One weekend in our #Pixburgh: A Photographic Experience exhibit, a docent watched as two teenage sisters posed for each other. One took out her new Polaroid instant camera (they’re all the rage again, if you hadn’t heard) and snapped a picture of her sister, who was pretending to take a picture of her with an old Polaroid Land camera from our handling collection. It was a simple moment that reminds us why people continue to find picture-taking so engaging. Photos connect us in multiple ways. Both the image and the act speak across time.

Photography’s broad appeal is one of the things that makes it such an indelible part of modern society. It’s also something that cultural critics on occasion repeatedly bemoaned as the technology of picture-taking opened up and crossed from the boundaries of art and science into the realm of mass-entertainment.

Of Gems and Hogs

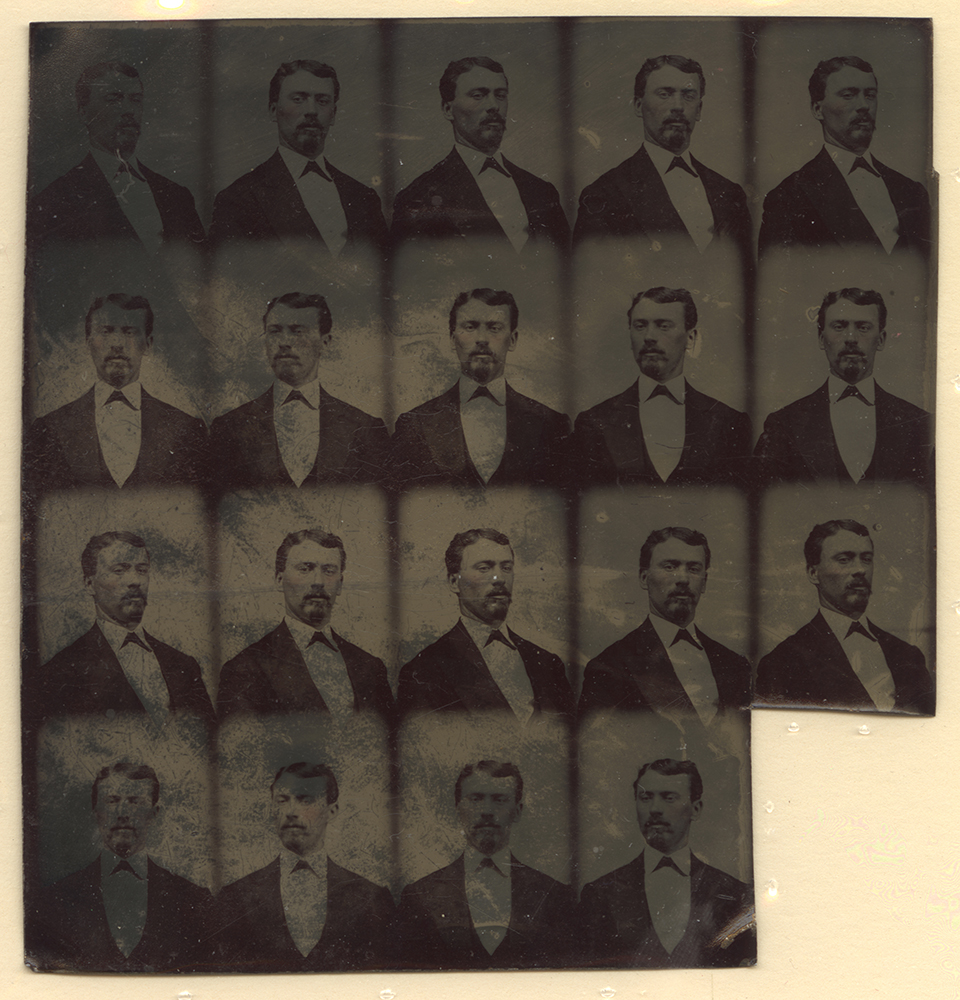

An artifact in #Pixburgh illustrates this well. In the exhibit’s opening gallery, a small display case holds a sheet of iron with 19 tiny images printed on it, a set of “gem” tintype portraits on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. It’s a modest item and easy to miss unless you are looking for it. You would never guess that the technology used to create these little images generated a frenzy of handwringing and lamentation from some cultural critics in the 19th century.

The tintype, a direct positive print on iron (not tin), was created by a camera that could generate multiple images at a time. Its rising popularity by the 1860s helped displace the daguerreotype, the first widely available photographic technology in America.

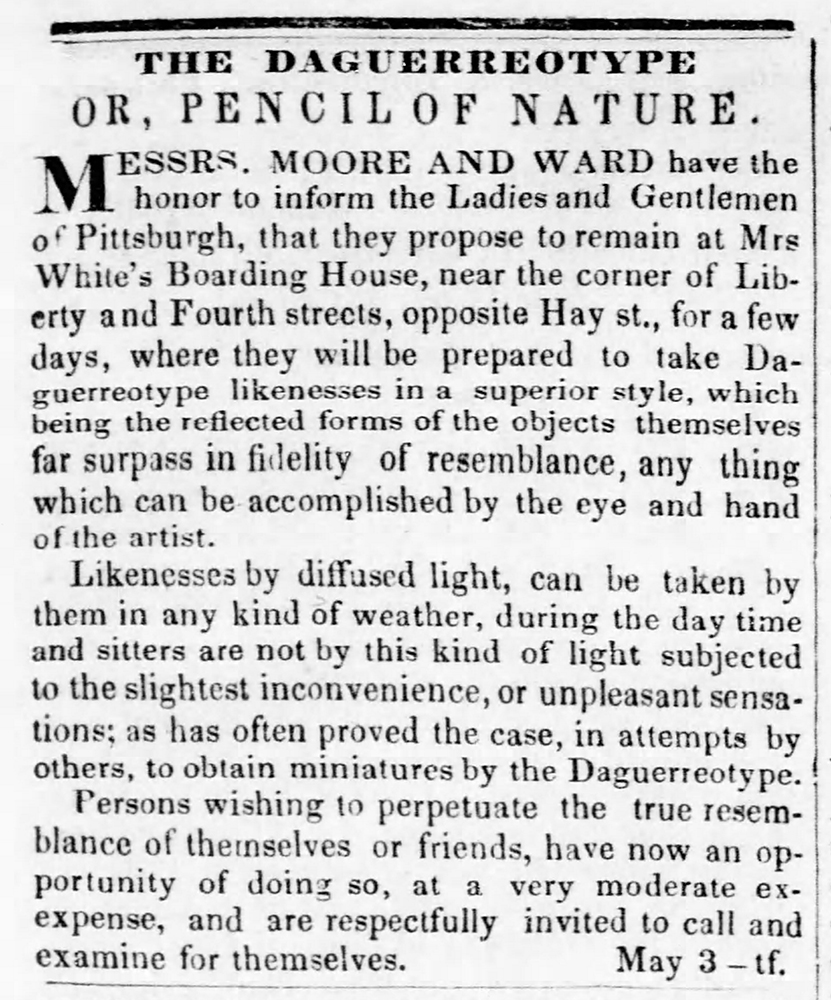

When early daguerreotypes reached the U.S. in 1839, newspapers lauded them as miraculous. The New York Observer exclaimed, “With what interest shall we visit the gallery of portraits of distinguished men of all countries, drawn, not with man’s feeble, false, and flattering pencil, but with the power and truth of light from heaven!” (April 20, 1839). High praise indeed. To some, daguerreotypes looked like jewels. The image – one image, that’s all you got – was printed on a silvered copper surface that glittered like a mirror. Mounted under glass in a small cushioned case, it felt like a miniature family bible or small treasure chest. Most early daguerreotype portraits followed the tradition of painted portraits – sitters look out with serious expressions. The idea of “mugging” for the camera was decades away. While daguerreotypes were more accessible than an artist’s painted image, something of the decorum of that earlier experience remained.

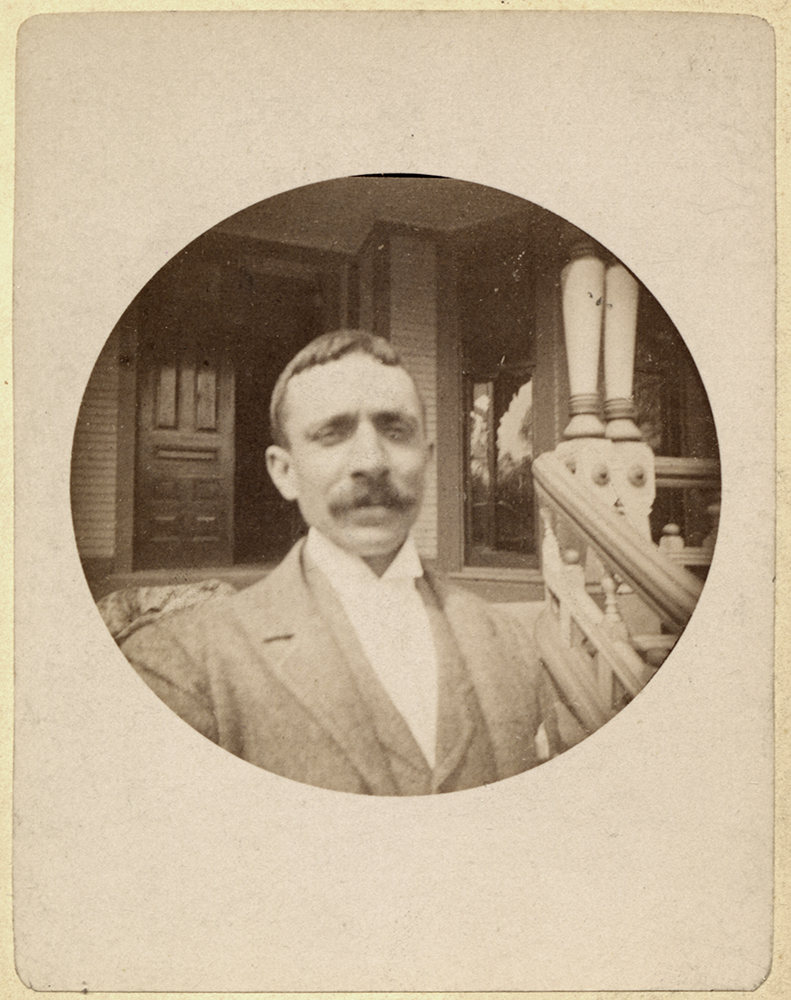

The tintype was different. So easy that nearly anyone could learn the technique, so portable that a shop could be set up almost anywhere (as long as there was a source of natural light), and so inexpensive that nearly anyone could afford them, tintypes appealed to the mass population of Americans who found even the daguerreotype’s cost beyond reach. Now, for a small fee, you could purchase multiple images to share with family and friends. The durable little tintype became the face of the American Civil War, the most popular image exchanged by a generation that marched away expecting a skirmish of months but who wound up entangled in a brutal conflict that sprawled into years.

Tintype portraits documented factory workers, immigrants, the well-to-do and the commercial class. Critics, many of them daguerreotype specialists, complained that the new mode was so simple its practitioners placed profit above art. They hated the new images, hated the technology that created them. Hated that they saw them everywhere. They charged that the tintype’s lesser qualities were marketed mainly to the “poor and illiterate.” Trying to teach such people the merits of aesthetic beauty (presumably, the merits of the daguerreotype), wrote one disgruntled photographer, “was like throwing beautiful gems and lovely pearls in the midst of a drove of brewery hogs.” Ouch.

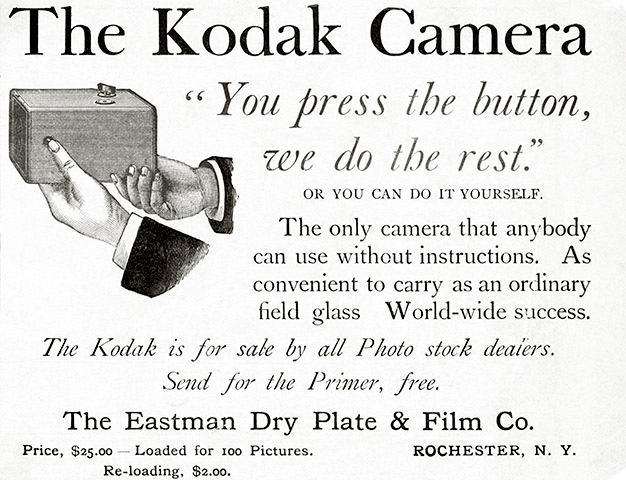

Alas, technology marches on. We can only imagine what such critics would have made of later inventions. George Eastman put the actual camera into people’s hands with his first Kodak box camera in the 1880s, marketed by promising, “You press the button, we do the rest.” So much for the difficulty of high art.

Meanwhile, stereographs, a 19th century form of 3-D photographic technology that used a special viewer and cards with two nearly identical images mounted on them, enjoyed great popularity between 1870 and 1920. Stereograph cards featured a dizzying array of topics, from scenic views of Niagara Falls and disasters such as Pittsburgh’s 1877 Railroad strike riots to lampoons of domestic life. Again, art and mass culture diverged. Intellectuals envisioned “stereograph museums” celebrating the world’s great artistic and cultural achievements. Regular citizens amused themselves with less edifying topics such as “Mr. and Mrs. Turtledove’s New French Cook” – a set of cards charting the course of a husband’s ill-fated affair.

But photography’s ability to span the gulf between divergent tastes has always been part of its staying power. The same technology that can capture Pulitzer prize-winning images or freeze moments that symbolize a nation can also preserve a playful interlude with someone’s cat or a morning cup of coffee shared with Facebook friends. As a 1964 Kodak camera TV commercial once said, “Next to the pickles, it’s the most important part of a picnic.” The results might not be high art, but our world just wouldn’t be the same without it.

For more information

Colin Harding, How to Spot a Ferrotype, Also Known as a Tintype (1855 – 1940s), 2013. National Media Museum.

Karen Langberg, Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes & Tintypes: The Rise of Early Photography, 2011. Skinner Auctions.

J. Rodgers, Twenty-Three Years Under A Skylight: Or Life And Experiences Of A Photographer. Hartford, Conn., 1872.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.