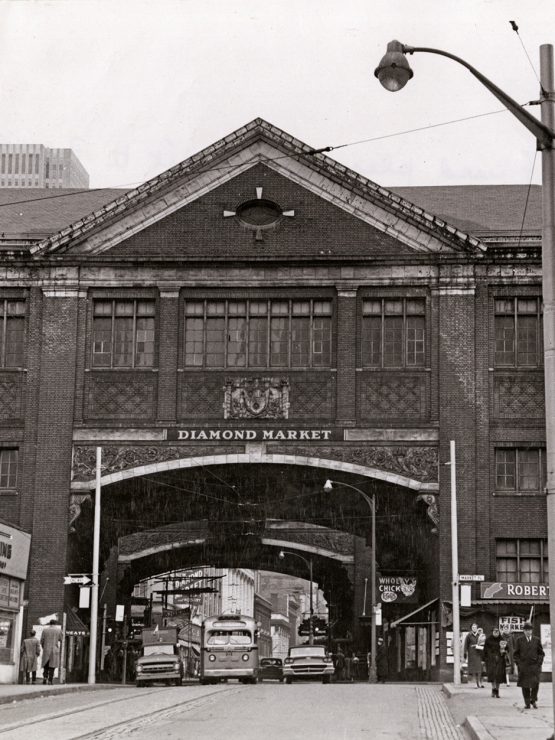

From 1915 until it was demolished in 1961, Diamond Market shaped the life of one of Pittsburgh’s oldest public spaces. The market hosted poultry shows and boxing matches, a roller-skating rink, and for a while, the Traffic Division of the Pittsburgh Police Department. It served as the starting point of a marathon, and in 1953, it was the focus of a Civil Rights action.[1] All the while, the building that sprawled over Diamond Street (now a re-routed Forbes Avenue) bustled with vendors selling meat, fish, baked goods, coffee, and produce. Some stands operated there for generations.

A Fate Years in the Making

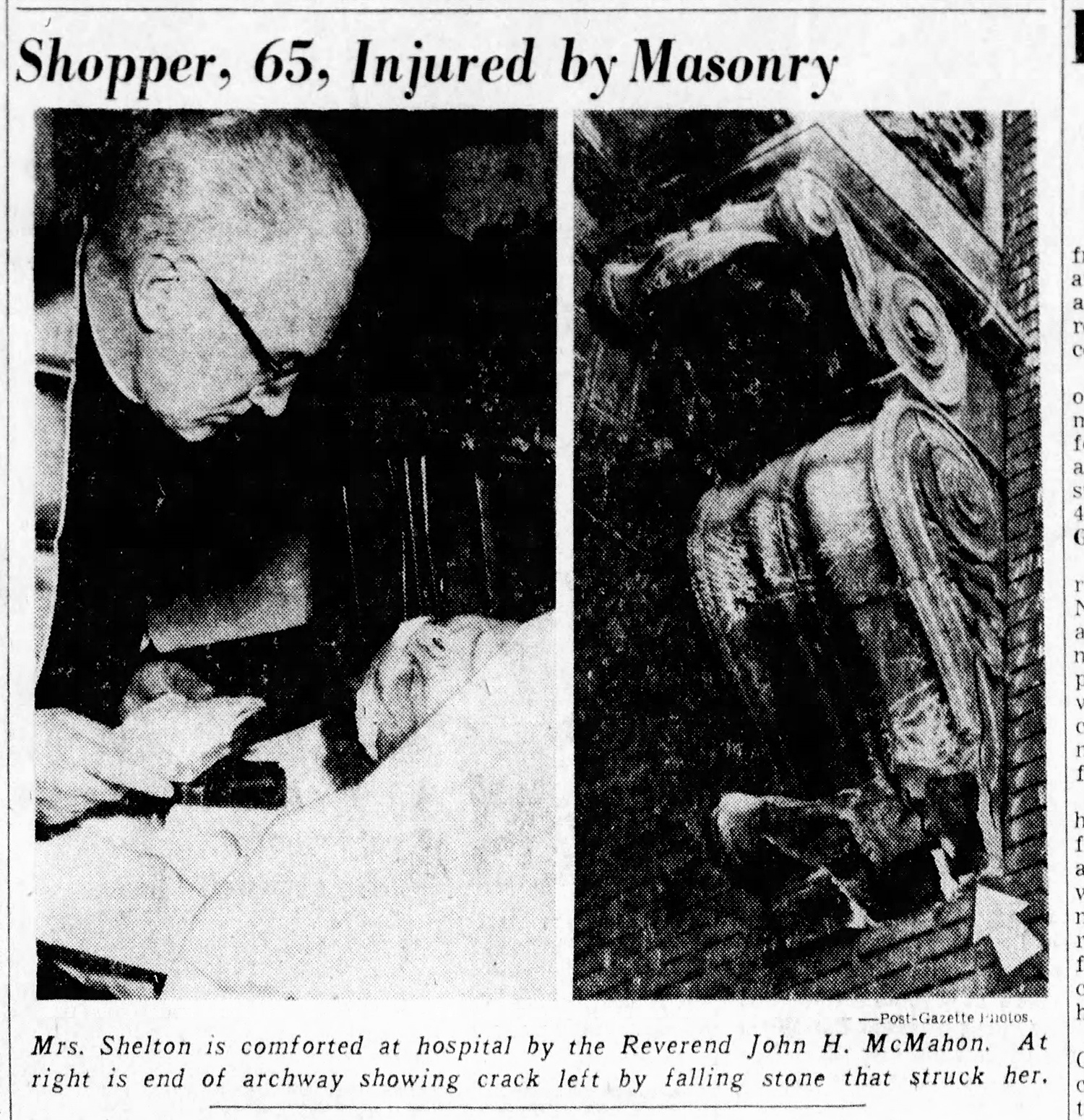

Built and run by the city but home to more than 40 small independent businesses, Diamond Market symbolized “old Pittsburgh.” Celebrated when it opened, the market became caught in time, straddling a changing consumer landscape and a modernizing city. When a 35-pound piece of a decorative cornice fell off the building in December 1959, seriously injuring a woman, it proved to be the final straw for a structure the city had been trying to remove for years.[2] But not before Diamond Market prompted one final debate in the spring of 1960.

“A Great Improvement”

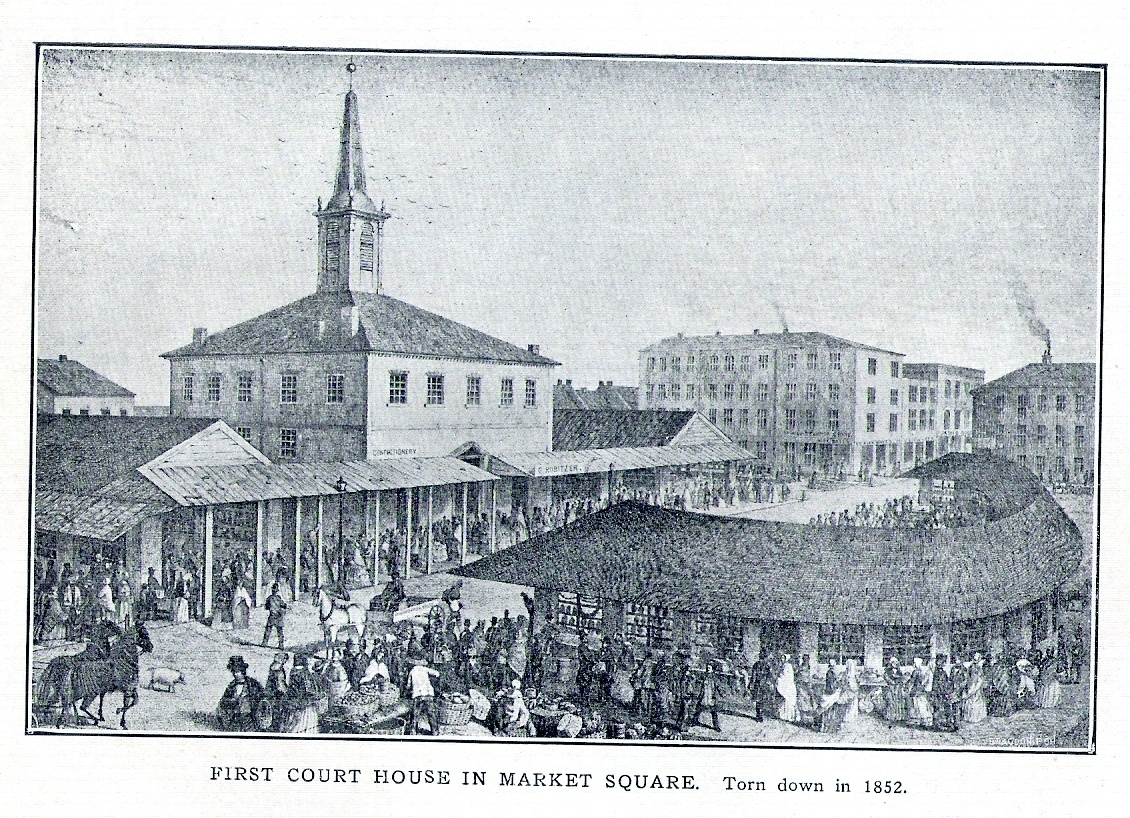

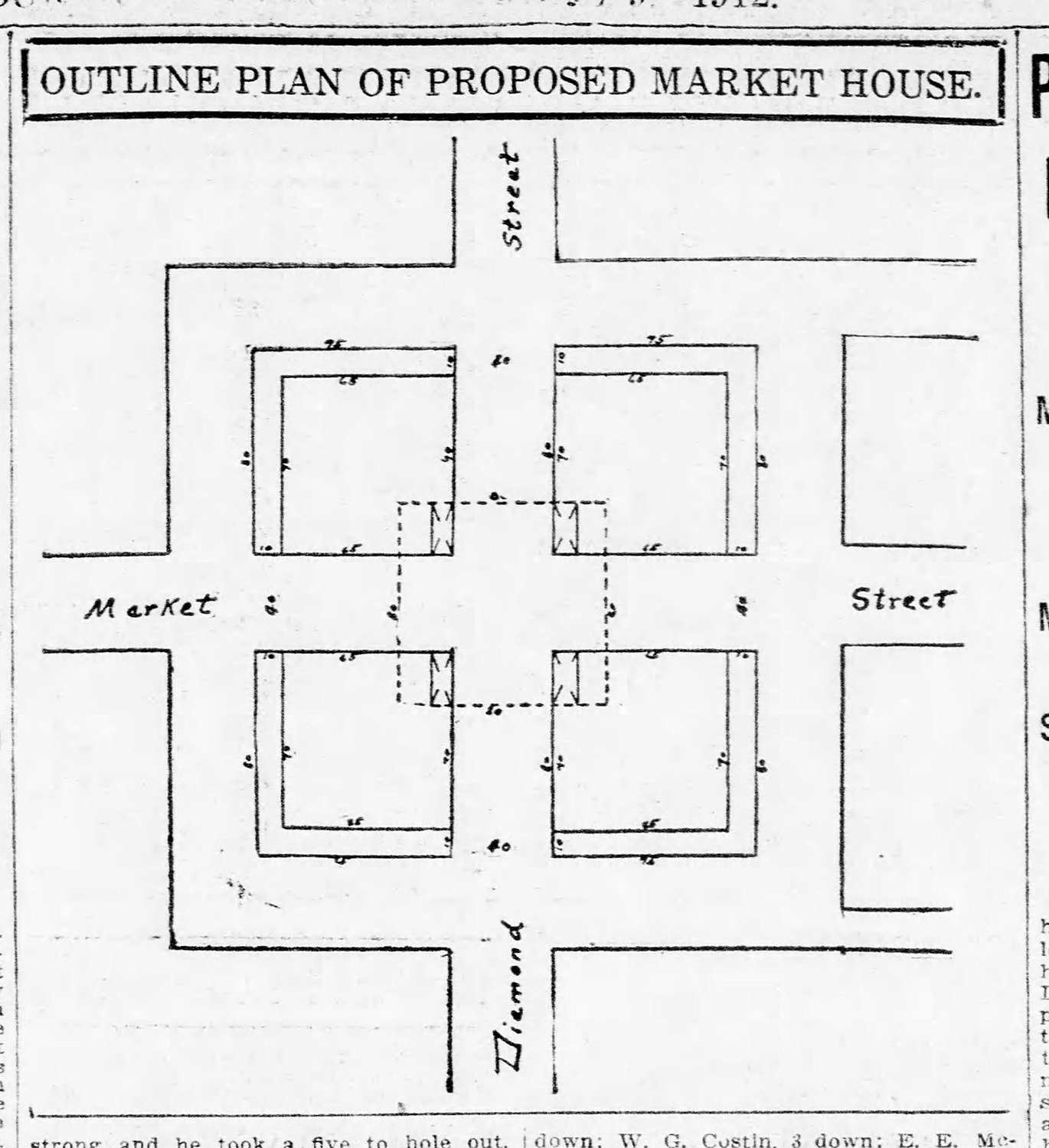

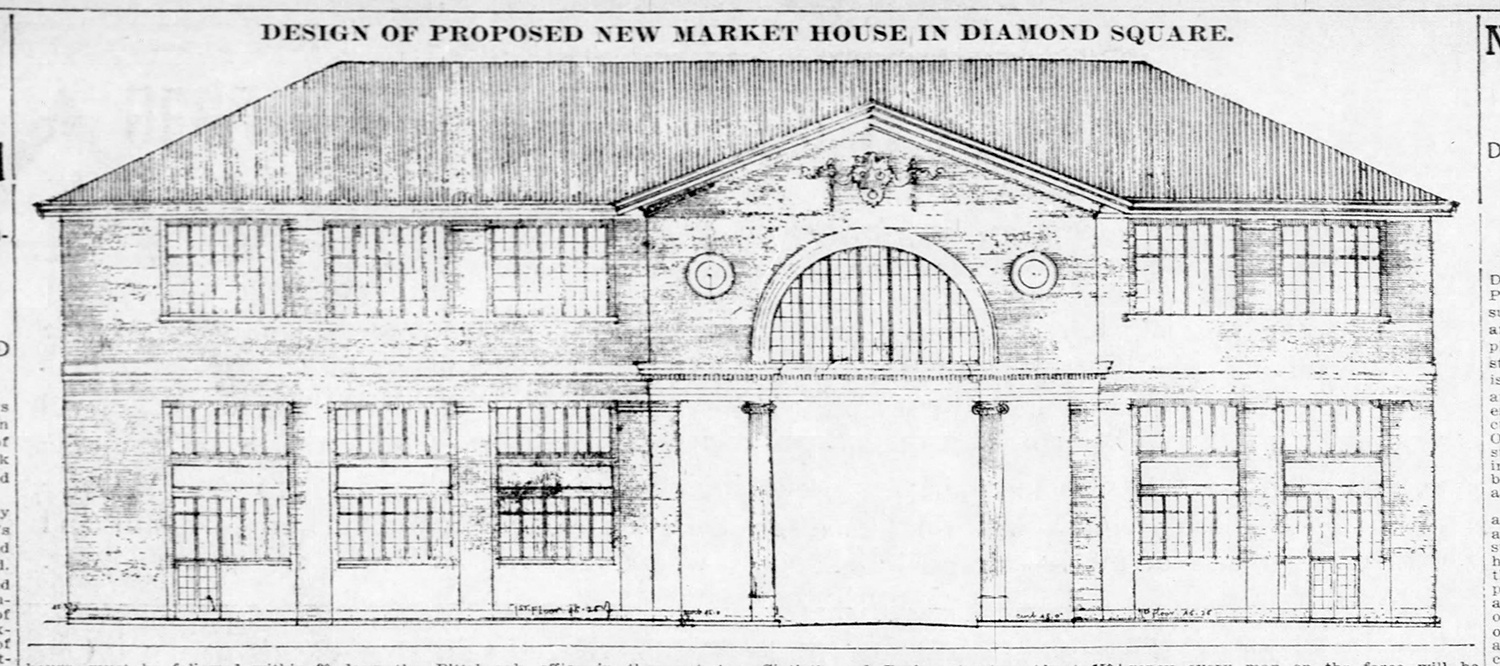

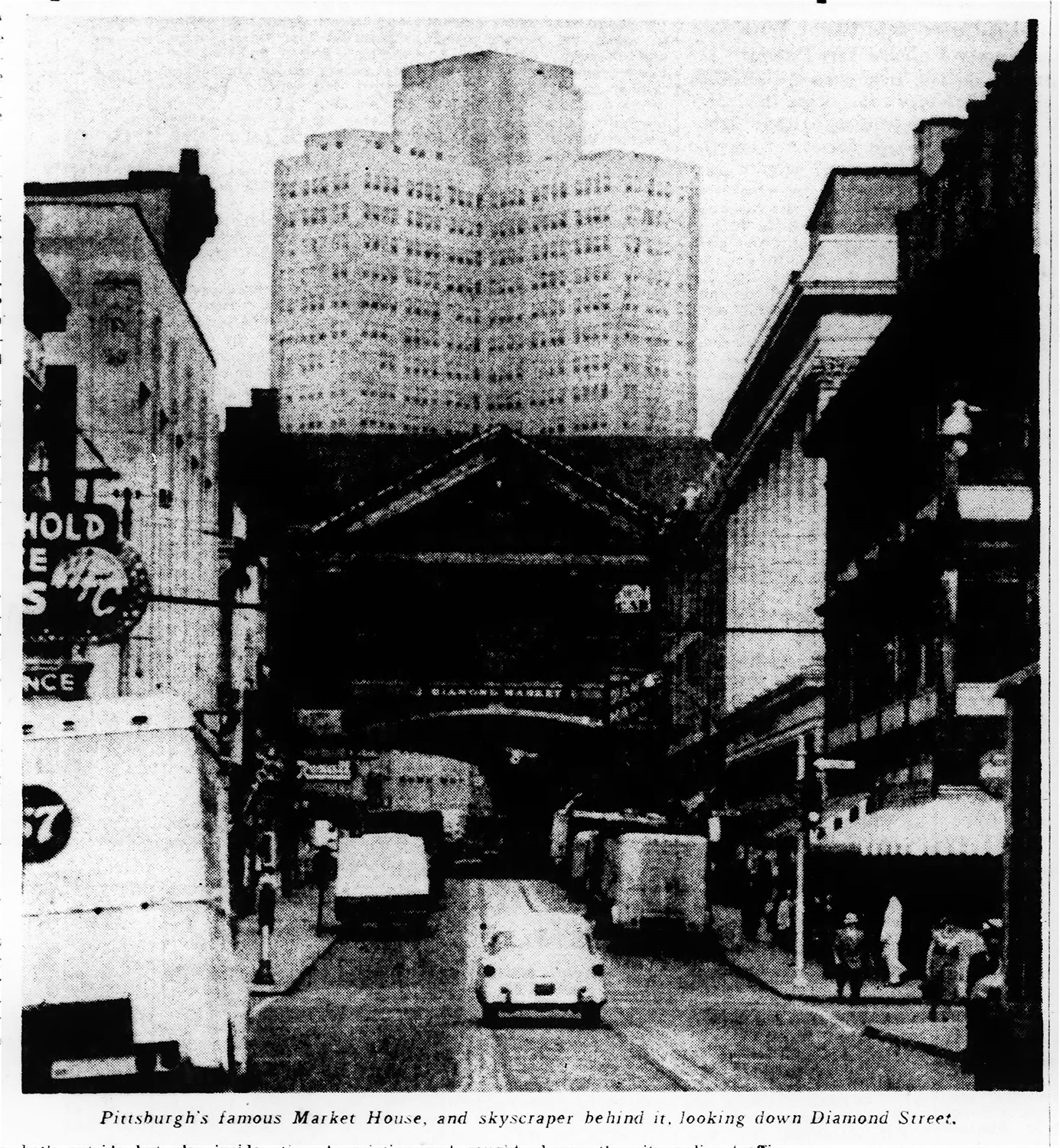

It was not supposed to end that way. When discussions for a new market began around 1908, the idea of a larger building garnered broad support. By 1911, city officials called it a “necessity.”[3] Downtown planners, still learning how to accommodate automobiles, celebrated the idea of creating more internal space by extending a multi-story building over a widened Diamond Street. The plans included a new mezzanine for cold storage and meat handling.[4]

Pittsburghers previewed the building in newspapers between 1911 and 1913. The east section opened in 1915. Vendors relocated there as work proceeded on the west section.[5] Mayor Joseph Armstrong officially dedicated the full market on Dec. 19, 1917. Newspapers reported that the building was “handsomely decorated.” In keeping with the patriotic spirit of a nation fighting World War I, marketmen pledged five percent of the day’s receipts to the American Red Cross.[6]

Changing Tastes and Times

Diamond Market served as a hub for many years, but its days were numbered from the start. Even as the market opened, the retail landscape around it was changing. In 1916, the first “self-serve” grocery store debuted in Memphis, Tenn.[7] The concept spread, and Pittsburgh businesses answered. Donahoe’s, originally a market vendor in the early 1900s, opened a grand “food department store” in 1923 near Diamond and Fifth Street, not far from Diamond Market.[8] At its height, the company operated about 30 grocery stores across the region, just one of many such examples.

After 1920, Prohibition also diminished the profits of market house merchants who regularly supplied the downtown saloons, a consumer base that disappeared. The stock crash of 1929 ushered in the Great Depression, further reducing the economic resources of the city and its residents. Charges of a bloated market payroll and corruption (widespread during Prohibition) plagued the space.

Who Pays the Bills?

Such challenges fed other tensions. Tax dollars funded market operations and low leasing fees failed to cover costs. By the 1920s, the city began seeking new ways to generate money for the space. In 1931, matters came to a head. Press headlines condemned the market’s terrible conditions. Images depicted vendors shielding their goods from ceiling leaks with canvas tents and buckets. The building carried a $25,000 deficit.[9] (About $430,000 in 2020.) Leasing the second floor to the roller-skating rink in 1934 took advantage of that pastime’s Depression-era craze to generate additional revenue.[10]

“William Penn’s Ghost”

By 1947, the city had enough and tried to sell the building to private operators. An ordinance passed to authorize the sale. Market vendors feared they would be kicked out and fought back in court. They argued that the land on which the market sat was given to Pittsburgh by the William Penn Estate in the 1780s for one purpose: to house a public market. They warned that negating such public use would cause ownership of the land to revert to Penn’s descendants.[11] The city seemed unmoved by the threat, which the local press dubbed “William Penn’s Ghost.” After battling two years in court, the vendors won. In 1949, Court of Common Pleas Judge James McNaugher ruled that since the city never owned the land on which the market sat, it had no right to sell the structure.[12]

The Final Cornice Falls

Diamond Market survived, but the tide had turned. By 1956, critics labeled it “the city’s sacred white elephant.”[13] Photos contrasted the market against the new Gateway Center skyscrapers looming behind it. When a piece of cornice fell off the building in December 1959 and hit Mrs. Mary Shelton of Forest Hills while she was Christmas shopping, it emphasized the structure’s poor condition and resurrected arguments that Diamond Market had to go.

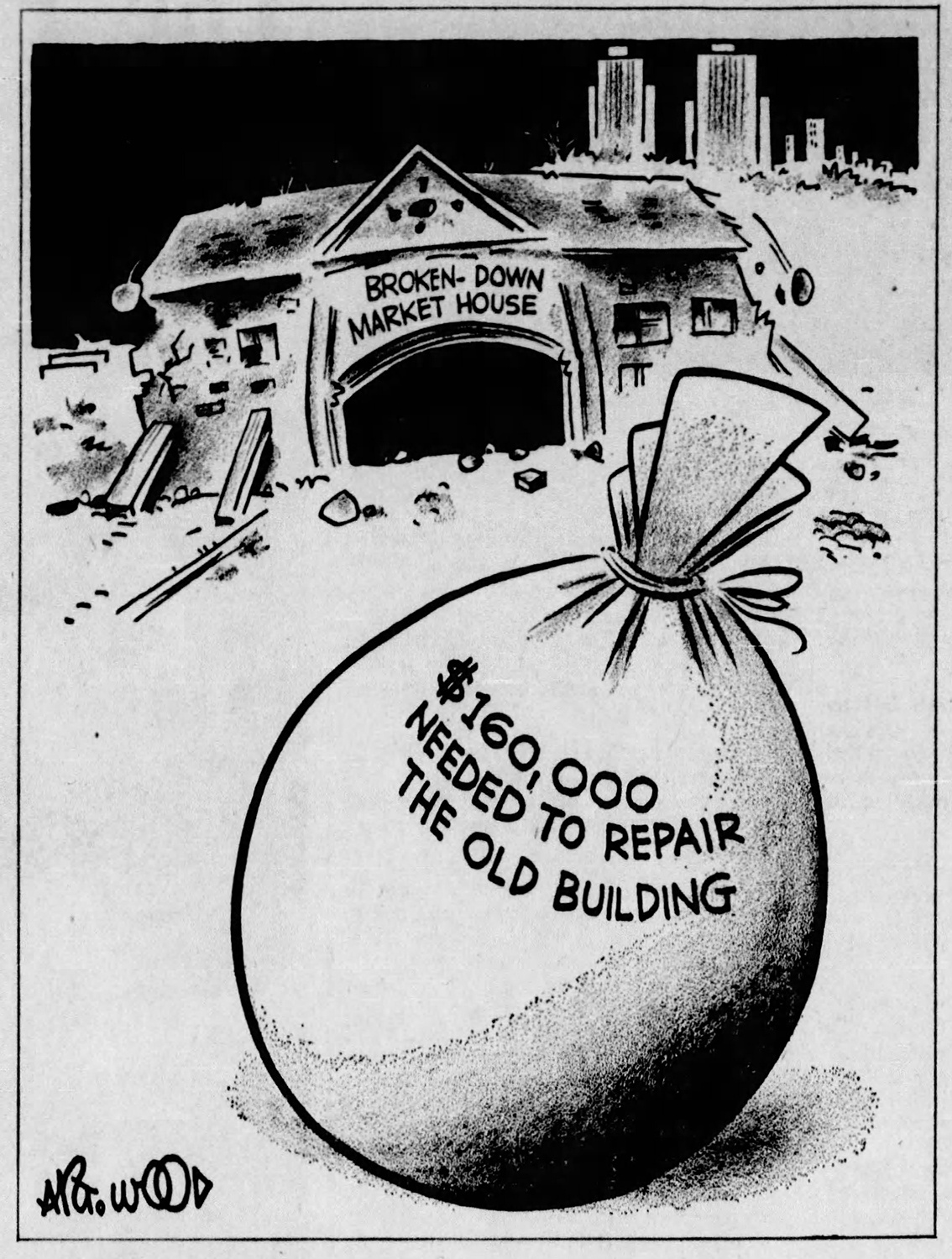

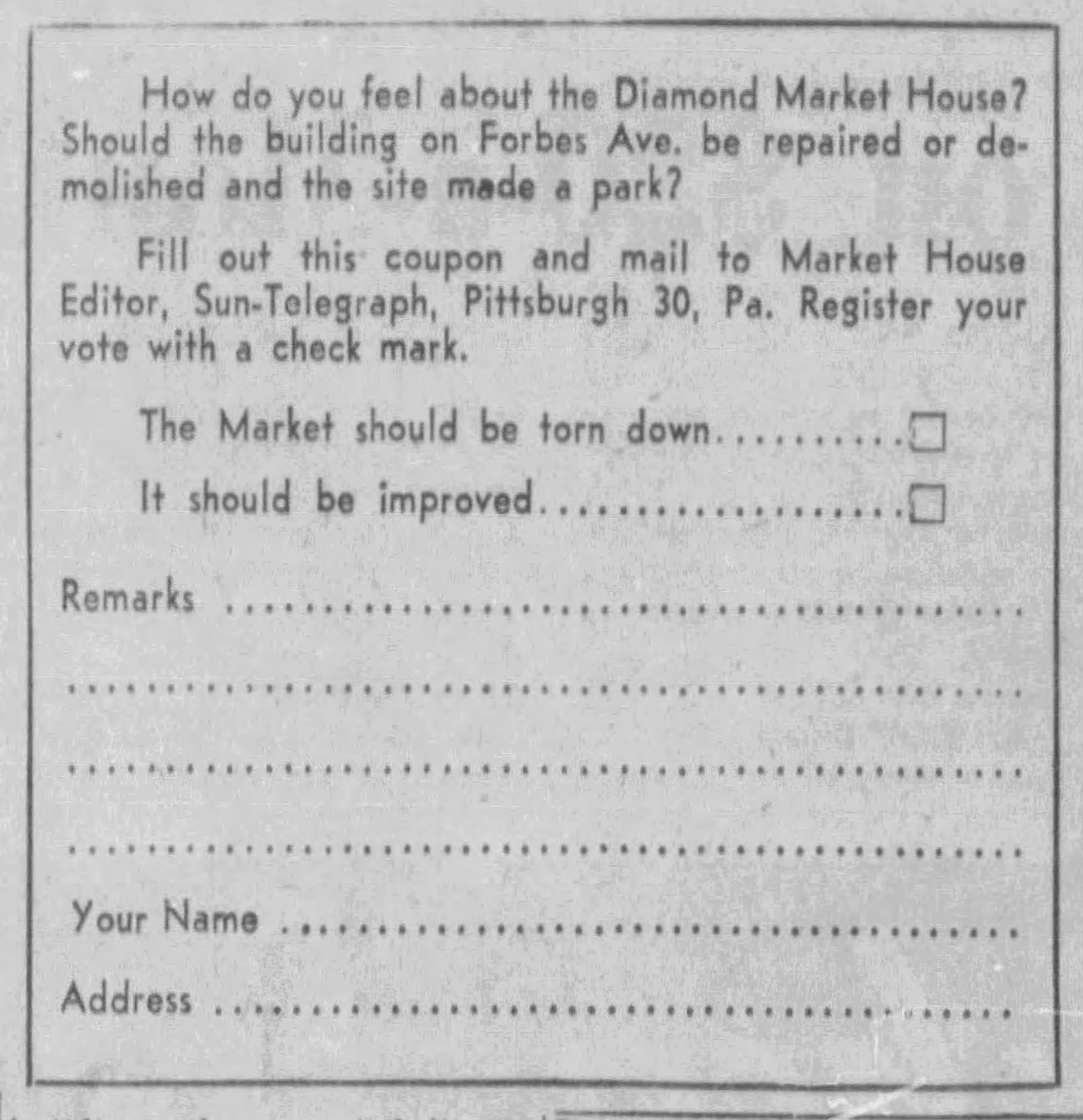

Longtime vendors rallied again to save their home. They offered to raise money for repairs estimated to cost around $160,000 dollars. The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph ran a campaign in March 1960 asking its readers, “Repair or Demolish? Vote Your Choice.” Most respondents wanted to save the building.[14] Some architectural planners also admired the old structure. One called it “picturesque as hell” and suggested turning it into a “honky tonk” (arcade).[15]

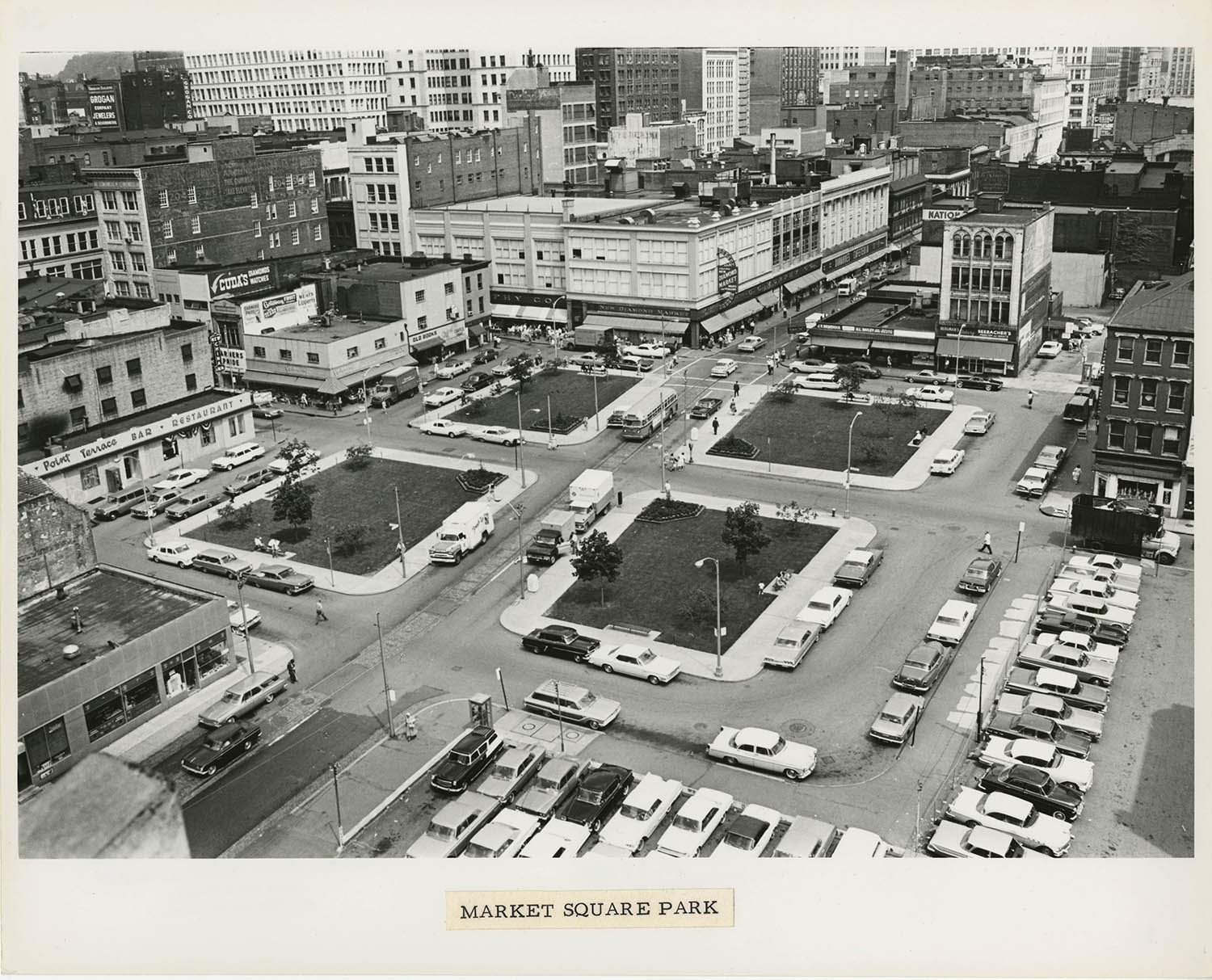

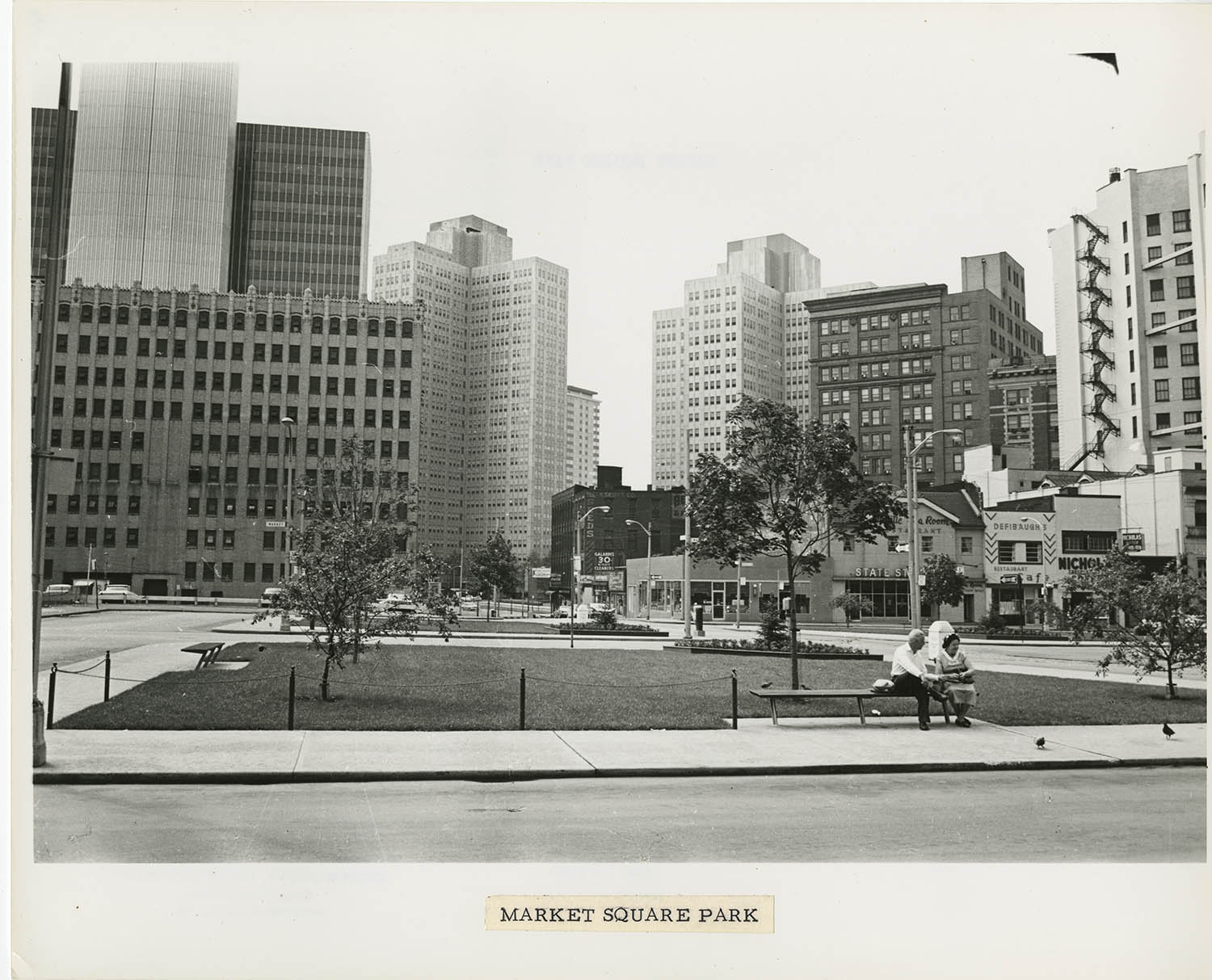

Debate ended when authorities discovered that the Market Vendors Association was six months behind in the rent.[16] On Sept. 28, 1960, the city announced that the market would be demolished and replaced with a park.[17] Existing leases granted vendors three final months, so shoppers enjoyed one last Christmas before the market closed for good at the end of business on Dec. 31, 1960.[18]

Originally slated for demolition in April 1961, the building got a brief reprieve when renegotiation of an urban renewal contract delayed work for a few months. But early on June 4, 1961, spectators watched as a crane and wrecking ball finally began tearing down Diamond Market, paving the way for the Market Square Park that we know today.

[1] In 1953, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), successfully fought to open the roller-skating rink to African American skaters: “The Good Work of CORE,” Pittsburgh Courier, Nov. 7, 1953.

[2] “Old Concrete Cornice Crumbles, hits Woman,” Pittsburgh Press, Dec. 16, 1959; “Stone Falls, Strikes Woman,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 17, 1959. Mrs. Shelton eventually sued the city over her injuries.

[3] “Councilman Proposes New Market House,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Aug. 5, 1911.

[4] “New Market House Plan Provides more Space,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, Dec. 12, 1913.

[5] “Section of Market Opens: Old Building Abandoned,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, Aug. 17, 1915.

[6] “New Market Houses open with Benefit for Red Cross,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 20, 1917.

[7] Kat Escher, “The Bizarre Story of Piggly Wiggly, the First Self-Serve Grocery Store,” SmithsonianMag.com, Sept. 16, 2017. Available online.

[8] “Donahoe’s New Food Store to be Thrown Open to Public Tuesday; Plant one of the Largest and most modern of its Kind in the World,” Pittsburgh Sunday Post, Jan. 21, 1923; Falck, Zachary, “Keystone Cuisine: Donahoe’s,” Western Pennsylvania History (Spring 2011), 14-15.

[9] “Mismanagement Charged at Diamond Market House,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, March 12, 1931.

[10] “Eddie Reynolds Takes Over New Roller Rink,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 21, 1934; Discussions about a roller rink began by 1932: “Market Lease Change Sought,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 30, 1932.

[11] “William Penn’s Ghost Haunts Plan of City to Sell Diamond Market,” Pittsburgh Press, June 17, 1947.

[12] “Court Rules City Can’t Sell Market House,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 12, 1949.

[13] “The City’s Sacred White Elephant,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 27, 1956.

[14] “Repair or Demolish? Vote Your Choice for Market’s Fate, Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, March 27, 1960; “Keep Diamond Market is Opinion of Most, Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, April 3, 1960.

[15] “Editor says ‘Honky Tonk’ Charm Lacking / Livelier Downtown Urged,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Feb. 2, 1960.

[16] Market vendors protested this assessment, saying that once the roller rink closed, they were not responsible for paying its portion of the lease. “Opposition to wrecking disappears,” Pittsburgh Press, Sept. 28, 1960.

[17] “Opposition,” Pittsburgh Press, Sept. 28, 1960.

[18] “Era Ends in Diamond Market Closing,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 1, 1961.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.