Remembering a hero’s return to the Mon Valley in the summer of 1944

Rumors about his arrival had swirled in the community for weeks. Some thought he would be home by May 30, but that date had come and gone. By the time the young man stepped off the train at McKeesport’s Baltimore and Ohio Railroad station around 2 a.m. on June 23, 1944, he hoped that he could quietly head to his destination in peace.

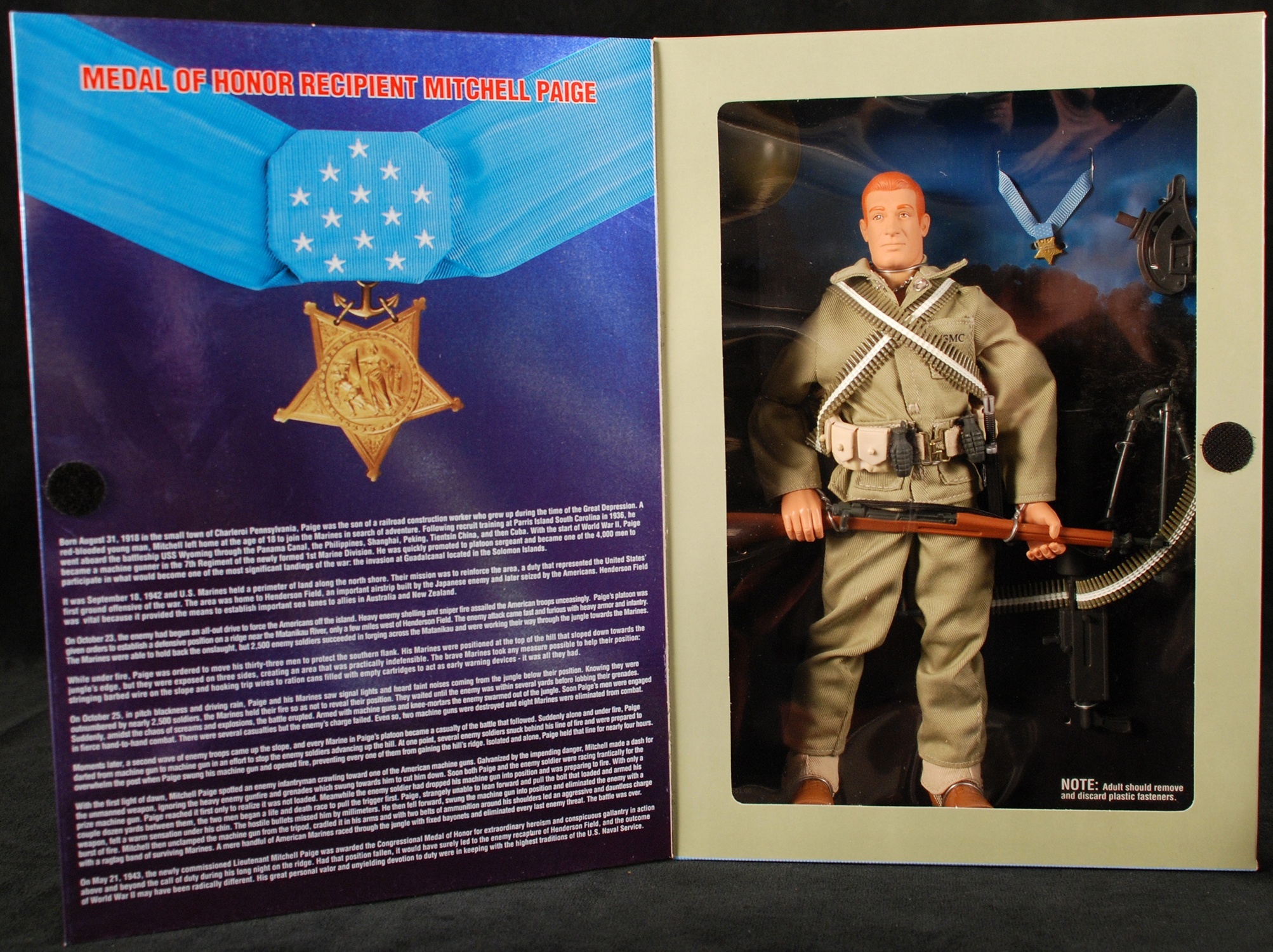

No such luck. A crowd of more than 1,000 people greeted Lieutenant Mitchell Paige, Allegheny County’s first World War II member of an elite fraternity: soldiers whose bravery in action had earned the Congressional Medal of Honor. Someone even brought a cake. Granted a 30-day leave, Paige returned to a region eager to celebrate the Battle of Guadalcanal heroics that had earned him the medal, an award Paige repeatedly vowed belonged not to him, but to the 33 other men who had fought alongside him. (You can hear Paige himself discuss the combat for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor in a video interview done before his death in 2003.)

Paige’s return to McKeesport and the Monongahela Valley in the summer of 1944 illustrated the delicate balancing act faced by veterans as they came home to a nation that wholeheartedly wanted to honor their service but had little notion of the reality they had left behind. For Paige, the whirlwind of activity started before he even crossed the Pennsylvania line. A Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter and photographer boarded Paige’s rail car in Akron, Ohio, eager to get pictures of the Lieutenant in his Pullman berth. “All I want to do is relax,” he said to the reporter, whose article appeared the same day Paige walked into the late-night (or early-morning) crowd in McKeesport.[1]

Arriving on a Friday, Paige got a few days of rest with his family before launching into a series of appearances, parades, and war bond drives. Mother Nature nearly upset some of those plans with a ferocious series of weekend tornadoes that ripped through parts of Western Pennsylvania and West Virginia, including McKeesport, Port Vue, West Liberty, Elizabeth, and other communities, killing 90 people and leaving hundreds injured.[2] But such was the impact of Paige’s story that plans merely shifted to accommodate and avoid the storm-damaged areas.

After spending Monday washing and ironing his own shirts, insisting that he knew best how to ensure the proper military crease, Paige kicked off the visit Tuesday morning with a grand parade in McKeesport and an extended tour of the Monongahela Valley, stopping at seemingly every community in the region before finally attending a grand banquet on Wednesday evening with 750 people at the Alpine Hotel.

For the next few weeks, he was seemingly everywhere. He joined a fellow Medal of Honor recipient from World War I, Sterling Morelock, meeting convalescents at a veterans’ hospital in Aspinwall. He ate dinner with community officials at multiple locales, received gifts from the Serb National Federation, and sold “nearly a million and a half dollars” of war bonds.[3] He volunteered to help with the western Pennsylvania milkweed drive, an effort to collect the silky strands used to replace kapok as a filling for naval life preservers. He also made a quick trip to Chicago to appear in a live radio program. By the time Paige was contemplating the end of his leave in early August, he estimated that he had gotten about three hours of sleep a night since arriving back in western Pennsylvania.

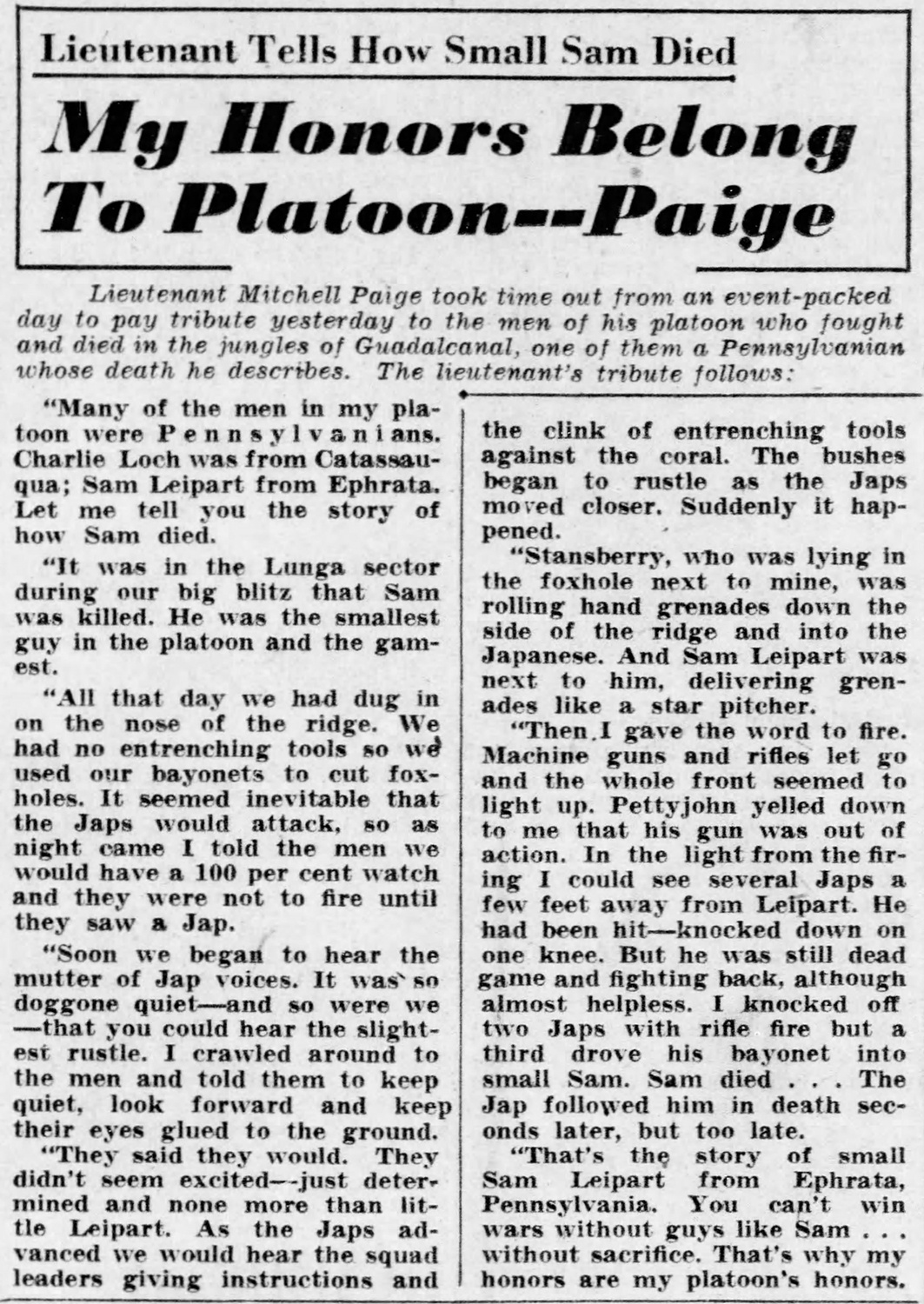

Even in the overtly celebratory media coverage of the visit, there were moments when the more somber nature of Paige’s experience emerged. One reporter described his manner answering a barrage of questions as “diffident . . . as he felt he really shouldn’t be telling these things.”[4] Paige said that his only regret about the furlough was that he couldn’t bring “all my boys along.”[5] Newspapers published President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s words describing Paige’s actions in Guadalcanal; Paige himself seemed reluctant to discuss them. (Many years later, he remembered that it took at least 15 years before he felt comfortable talking about what happened that day.) He did, on at least one occasion, speak directly about the loss of members of his platoon, repeating his assertions that his honors were not his, but belonged to his men. He even got the Post-Gazette to print his account of the death of one of his Pennsylvania boys in the jungles of Guadalcanal, Sam Leipart of Ephrata. At the end of the piece, Paige observed, “you can’t win wars without guys like Sam . . . without sacrifice. That’s why my honors are the platoon’s honors.”[6]

In the din of the next few days and weeks, for most readers those words probably receded behind the wave of other war news, including Paige’s own whirlwind of activity. But for Paige, and similar to the sentiments of countless other combat veterans who would echo the same thing through the years, it was possibly one of the most meaningful moments of coverage he was able to garner during the visit.

As the Heinz History Center focuses this week’s “History’s Helpers” stories on the value of bravery in honor of Memorial Day, it’s worth recalling again the story of veterans such as Paige, looking beyond the public commendations to the real sacrifices that their stories embody.

For further information:

For more about the sacrifice of servicemen during World War II, revisit this Making History blog post featuring the words of four young men killed in duty: The Last Letters (2018).

[1] Vincent Johnson, “Lieutenant Paige Counts the Minutes,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 23, 1944.

[2] See, for example: “90 Dead, Over 600 injured as Tornado Rips District,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 24, 1944.

[3] “Marine Hero Paige Joins Milkweed Drive,” Pittsburgh Sun Telegraph, August 6, 1944.

[4] Maxine Garrison, “Pacific Hero makes Gallant One-man Stand Against Neighbors’ Barrage of Questions,” The Pittsburgh Press, June 23, 1944.

[5] Johnson, “Paige Counts,” 1944.

[6] Lieutenant tells how Small Sam died; My Honors belong to Platoon—Paige,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 24, 1944.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.