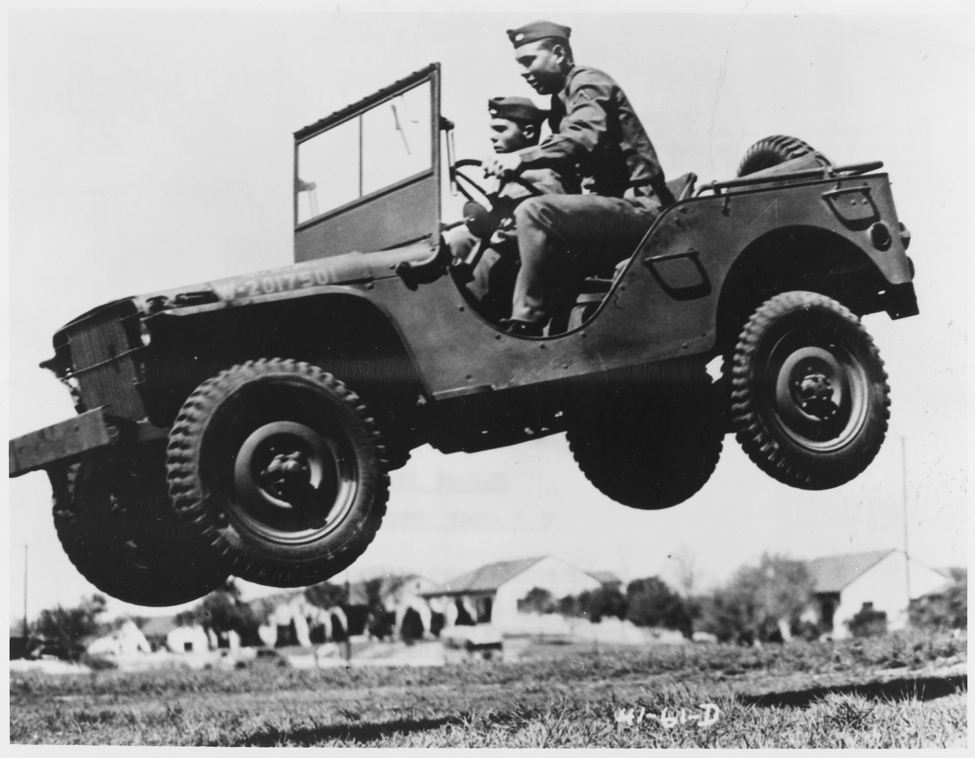

Created of necessity on the eve of World War II, the versatile combat vehicle that became known the world over as the “Jeep” demonstrated the best American ingenuity had to offer. The jeep’s evolution as a civilian vehicle reflected rapidly advancing American technology and the changing society of the post-war boom years.

In 1940, the War Department (think about how sensibilities have changed—in 1940 what is now known as the Department of Defense was still called the “War Department”) sent a Request for Proposals (RFP) to 135 American carmakers (think about that for a moment: in 1940 there were more than 135 car makers in America!). The army wanted a motorized vehicle to replace the horse (most of the world’s armies were then still largely horse-drawn). The new vehicle had to be able to do anything a horse could do, except eat hay. It had to climb a 30-degree grade, pull field artillery, and traverse any kind of terrain in all weather conditions. Government specs required that the new vehicle could not weigh any more than a large horse—2,000 pounds was the limit.

To make more difficult the job of designing and building this mechanical marvel, the War Department determined that companies responding to the RFP had to deliver their prototypes to Camp Holabird, Maryland, in just 49 days. Few engineers employed by the nation’s largest carmakers—Ford, General Motors, Willys Overland—believed such an engineering and manufacturing feat possible.

But the little American Bantam Car Company of Butler, Pa. was determined to meet the deadline and show the big guys what they could do. The team in Butler had recently questioned their own business strategy. No one in America, it seemed, wanted the sporty midget cars they were producing under a patent agreement with the British Austin Company. Gas was cheap in those days and Americans preferred big cars. The Bantam Company owners were considering filing for bankruptcy and padlocking the Butler factory doors. But then the RFP arrived.

The story goes that the engineers stayed up all night at a diner and sketched the design for the jeep. With Detroit engine designer Karl Probst, the team worked day and night to produce the little car within the 49-day limit. They cobbled it together from parts on hand and designed new features—including a workable four-wheel-drive system—as needed. Time was so short, they drove their Bantam Reconnaissance Car (BRC) to the Maryland test site. Of course, they could have trailered their prototype, but they needed to break in the just-assembled engine. That was how close they cut it to squeak in just short of the 49-day deadline.

It turns out, Bantam was the only company to deliver its test vehicle on time—and their BRC was exactly what the army was looking for! It appeared that Bantam had hit the army contract jackpot. Government inspectors soon discovered, however, that Bantam did not have the capacity to manufacture jeeps on a large scale. Financial success eluded the little car maker with the “can do” attitude, for when Japanese Imperial forces attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States found itself in a shooting war, the Defense contract was pulled from Bantam and awarded to Willys Overland of Toledo, Ohio. Willys turned out more than 350,000 jeeps and additional contracts went to Ford which cranked out another 300,000 vehicles by war’s end.

Bantam did contribute to the war effort by building the small two-wheeled ammo cart trailers that were towed behind jeeps. But the little Western Pennsylvania company that pioneered the army’s all-terrain, workhorse jeep went out of business not long after the war.

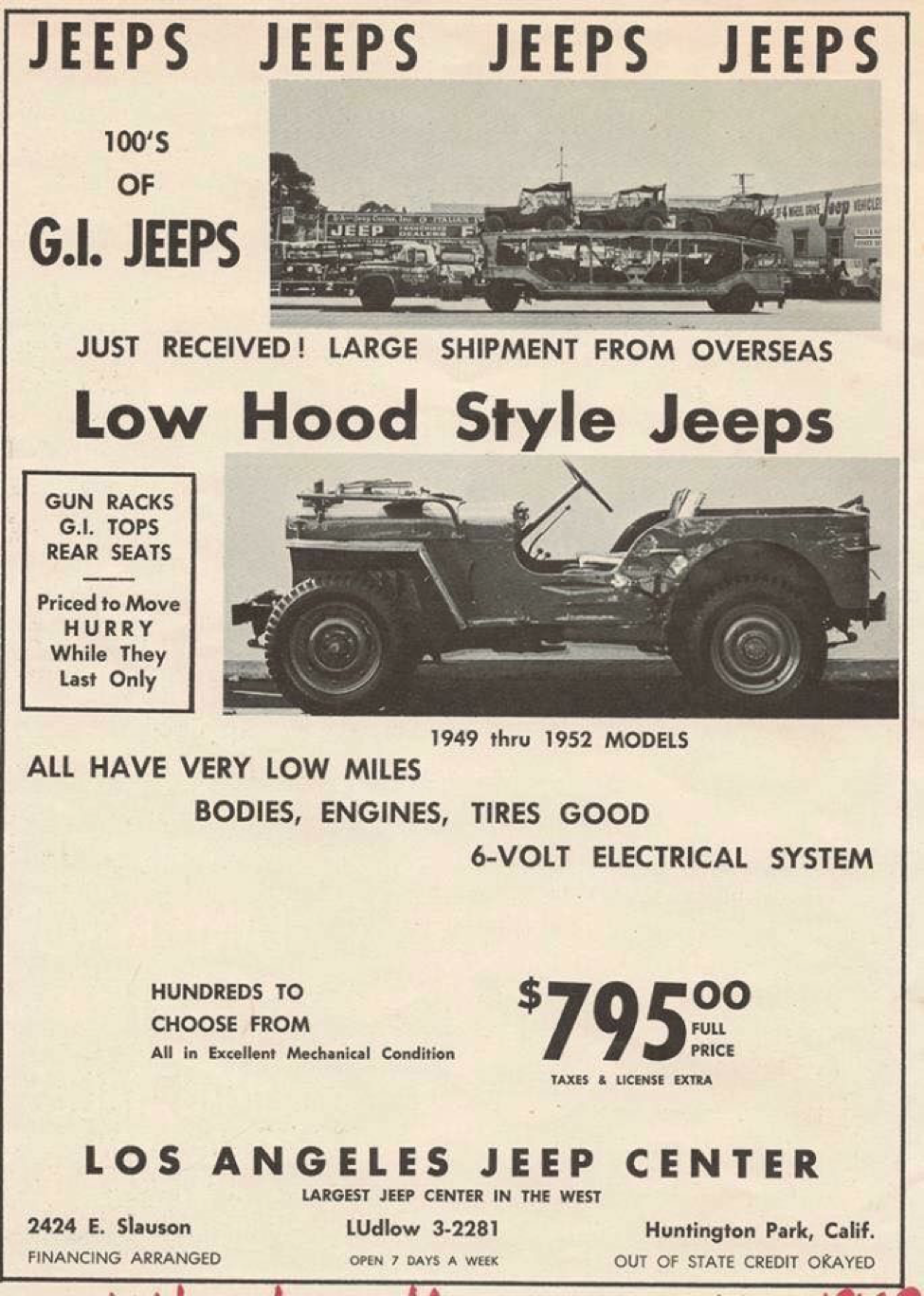

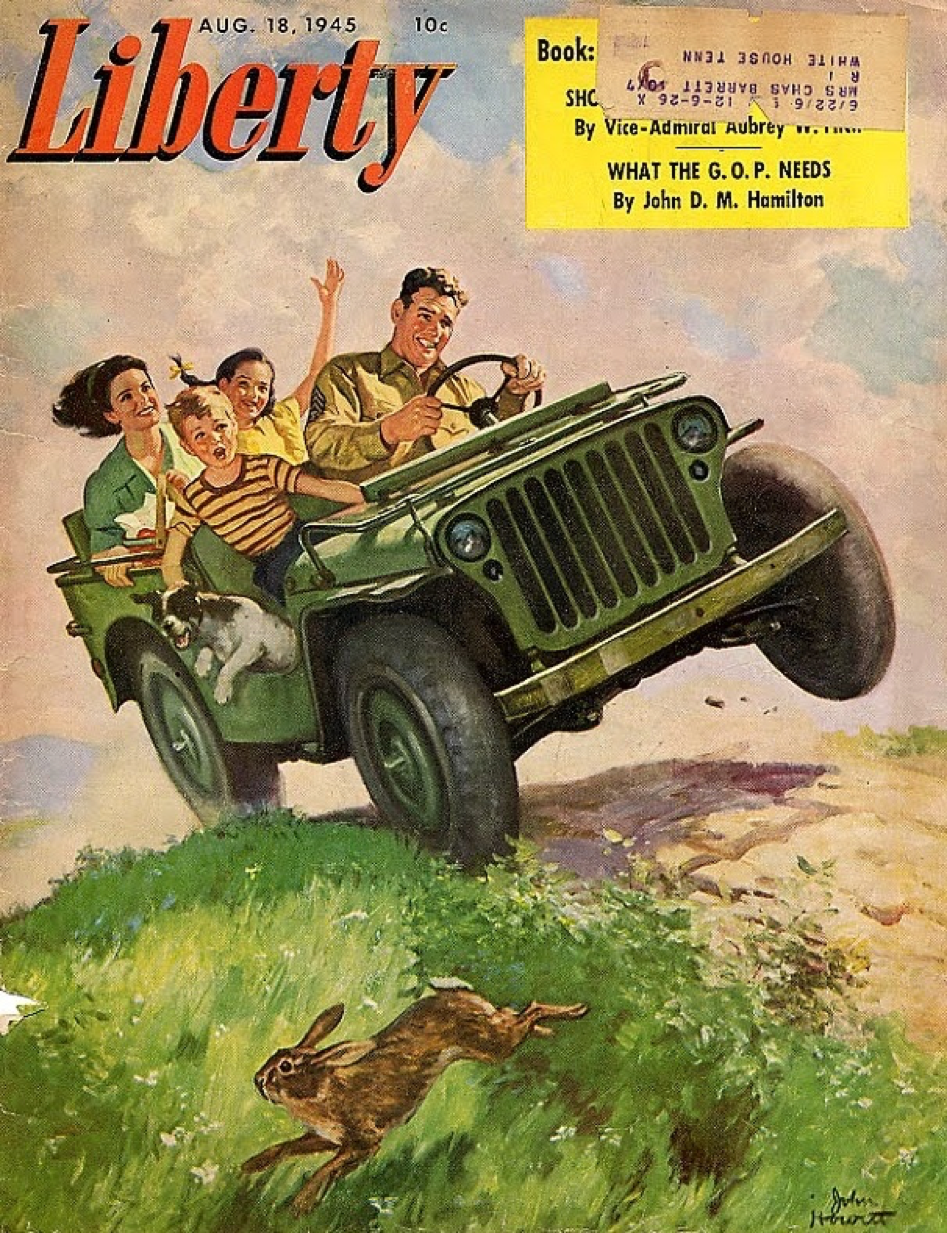

But the jeep lived on. In fact the popularity of the little army vehicle boomed after the war. Civilians repurposed surplus jeeps for everything from cheap transportation to farm work and even postal delivery cars. Many of the young GI’s (many in their teens and early twenties) who had gone to war had never driven a car before. The jeep was their first car. When the men came home they wanted two things—a wife and a car (probably in that order).

You can imagine the conversation between the newlyweds: “Hey, honey, let’s get a jeep!” With a look of stern pragmatism, she might reply, “Are you nuts? Where will we put the groceries? Where are the kids going to go? That thing doesn’t even have a roof!”

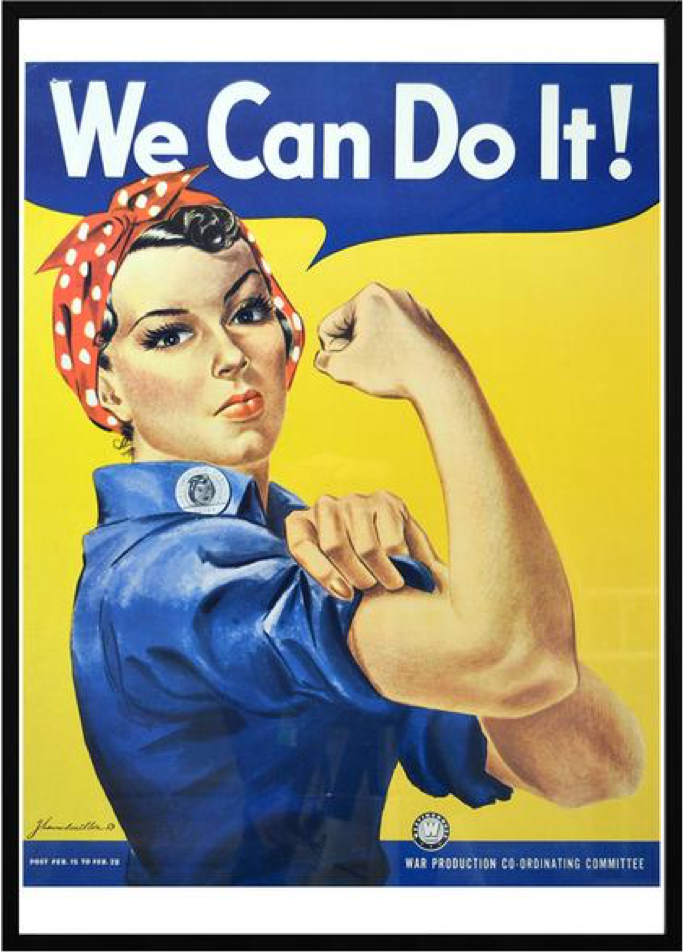

Before the war, it is estimated that only ten percent of American women had driver’s licenses. But on the home front during the war years, Rosie the Riveter had to get to work and “stay-at-home moms” could not just stay at home. They had to do everything—including driving—without the help of their men who were away at war.

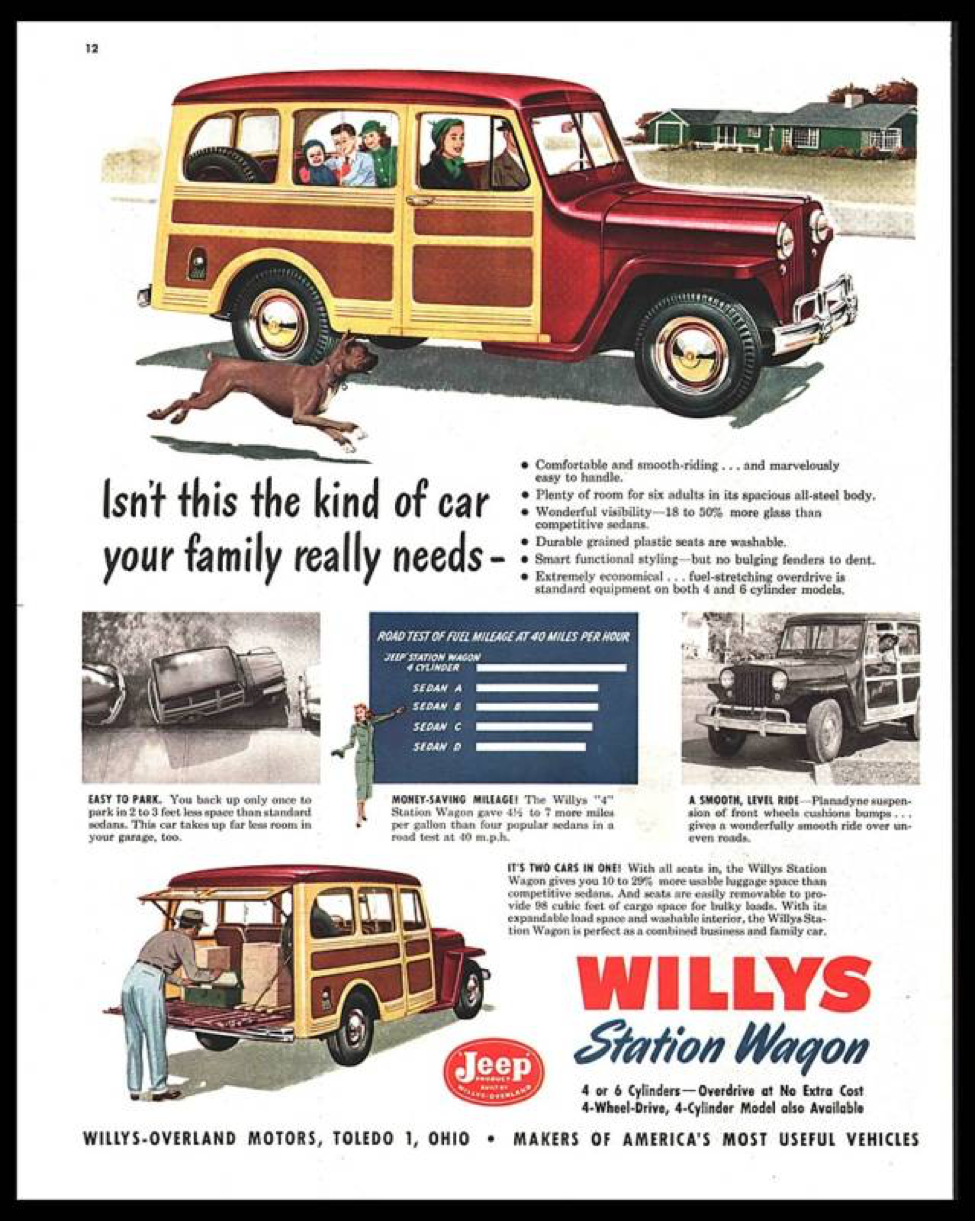

After the war, Willys quickly retooled to make Civilian Jeeps (dubbed “CJs”) in a variety of colors and useful configurations, but the real eye popper was a Jeep Station Wagon designed with women in mind. Magazine ads announced: “see the Jeep as a lady.”

The three-tone paint scheme on the “ALL-STEEL” body mimicked the woody station wagons then in vogue. By 1949, the Jeep Station Wagon was available in four-wheel drive—just like a real army jeep—and the Sport Utility Vehicle (SUV) was born.

Born of necessity and baptized in battle, the jeep became a symbol of American ingenuity and “can-do” spirit. Both Eisenhower and Patton numbered it among the most influential pieces of equipment in the winning of WWII and GIs loved the miraculous all-purpose vehicles. During the post war boom years, men wanted jeeps and women with driver’s licenses and new-found independence and purchasing power embraced the Jeep Station Wagon as a practical family car. The rest is … history.

Andy Masich is the president and CEO at the Senator John Heinz History Center.