Lunar New Year, celebrated by people from East and Southeast Asia, marks the beginning of the new year. Based on the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar, it begins with the first new moon of the year, which usually falls in late January or early February. The origins of the holiday date back thousands of years and traditions include the honoring of deities, one’s ancestors and elders, and the family.

In recognition of this year’s observance, Shirley Yee has shared a reflection on what the Chinese New Year has meant to her throughout her life.

Arriving as a child immigrant during the Depression years, Shirley’s father Yuen Yee was a leader for the Chinese community of Pittsburgh and the unofficial Mayor of Chinatown. He served the community through the mid-1980s by supporting newcomers with bilingual translation, immigration matters, caregiving for elders, business advising, and public outreach with the local media. Shirley has preserved artifacts of her father’s life and compiled his handwritten memoirs that tell the triumphs and tribulations of early Chinese settlers in a once-vibrant urban Pittsburgh neighborhood. Since Yuen passed away at age 82 in 2008, Shirley, has chronicled the story of her father’s life and has recently donated Yee family archival materials and artifacts with the Heinz History Center to be preserved for perpetuity.

On celebrating Chinese New Year, Shirley shares:

“The Chinese New Year was my mother’s favorite holiday, and she fully embraced and celebrated its significance and traditions in my 1960s childhood memories.

The preparation began days earlier with a thorough housecleaning, then followed by a focus on food: the preparation, the buying, the freshness, the symbolism, the color, and finally, the full-on feasting.

Tangerines, preferred with green leaves attached on the stem, were displayed throughout our home, with a few red and gold paper decorations.

With many folk beliefs based on homonyms, my mother prepared foods that sounded like auspicious expressions. The “lucky” foods on the holiday dinner table included glass rice noodles for Longevity, roast pork for good fortune, oysters (sounds like the word “good”), plump dumplings, vibrant green vegetables, ending with a soup (bird’s nest or shark’s fin, with hair-like mushrooms, woodsy herbs, water chestnuts, and gingko nuts). For holiday snacks, Mom made sweets: sweet potato balls filled with soybean paste or a fine nuts mix, a muffin-tin sized rice flour pudding, and a layered gelatinous taffy studded with red dates.

Before the festive meal, children were gifted with “lucky” red envelopes with money, cash or coins, and a wish for Prosperity and Longevity. We greeted each other with “Gung Hee Fat Choi” meaning Best Wishes for Good Fortune.

My mother had strict rules for the holiday: no conversation about death, don’t wash your hair, don’t wear white or black, eat “lucky” foods, no broom sweeping, avoid the number 4 because the word sounded like Death, and my personal favorite: don’t drop your chopstick at the dinner table (dropping BOTH chopsticks was worse). The taboos were numerous, and it was not an especially fun holiday for me, except for the appearance of the lucky red envelopes.

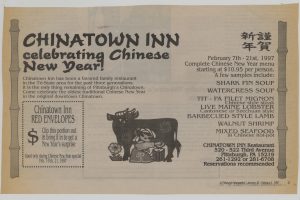

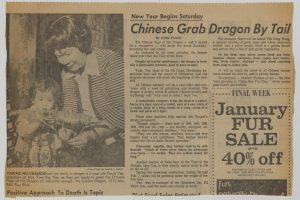

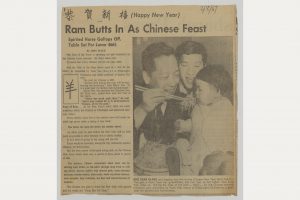

Outside the home, as the unofficial Mayor of Chinatown, my father eagerly responded to the newspaper media journalists, describing the significance of the Lunar New Year festivities and the traditions. My siblings and I were often featured in the newspaper stories about the holiday, participating with Dad in the photoshoot. As we got older and aged out, he would ask other Chinese families (he knew them all) with younger kids to participate. At the Chinatown Inn, he created a special menu to celebrate the holiday with traditional and popular dishes. As the biggest fan of the Chinese community, he followed the activities of all the local Chinese restaurant workers and their families, clipping newspaper advertisements of their business and achievements for his scrapbooks.

The Lunar New Year will always hold a special place in my adult and Americanized heart as I fondly remember my immigrant parents who shared their Chinese cultural traditions and dreams with Us, the children of Yuen and Betty Yee.”

— Shirley Yee, 2024

About the Author

Shirley Yee has donated her family’s archival materials and artifacts to the Heinz History Center. Shirley teaches Visual Interaction Design at Carnegie Mellon University.