The Day Pittsburgh Stood Still: September 9, 1947

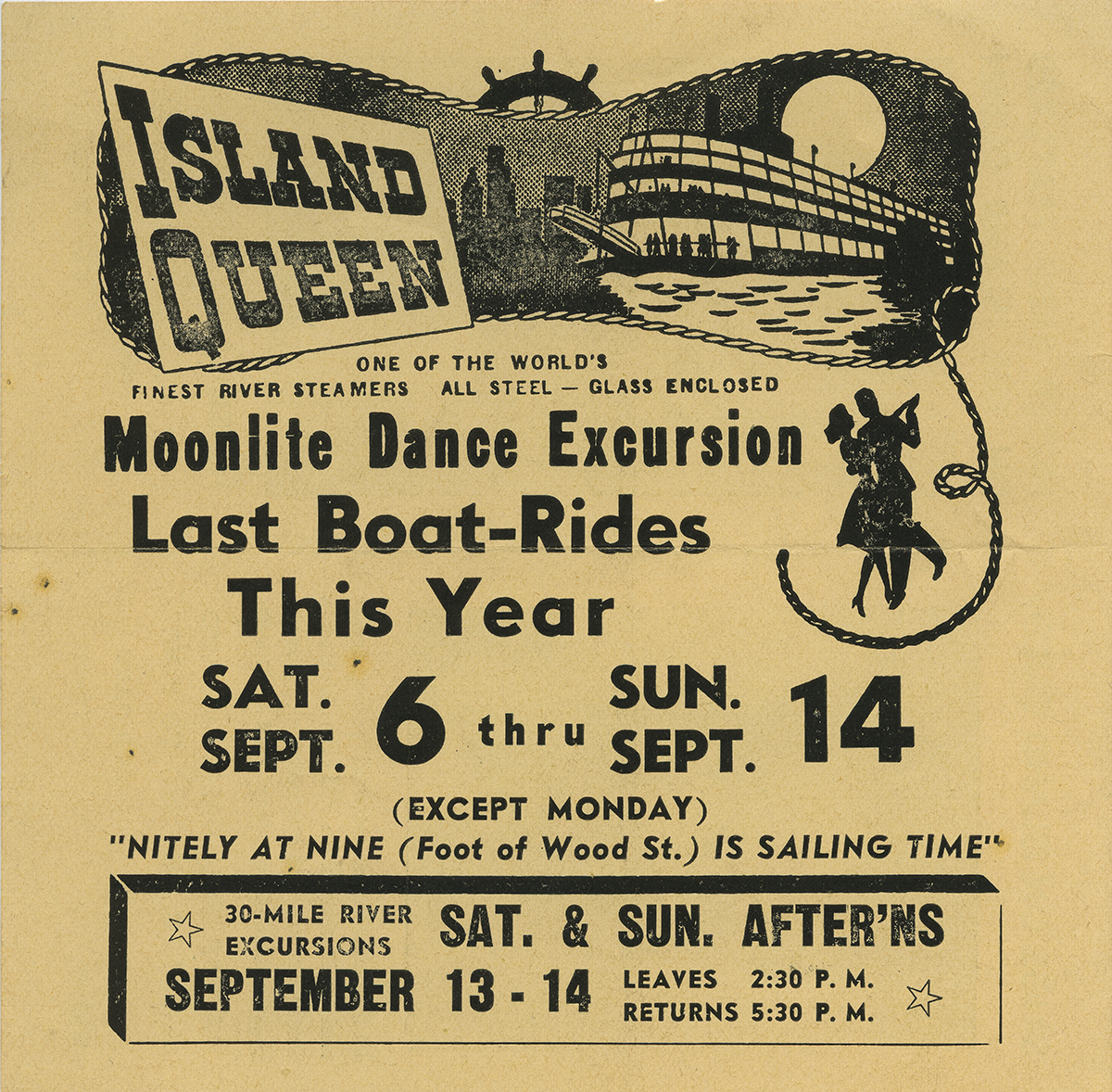

It was a such a simple repair. As Captain Charles Hall walked off the Cincinnati-based excursion steamer Island Queen, docked along the Monongahela wharf in Pittsburgh, he brushed against a loose stanchion. He called to the chief engineer: couldn’t that be fixed? The Island Queen faced a busy schedule. Arriving on September 6, she had already run trips on Saturday, Sunday, and Monday. Now, on her day off, the post could be secured before passengers began boarding again the following day.

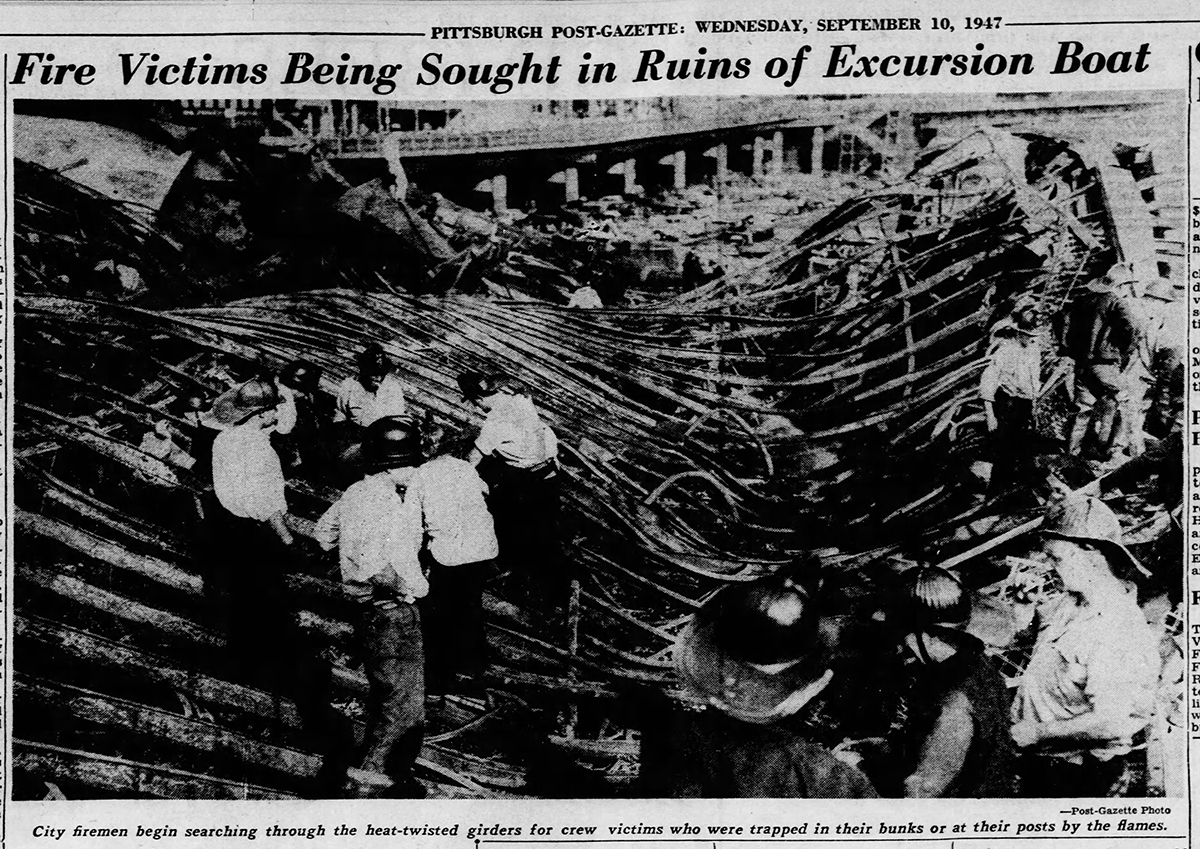

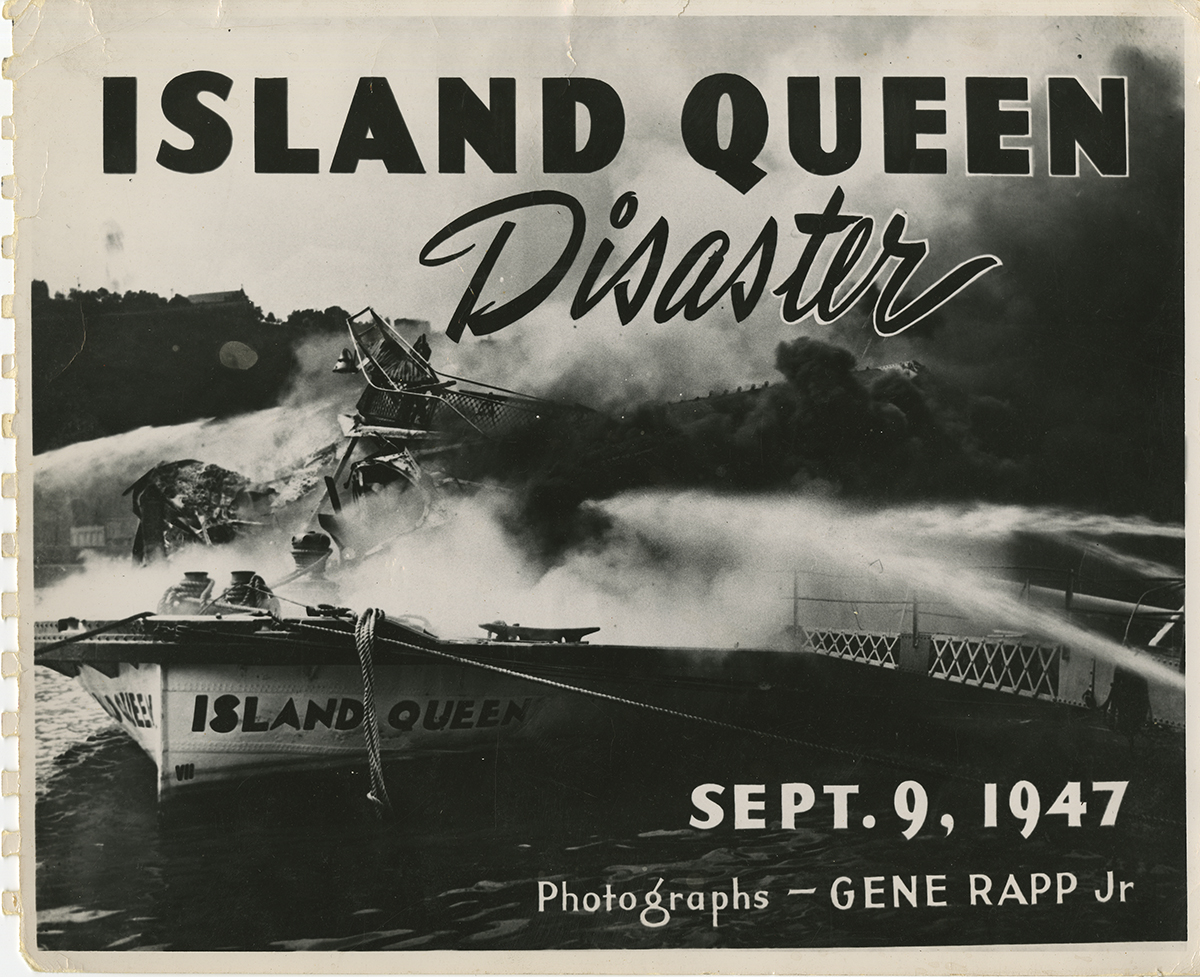

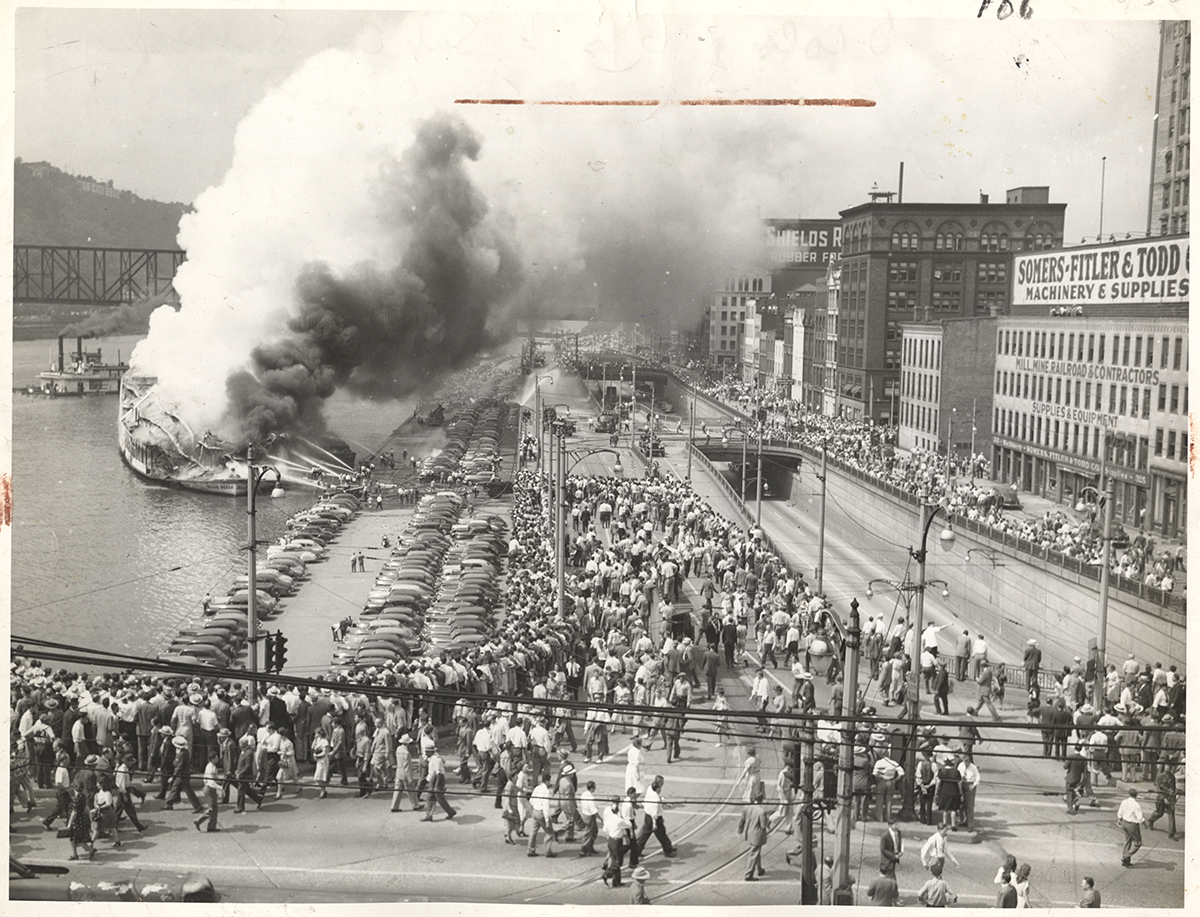

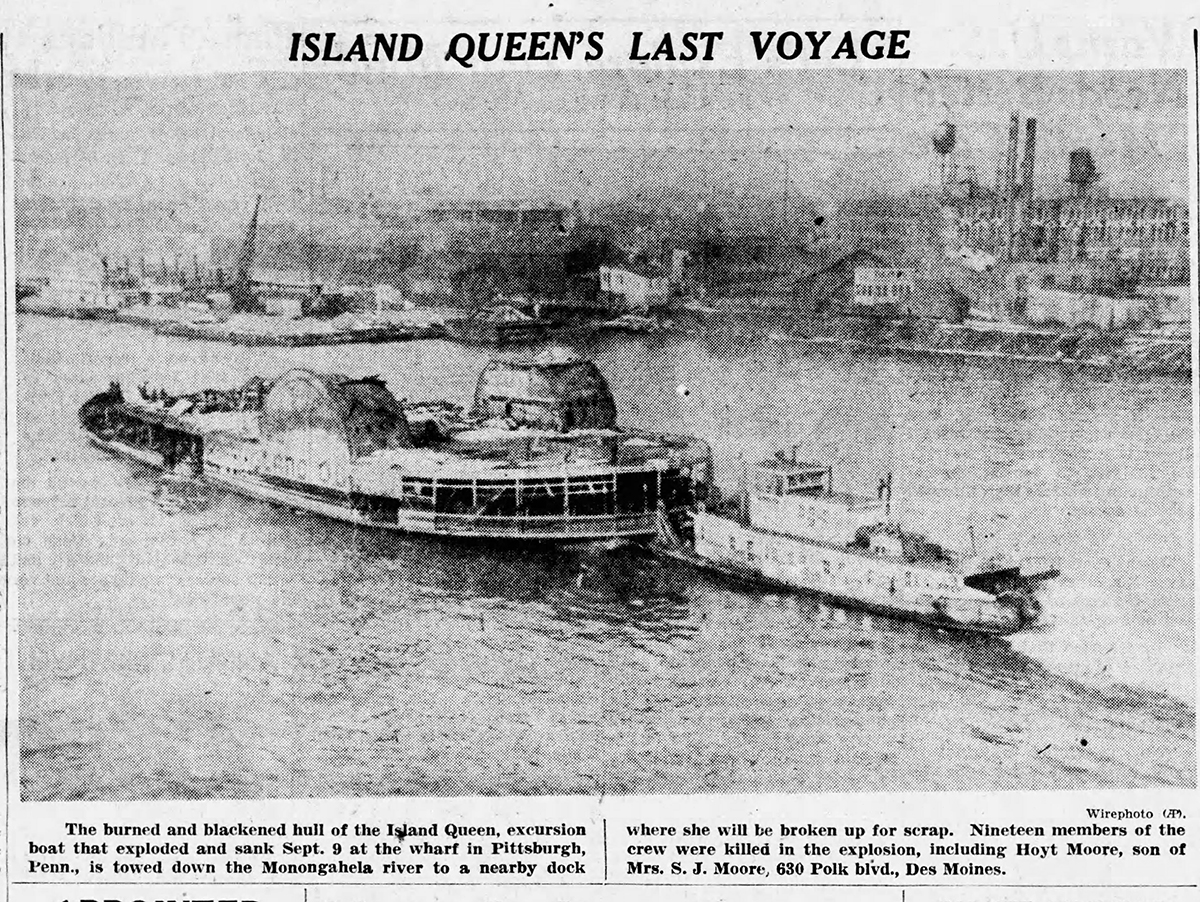

The chief engineer made a fateful decision. He opted to fix the post by welding it rather than using a rivet. As he made the repair, hot metal and an electrical arc from the welding torch burned through the boat’s deck and into a fuel tank below. The tank exploded, igniting a fire that engulfed the boat’s five decks in under ten minutes. Nineteen crew members died, unable to escape the inferno.

The blast, described like “an atomic bomb,” was heard miles beyond downtown Pittsburgh. Cars parked on the wharf were set ablaze and buildings were damaged by the explosion and flying debris. People rushed to the riverfront. So many crowded onto the Smithfield Street Bridge that officials feared a collapse. Spectators on Mount Washington lined Grandview Ave. Even schools such as Saint Mary of The Mount High School couldn’t fight the excitement: students and teachers rushed out of class to get a better view of the calamity below. (Full disclosure: my mother was one of those students. Her memories of the explosion remain vivid, even so many years later.)

The fiery end of the Island Queen became part of Pittsburgh lore, one of the most dramatic moments in the city’s history. But lost in the pathos of that day was the Island Queen’s larger story, a history that linked the boat to the earliest days of western river steamboats and Pittsburgh’s own riverine heritage.

The lost steamer Louisville

The Island Queen wasn’t supposed to be the Island Queen. The boat was commissioned in the early 1920s as one of a pair of deluxe river steamers operating out of Cincinnati, Ohio. The effort was funded in part by Pittsburgh Industrialist John W. Hubbard. Hubbard had interests in multiple river transport lines and was president of the venerable Cincinnati & Louisville Packet Line, a fleet of packet steamers dating back to 1819, at the dawn of western river steamboat travel.

The two new boats were to be named Cincinnati and Louisville. While they would look like traditional riverboats, their construction was rooted in the new century. They would be made of steel. The task of building their steel hulls went to the Midland Barge Company, an Ohio River firm in Midland, Pa., Beaver County. Midland Barge, a steel construction company, won the contract with an aggressive low bid, one that perhaps hinted at their inexperience with this kind of work. The twin sidewheelers were to be huge, each nearly 300 feet long. “Among the largest to be placed in commission” noted local newspapers.

The scale challenged Midland’s capacity. Author John White, a former Curator of Transportation at the Smithsonian who co-wrote the book “The Island Queen: Cincinnati’s Excursion Steamer” (1998), reports that the company may have turned to experts upriver at the American Bridge Company to troubleshoot solutions. At last, the Cincinnati’s hull was completed in July 1923 and sent downriver, where the rest of the boat would be finished. Work in Midland started on its twin.

As the project dragged on and expenses mounted, concern grew over the scheme’s viability and backers pulled out. The Louisville was never finished. Although Midland Barge reported that the boat’s steel hull was “about 80 per cent completed” by October 1923, the unfinished craft was left in limbo.

The new Island Queen

Eventually another buyer stepped in. The former Louisville became an excursion steamer, ferrying passengers to Cincinnati’s Coney Island amusement park. With a new design by Pittsburgh marine architect Thomas Rees Tarn, the craft’s superstructure expanded into five decks. What she gained in space she lost in luxury – these decks were large, glass-enclosed open spaces designed to accommodate around 4,000 people. The boat also featured a two-story ballroom at nearly 250 feet long.

By 1925, the finished boat was christened the Island Queen. Technically, it was the second Island Queen. True to the precarious lives of river steamers, the first Island Queen, built in 1896, burned in a Cincinnati wharf fire in 1922. It was an omen of things to come.

The Island Queen was never a regular visitor to Pittsburgh. She spent her summers ferrying passengers to and from Coney Island, then after Labor Day headed out in search of off-season revenue. Usually, the boat churned south, where warmer weather offered greater prospects for business. Her first visit north was in 1931, when newspaper ads heralded “the largest steamer ever in Pittsburgh.”

A decade passed before the Steel City saw the Island Queen again. In 1941, the boat underwent repairs at Dravo’s marine yard on Neville Island twice. In January, the hull received a general inspection and repair. Then, in November, the Island Queen received a more extensive overhaul to widen and stabilize the hull. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette anticipated that the large steamer would “attract considerable attention.” This is probably true, although as the work stretched through December 1941 and into January 1942, no doubt attention turned away from the novelty of a large pleasure craft to the anticipation of the submarine chasers and LSTs that Dravo would start building to fight World War II.

It would soon be the end of an era. When the Island Queen next arrived on that fateful trip in 1947, she was supposed to offer public excursions through September 14 with one final private charter the following Monday. The boat never made that final booking.

When the Island Queen exploded, she prompted a final round of headlines in Pittsburgh. But more than that, she took a piece of Western Pennsylvania’s boat building heritage with her.

For Further Reading

Tragic explosion on excursion steamer Island Queen, The Digs, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 28, 2013.

John White and Robert White, The Island Queen: Cincinnati’s Excursion Steamer. Akron, Ohio: University of Akron Press, 1998. (This book can be found in the Detre Library & Archives, call number: VM461.5.I83 W49 1998 long)

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.