Tips for conserving correspondence

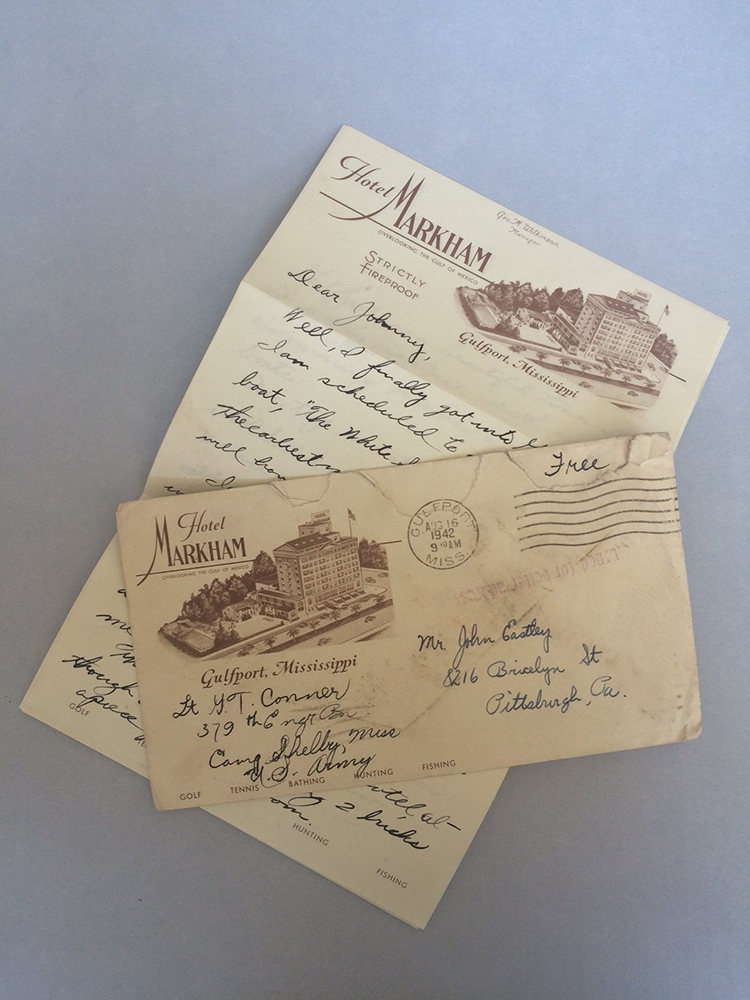

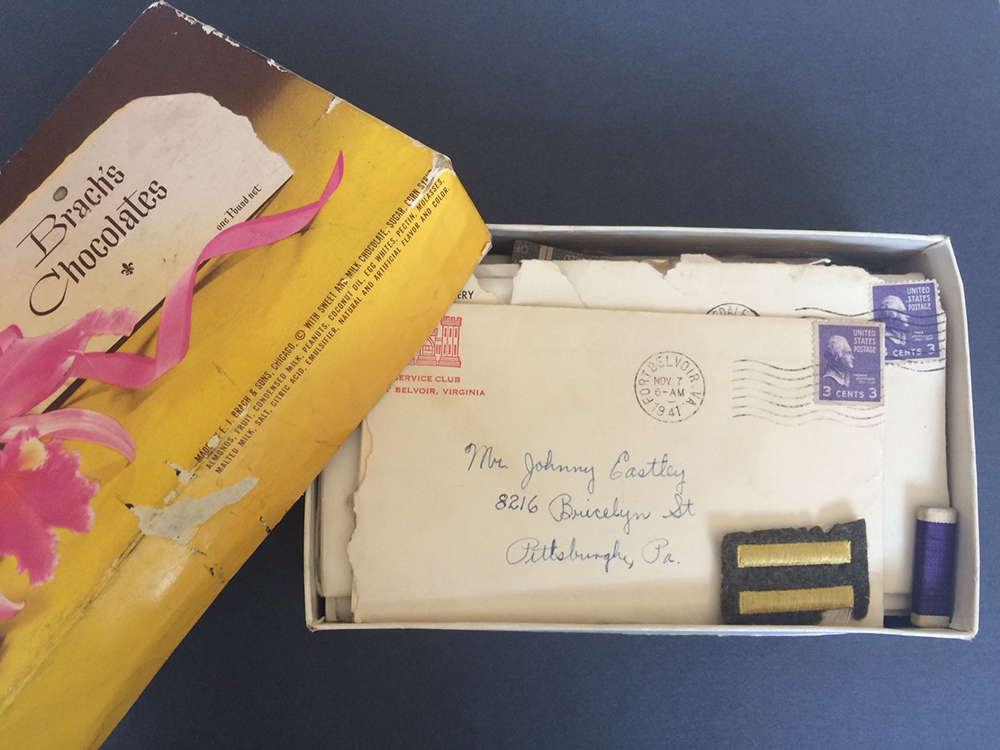

A candy box may seem like an unusual container for a story, but within an old Brach’s chocolate box, a variety of wartime correspondence and paper articles relating to a local veteran’s World War II experiences were found.

It’s not unusual to see similar items brought to the History Center’s Museum Conservation Center for assessment. Correspondence has been found inside antique writing desks, baskets, and even toolboxes. Each “archive,” if you will – an archive is defined as the place where records are kept – is its own treasury of information.

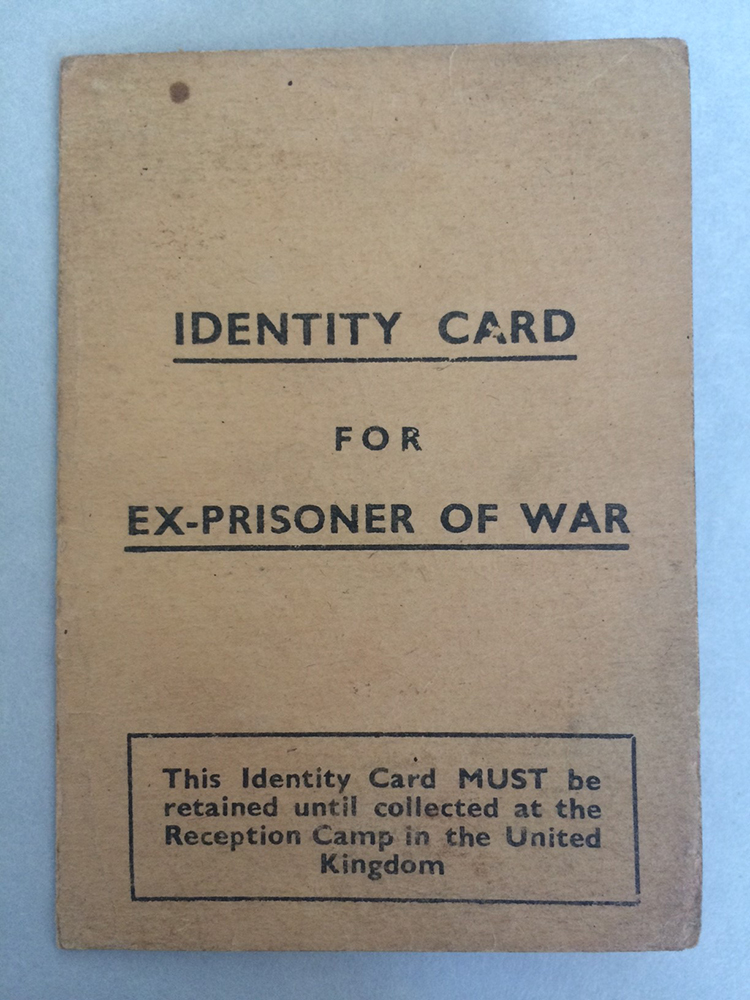

The correspondence inside this candy box varies in format. There are handwritten letters, typewritten notifications, ID cards, a map, and news clippings. They are similar to a time capsule, dating from 1941 until 1953.

One way to begin processing information from your own family is to sort things out categorically (letters, official documents, photos, ephemera, etc.) first and then chronologically (e.g. 1941-1953) second. Letters written by servicemen during the war to friends and relatives are often arranged alphabetically by writer’s name.

What follows are a few suggestions for reviewing your own trove of letters:

1. Separate photographs from papers as you go along. Be aware of any condition changes to the paper backing. Mold on paper, if present, should never be placed among other unaffected papers; the spores may spread through an entire collection of papers to a ruinous ending.

2. Place similar items within the same acid-free folder. Describe each item on the file tab in pencil (e.g. Correspondence, Glenn Conner, 1941-1953). Remove letters from envelopes and unfold them if they are not too brittle to be handled. Save the envelope with the letter (there may be an important date or location on the postmark), but separate the envelope from the letter with a sheet of acid-free tissue paper. This will help to keep any adhesive residue from the envelope isolated from the document.

3. Keep newspaper clippings in their own separate folder or page protector. Make a good photocopy on acid-free paper to file while you are processing your material. The high level of acidity in the composition of newsprint paper is evidenced by dark yellow “burning.” Over time, these clippings crumble and disintegrate very easily. The acid burn can easily be transferred into your primary documents if left next to newsprint and may affect their longevity and appearance as well.

All photos and items courtesy of Barbara Conner Antel and the Conner family.

The Museum Conservation Center offers a variety of workshops throughout the year dedicated to helping you learn more about taking care of your collections. Visit the events page to learn more. We welcome your inquiries about conservation concerns and can be reached at 412-454-6450 or [email protected].

Barbara Conner is the conservation services manager at the Senator John Heinz History Center’s Museum Conservation Center.