August 14 marks the anniversary of the day in 1894 when astronomer and instrument maker John Brashear, along with a group of his employees, placed a small time capsule box in the cornerstone of their workshop building in Observatory Hill.

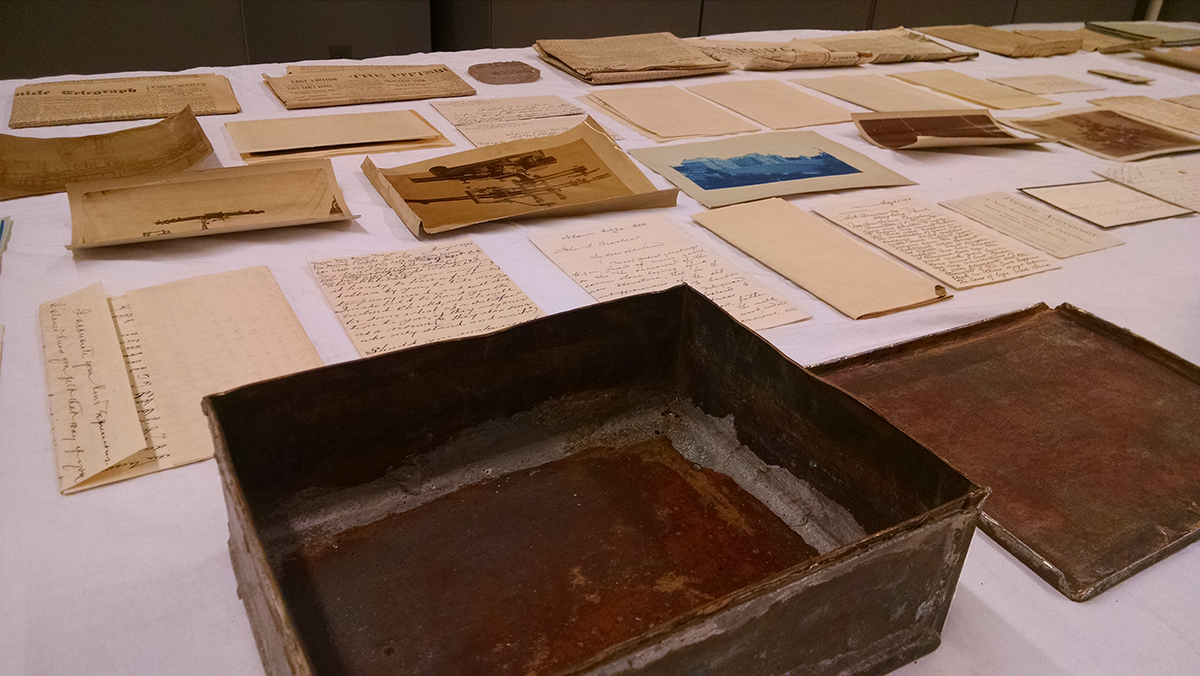

More than 120 years later, on March 24, 2015, as workers from the Jadell Minnifield Construction Company demolished the last wall of the John A. Brashear Astronomical & Physical Instrument Works at 2016 Perrysville Ave. in the North Side, that same metal box appeared in the wreckage. It contained nearly 60 documents, photos, and objects.

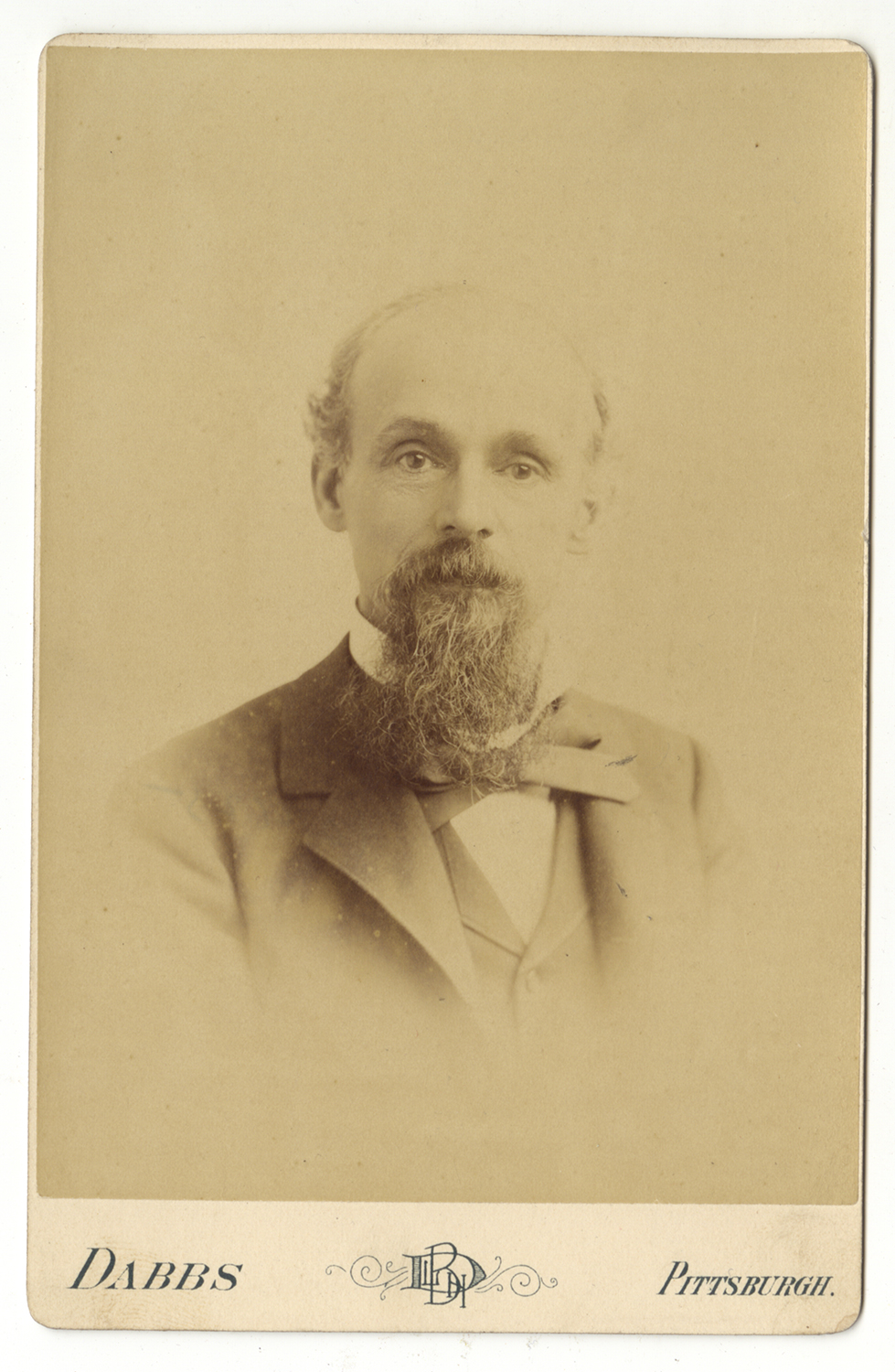

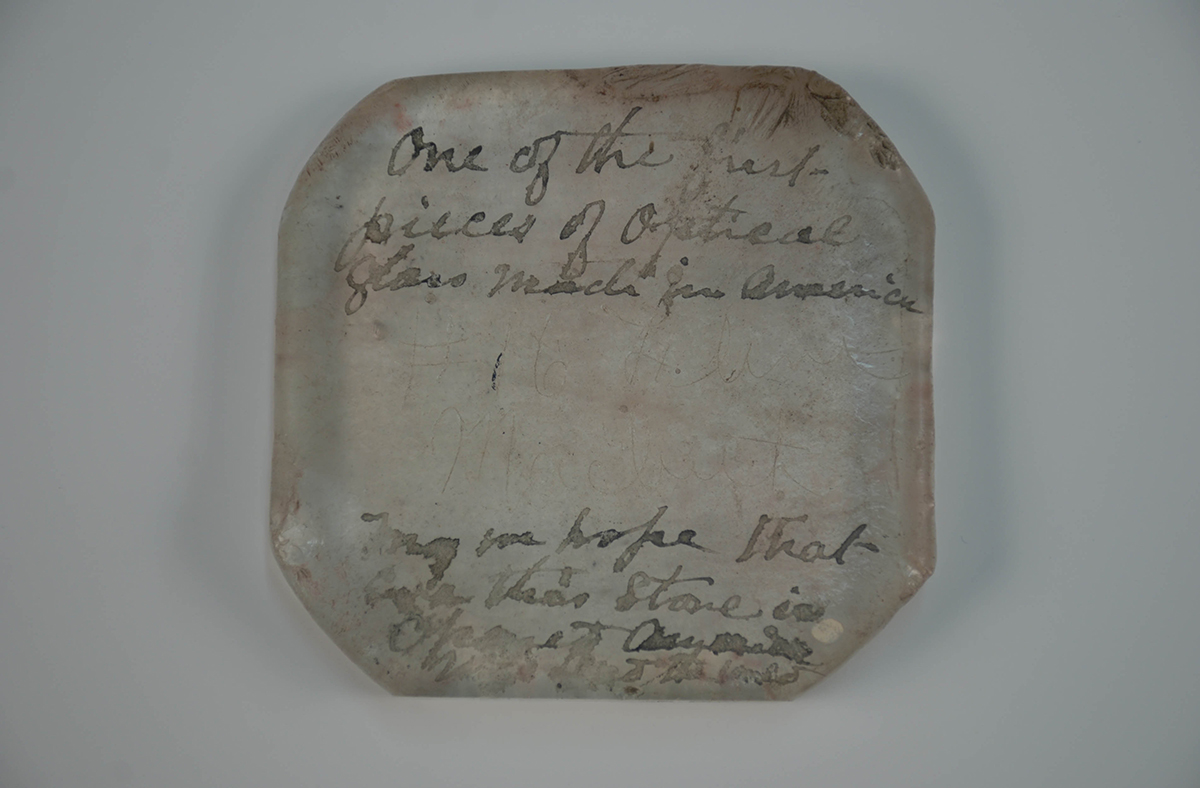

The contents were carefully assembled by Brashear after the building was completed. Brashear was largely self-taught in his profession and his desire for perfection led him to be recognized as one of the best optical instrument makers in the country. The contents of the time capsule he assembled are much more than a simple record of the man, his business, or the times. They provide us with an intimate look at Brashear’s career and personal life, documenting the people who helped him achieve his dream of building scientific instruments to explore the stars.

John Brashear came of age as a scientist and inventor as the discipline of science emerged in America. Many noted inventors of his time, from George Westinghouse to Thomas Edison, had no formal schooling. They were tinkerers or mechanics whose observation and exploration of the physical world, matched with a creative and questioning mind, led them to new ideas. While working as a millwright on the South Side, Brashear and his wife, Phoebe, began building their own lens and telescope during their free time.

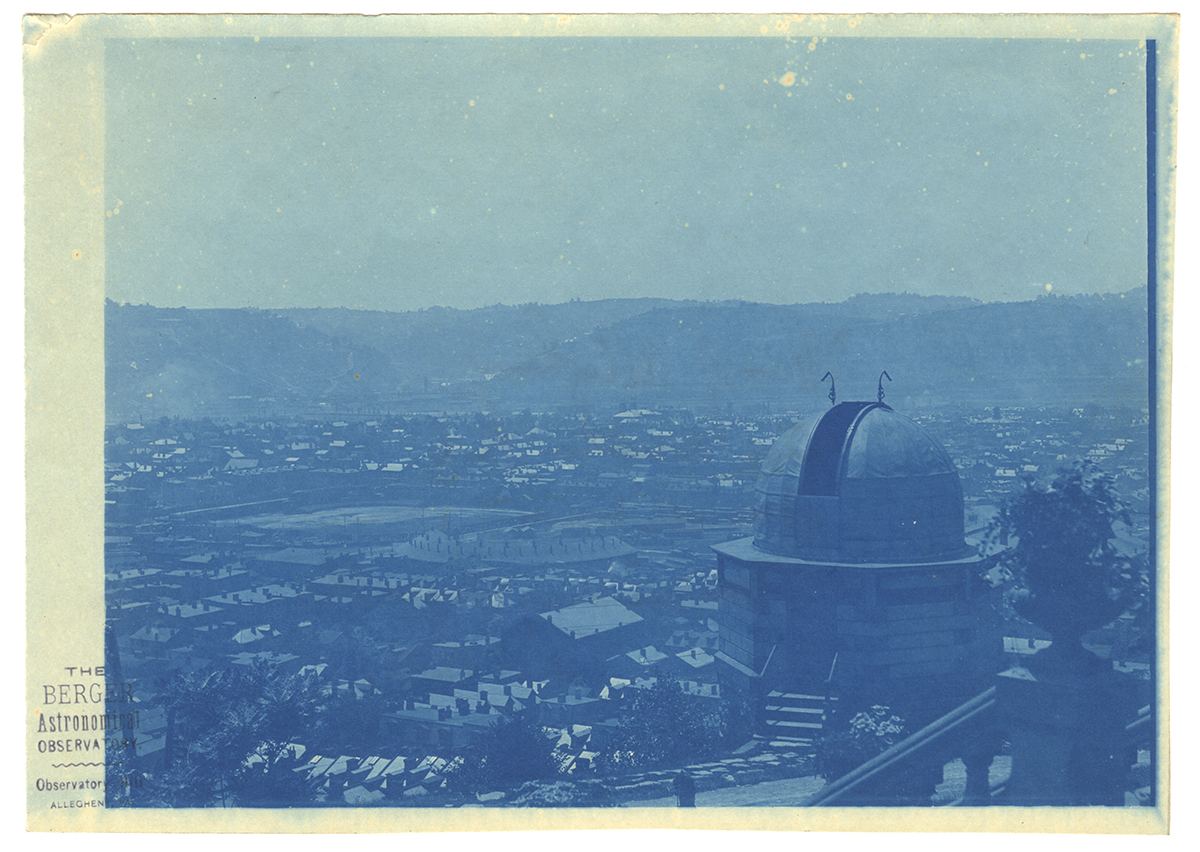

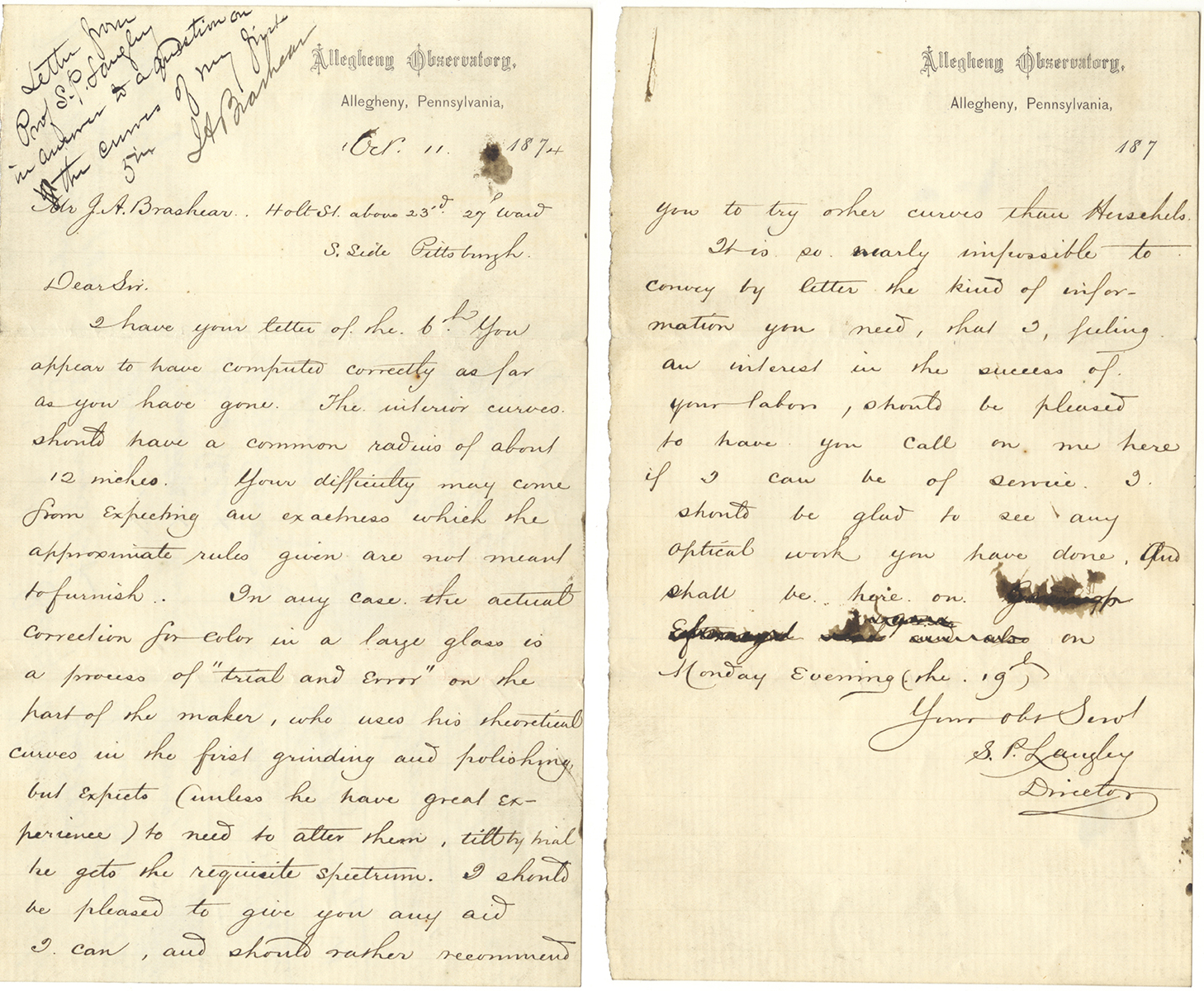

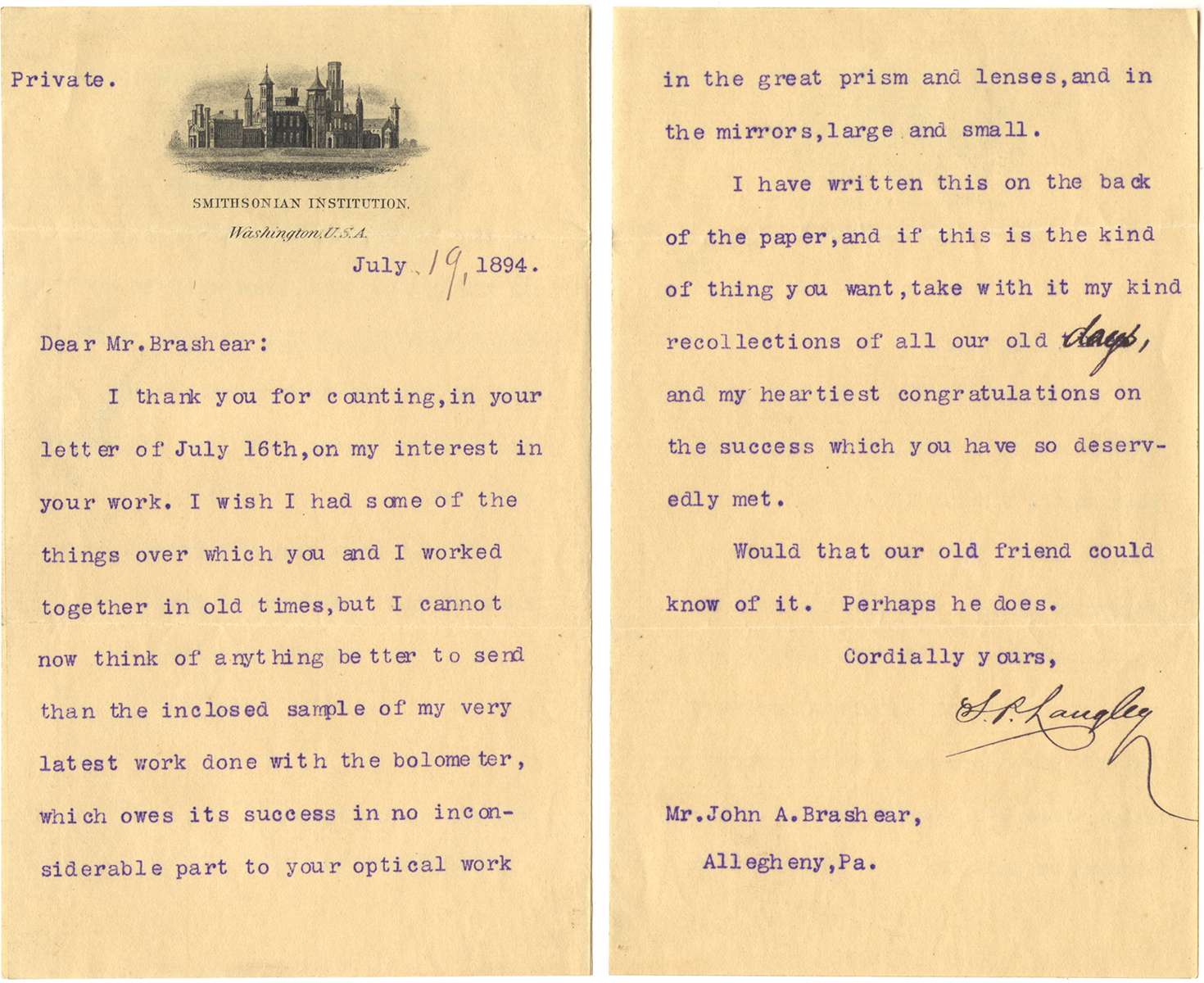

In a letter dated Oct. 11, 1874, which is found in the time capsule, Brashear mustered the courage to write to Samuel Pierpont Langley, the first director of the Allegheny Observatory and a professor of astronomy at the Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh), to ask him to evaluate the quality of the lens and his advice on improving it. As an amateur, it must have been incredibly intimidating for Brashear to approach an established man of science like Langley. Brashear described when they met in person: “with fear and trembling, I unwrapped from a red bandana handkerchief my first five-inch objective which my wife and I had made. His encouragement then and afterwards made my subsequent work easier by far.”[1]

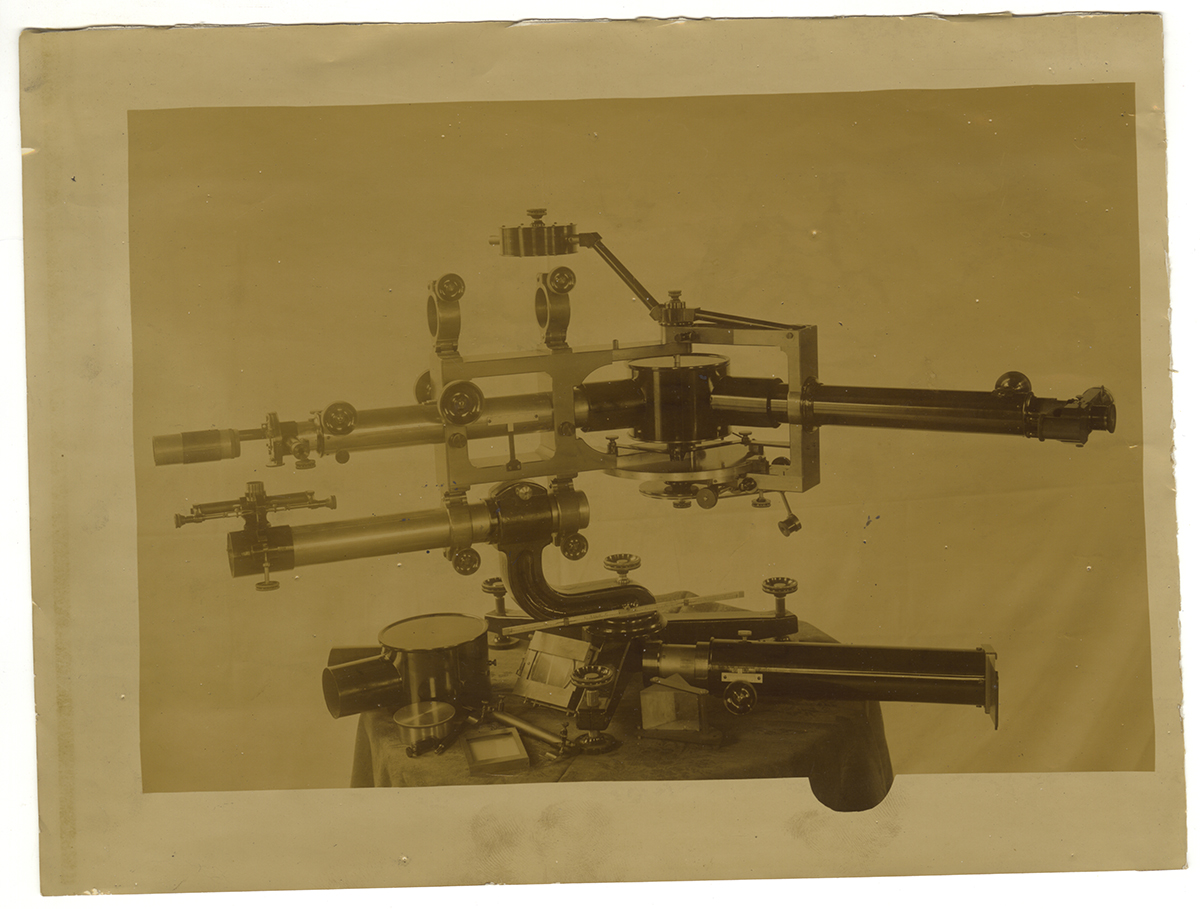

More than just an amateur attempt, the high quality of Brashear’s first lens greatly impressed Langley. As a result of that meeting, Brashear was introduced to the larger scientific world and several wealthy patrons of the sciences that allowed him to begin working on astronomical instruments full time. With his love of the stars and mechanical problem solving skills, Brashear built some of the finest optical instruments ever made, many of which are still in use today. He began working on astronomical devices full time in 1881, and by the 1890s, astronomers and scientists throughout the world were using his lenses, mirrors, telescopes, and scientific tools to make countless discoveries.

The letters, photographs, and ephemera in the time capsule give rare insight into the people that John Brashear held dearest in his life and work while also demonstrating the breadth of his impact on Pittsburgh and the scientific world. To Brashear, the memories of “his friends in this profession are to-day treasures of greater worth than gold or precious stones.”[2] We are fortunate that Brashear decided to place so many pieces of his life into this box so that one day others might learn from and be inspired by his accomplishments.

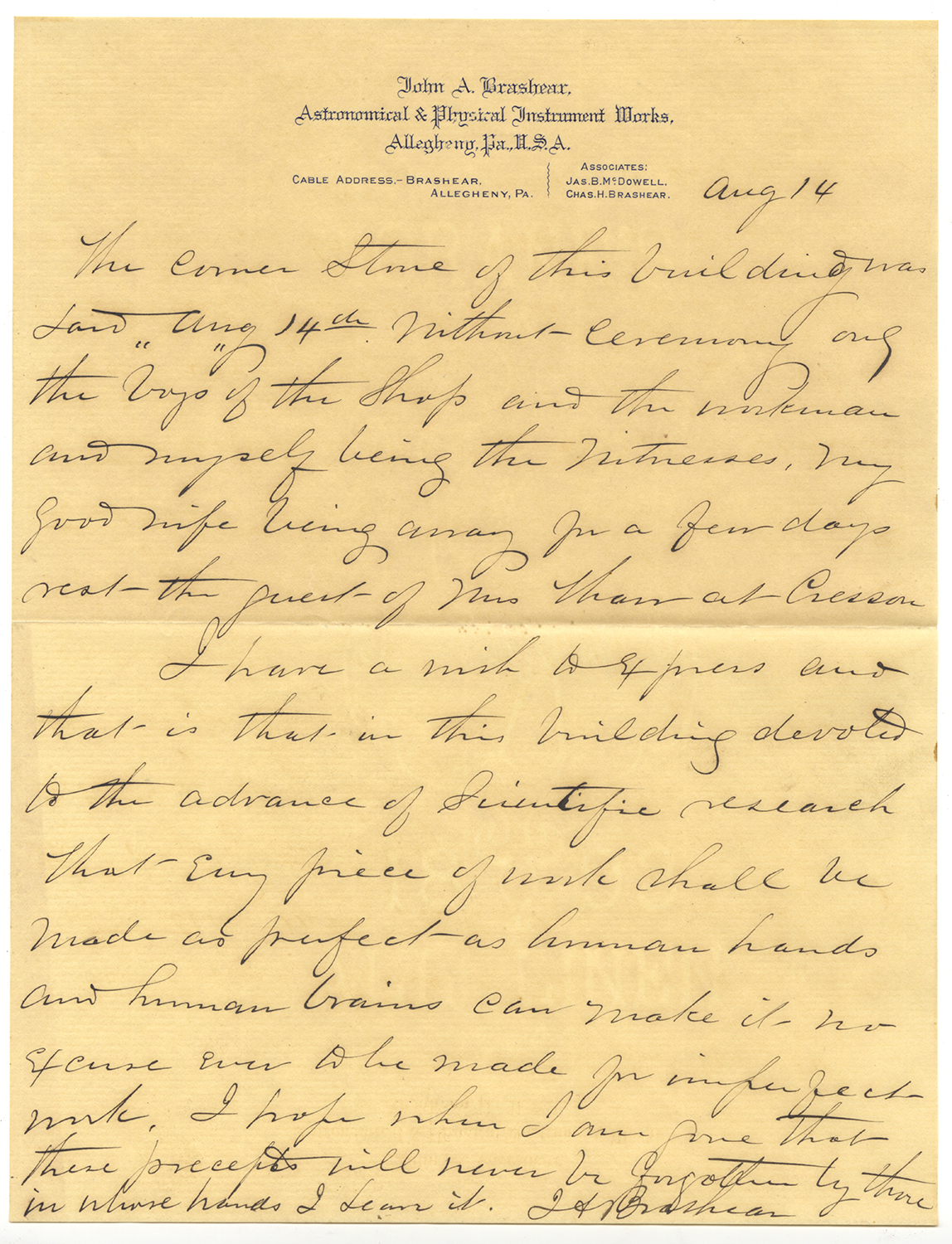

As Brashear writes in a letter that was found at the top of the time capsule, “I hope when I’m gone that these pieces will never be forgotten by those in whose hands I leave it.” With this time capsule, his legacy and desire to share his knowledge of the beautiful world in which we live is now firmly preserved at the History Center.

Visit the Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation exhibition on the History Center’s second floor to see the time capsule box and some of its contents.

You can also read the full article about John Brashear and the contents of the time capsule in the Summer 2016 issue of Western Pennsylvania History.

—

[1] John A. Brashear and William Lucien Scaife, ed., John A. Brashear: The Autobiography of a Man Who Loved the Stars (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2001), 131.

[2] Ibid., 38.

Liz Simpson is the assistant editor of Western Pennsylvania History Magazine and assistant registrar at the at the History Center.