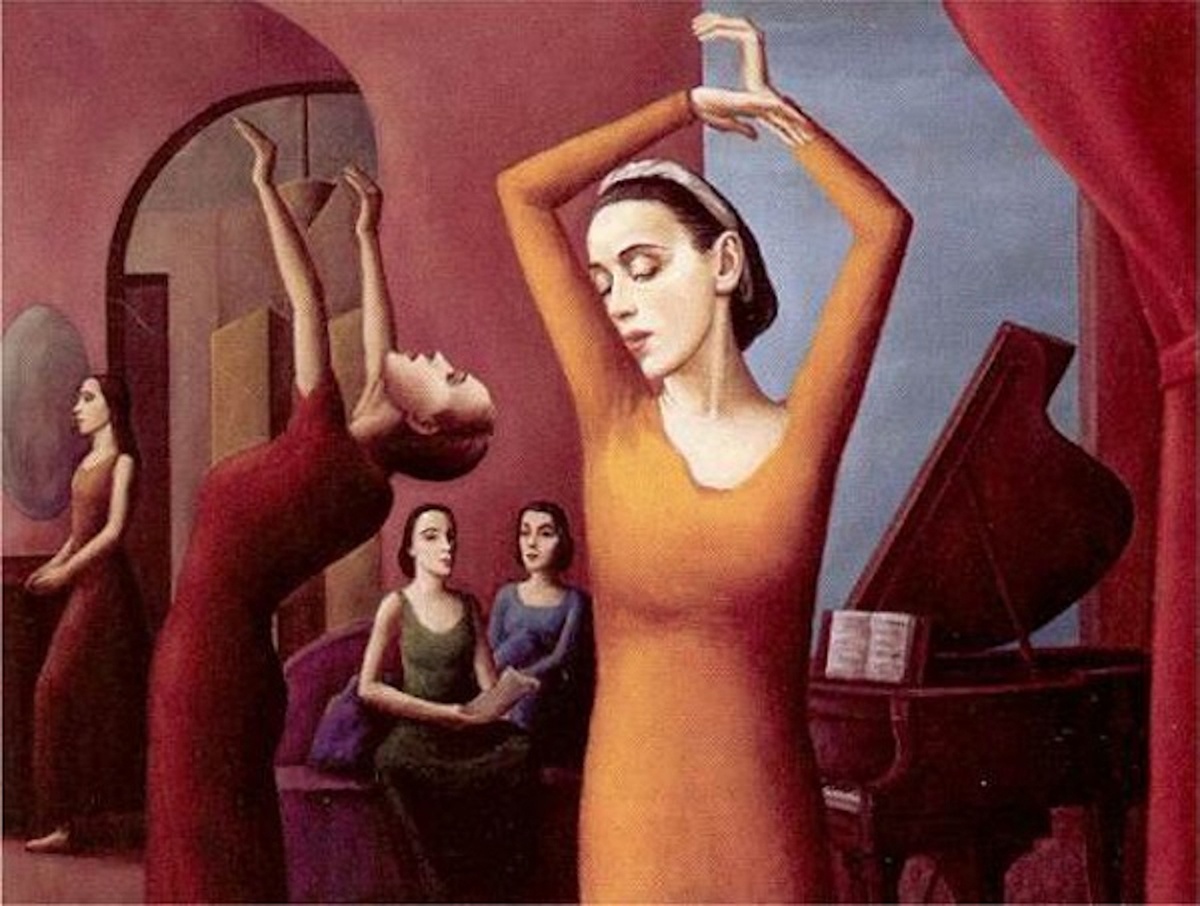

Inspiration takes many forms. American artist Paul Meltsner was fascinated by modern dancer and Allegheny City native Martha Graham. His oil portrait from 1938, currently on display in the Heinz History Center’s Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh: Works from the National Portrait Gallery, was one of at least seven images of Graham that he created during the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Meltsner, recognized for his WPA (Works Progress Administration) works such as post office murals and prints, focused on a search for “Americanism.” To him, Graham represented a pioneer, a cultural innovator pushing the vanguard in a new vocabulary for dance. Her choreography, driven by the philosophy that movement expressed one’s innermost emotions and that modern dance needed to reflect the “nervous, sharp and zig zag” energy of modern life, broke artistic barriers.[1] In fact, Melstner’s paintings captured Graham at just the moment in the late 1930s when her efforts to establish a new vision for modern dance finally began to gain wider acceptance. During this same period, Graham’s work also inspired another kind of following much closer to home. This connection led to her first return appearance in Pittsburgh with her modern dance troupe in 1937.

Lighting a spark in Pittsburgh

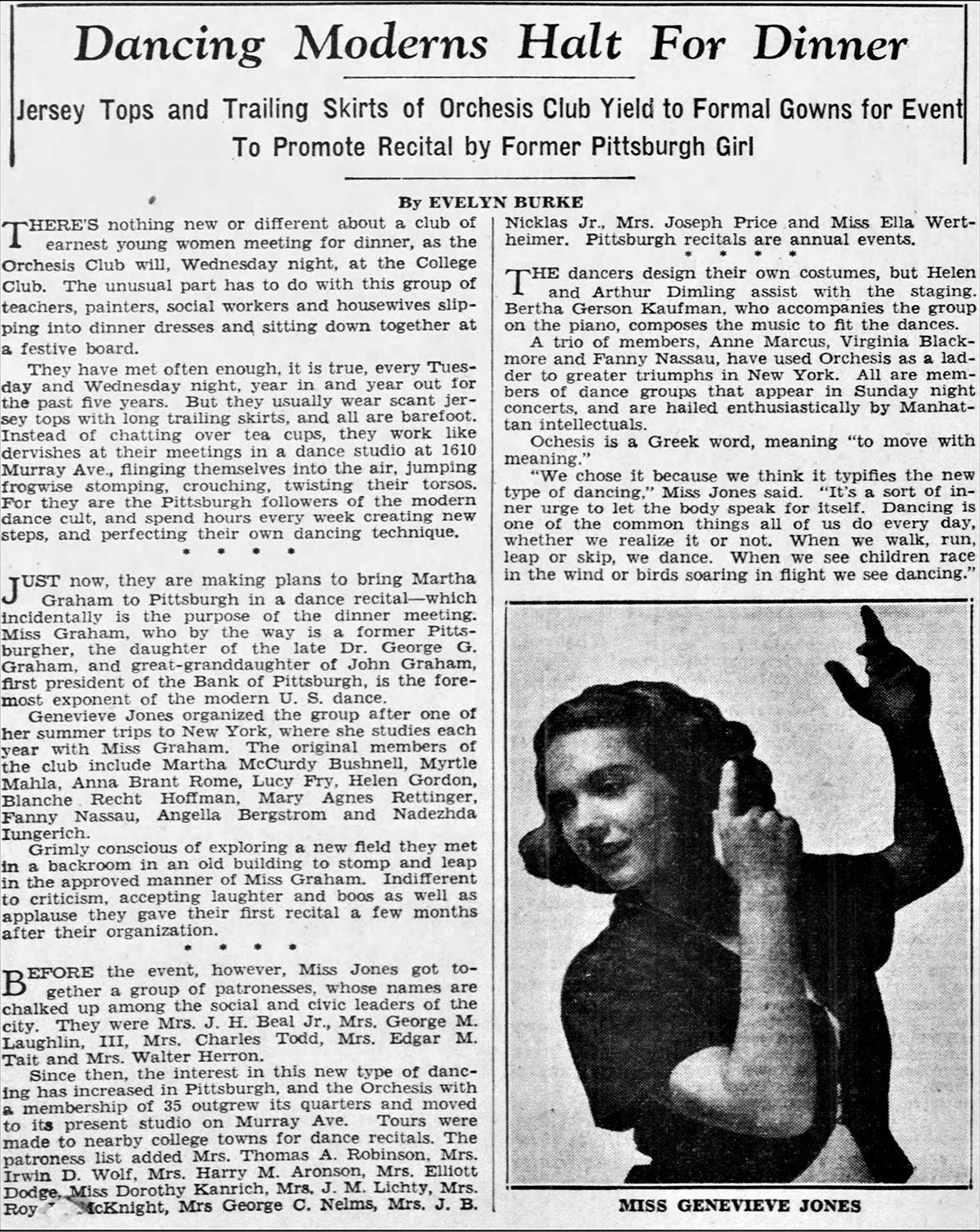

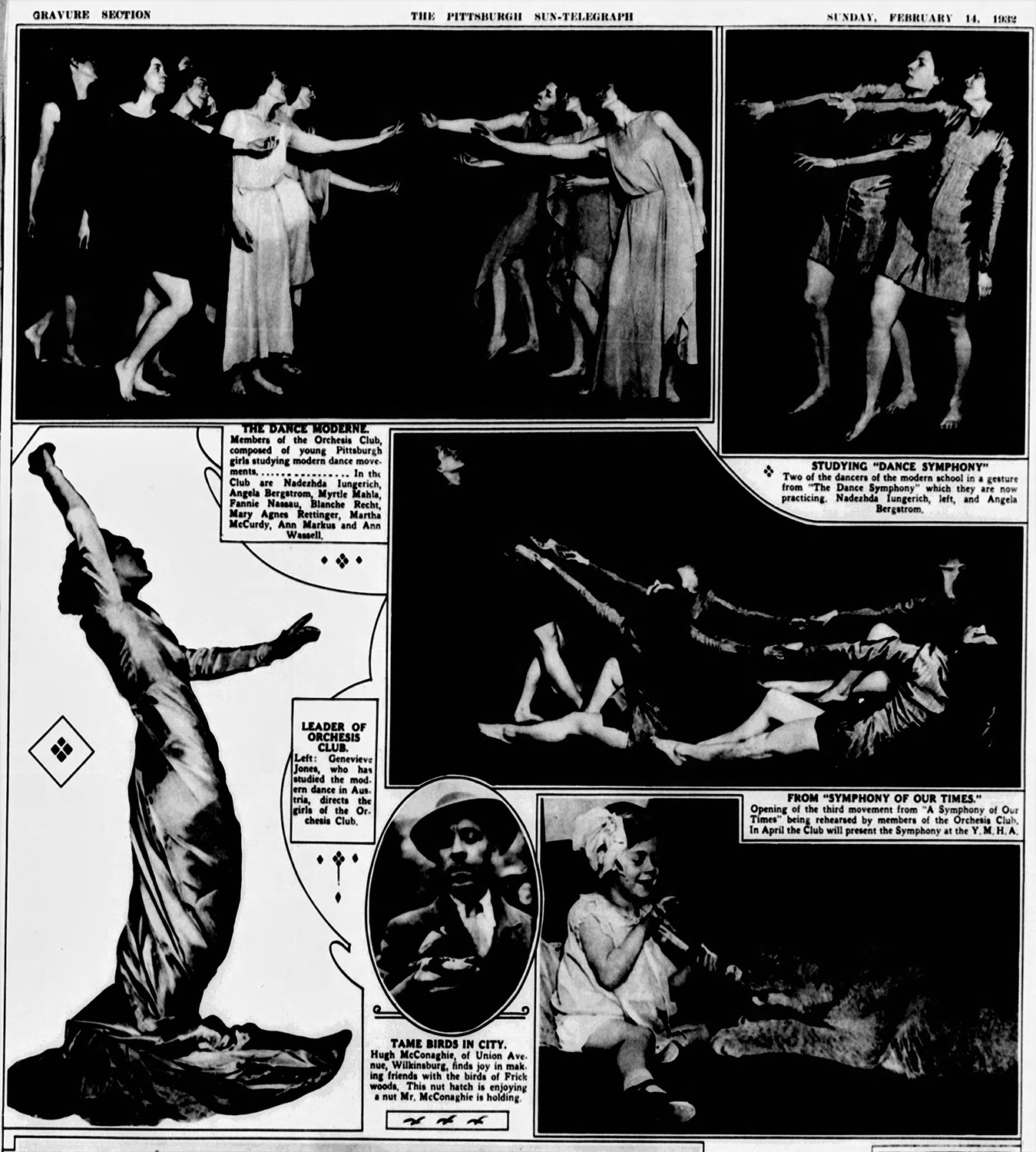

When Graham began offering modern dance recitals in the late 1920s, not everyone knew what to make of her or her work. Some people rejected it outright. She struggled to make a living, residing in an apartment that some reported was nearly unfurnished. She earned money by offering dance classes, and attracted a cohort of enthusiastic students, believers who stuck with Graham’s inspiration for the rest of their lives. One of those was Genevieve Jones of Pittsburgh, who studied multiple summers with Graham in New York City. Jones came back to her hometown to start the Orchesis Club, a modern dance club described by the Pittsburgh Press as a group of “teachers, painters, social workers and housewives” who were “followers of the modern dance cult.”[2] Starting in the early 1930s, Orchesis members studied and performed their own modern dance routines, garnering notice in the local press. Jones earned a reputation as the woman who introduced Pittsburgh to modern dance.

In 1937, the Orchesis Club spearheaded efforts to bring Graham and her modern dance troop back to the place of her birth. The timing was perfect. During 1936 and 1937, reception to Graham’s work was on the rise. She appeared in 42 out-of-town recitals across the country in addition to her 10 New York City performances. In April 1937 she finally arrived in Pittsburgh. The Orchesis Club welcomed her on April 29 with a tea hosted at their Murray Avenue dance studio. On Friday, April 30, 1937, Graham performed at the Carnegie Music Hall along with four of her dancers.

Accounts of local reaction to the performance vary. While the audience in attendance reportedly gave Graham “vigorous applause” and an ovation at the end, later stories suggest that only 500 out of a possible 2,000 tickets to the performance sold.[3] If so, it was in keeping with the gradual nature of modern dance’s acceptance across the United States outside the urban cultural centers of the coasts. Just as with modern art, it took time for people to adjust their expectations and broaden their definition of what the art form could offer. In one story about a press clipping sent to Graham as late as 1946, a reviewer from central Wisconsin noted that “Dick Thickens enjoyed himself because he had a flashlight and a copy of Reader’s Digest in his pocket”[4] The statement reflected another reality of Graham’s audience: men were slower to come around than women. In the same article that recounted the flashlight-wielding Mr. Thickens, the writer felt obliged to acknowledge that the percentage of men in Graham’s audiences had finally “increased perceptibly” by the later 1940s.[5]

A Repeat Engagement

Fortunately, Graham’s star kept rising. Audiences learned to understand and appreciate her artistry. Pittsburgh welcomed her back again in February 1947. Once more, Genevieve Jones, who now operated her own dance studio, spearheaded the event. Graham and company performed three works, including her legendary composition “Appalachian Spring,” with music commissioned from Aaron Copland. By this time, she was a major celebrity and a much larger venue was needed. Instead of the Carnegie Music Hall, she performed for an enthusiastic crowd at the Syria Mosque, with nearly twice the capacity. For Graham, whose works were adjudged to be “stunning” by The Pittsburgh Press, it had to be a satisfying evening.[6] Genevieve Jones probably felt vindicated as well.

Learn More

Angelica Gibbs, “The Absolute Frontier,” The New Yorker, December 27, 1947.

A good overview of Graham’s life and career can be found on the website of the Martha Graham Dance Company.

A nice selection of photographs from the archives of the Martha Graham Dance Company is featured in a Google Arts and culture exhibition that was curated by Pittsburgh area native and Graham Dance Company member Oliver Tobin.

To see Martha Graham in Motion

A brief clip of her work in the important early composition “Lamentation” (1930).

A rare early film of Graham and company performing “Appalachian Spring,” c. 1940, is offered through this link posted by the Martha Graham Dance Company (38 minutes).

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center and lead curator on the Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh exhibition.

Watch for more!

[1] Angelica Gibbs, “The Absolute Frontier,” The New Yorker, December 27, 1947

[2] Evelyn Burke, “Dancing Moderns Halt for Dinner,” The Pittsburgh Press, October 11, 1936.

[3] Ralph Lewando, “Graham Dancers Impressive at Modern Recital,” The Pittsburgh Press, May 1, 1937; Milan Simonich, “Genevieve Jones, Introduced Pittsburgh to Modern Dance,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 1, 1998.

[4] Gibbs, “Absolute Frontier,” 1947.

[5] Gibbs, “Absolute Frontier,” 1947.

[6] Ralph Lewando, “Dancers give Fine Program,” The Pittsburgh Press, February 13, 1947.