better suited for a Civil Defense announcement than a soup ad. “CHOMETZ! CHOMETZ!” it warns the reader, using the Hebrew word for the category of foods forbidden on Passover. This ad and other versions of it across the years demonstrates the H.J. Heinz Company’s sensitivity to its religiously-observant Jewish customers’ dietary needs. It is not often that a corporation purchases an ad urging customers not to buy its product. Heinz’s annual pre-Passover statement is emblematic of the long and unique connection between the company and the Jewish community in Pittsburgh and beyond.

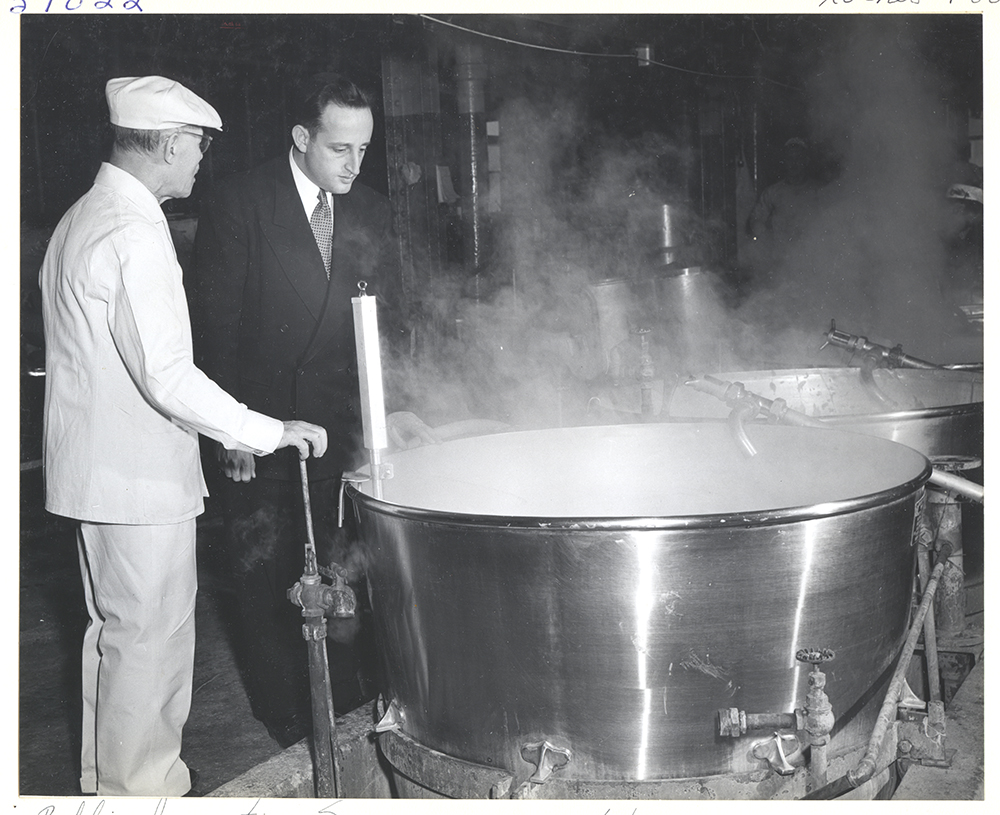

You may not have noticed, but much of the packaged food you buy is emblazoned with a small “U” nested within an “O.” The Ⓤ symbol is the insignia of the Orthodox Union rabbinical council and any product that carries the OU’s mark has been approved by the council as kosher. According to the Orthodox Union, today between one-third and one-half of the food sold in typical U.S. supermarkets is labeled as kosher.[1] However, this was not always the case. The corruption and lack of transparency that characterized much of the food industry at the dawn of the Progressive Era extended to the world of kosher certification. Consumers had little guarantee that the packaged and canned food they ate contained what manufacturers said it did. In 1924, the Orthodox Union (formerly the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations) established an agency to send supervising rabbis, known as mashgiachs, to inspect factories and certify products. By comparison, it was not until 1938’s passage of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that the federal government had the authority to carry out factory inspections of its own.[2]

For a company that fought for 1906’s foundational Food and Drug Act and boasted of compliance with “all laws throughout the world” on its labels, certification from the Orthodox Union offered another way for Heinz to set the standard for food purity. In 1927, the H.J. Heinz Company became the first national brand with products approved by the Orthodox Union.[3] Heinz also became the first company to tout the now ubiquitous Ⓤ on many of its labels. In fact, the symbol’s simple, durable design was the work of a collaboration between the Orthodox Union and the H.J. Heinz Company’s art department.[4]

Not every Heinz product is kosher. Cans of pork-and-beans or split pea soup with ham do not bear the symbol of the Orthodox Union. However, the number of Heinz items available to religiously-observant Jews has grown over the years – 26 in 1927, 47 in 1937, over 50 by 1942 – and remains impressive. Heinz’s year-round Jewish-targeted advertising is likewise impressive for its code-switching and familiarity with its audience. Informal descriptors like meichel (“delicacy”) and mechaya (roughly, “a delight”) abound and the ad below signals an understanding of the dietary laws governing the separation of dairy (“milchig”) and meat (“fleischig”) dishes.

For many Jews, the prohibition on leavened bread on Passover (“chometz”) extends to other cereal grains and legumes and necessitates a thorough cleaning of the entire house. The work required to scour all grain from Heinz’s premises for one week of kosher-for-Passover production explains why the company did not undertake to become kosher the entire year round. However, Heinz took the step of creating expensive and memorable ad campaigns warning its customers off its products during Passover. Heinz’s annual Passover statements served as an expression of and investment in the historic relationship the company enjoyed with the American Jewish community.

To learn more, check out the “Passover in Pittsburgh” digital exhibit on the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives’ Generation to Generation website, the History Center’s H.J. Heinz Company’s Digital Collection Highlights, Historic Pittsburgh’s Photographs from the H.J. Heinz Company Collection, and the Pittsburgh Jewish Newspaper Project.

David Schlitt was formerly the director of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives.

[1] Eleanor Foa Dienstag, In Good Company, (New York, N.Y.: Warner Books, 1994), p. 275.

[2] Shulamith Z. Berger, “The OU: Pioneering the Jewish Food Industry,” Jewish Action, Summer 2011, 47, accessed April 2016.

[3] Bayla Sheva Brenner, “The Super Mashgiach,” Jewish Action, Summer 2011, 46, accessed April 2016.

[4] “FDA History – Part II: The 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act,” accessed April 2016.