In the early 1920s, two immigration acts, the Emergency Quota Act in 1921 and the Johnson-Reed Act in 1924 (later known as the Immigration Act of 1924), placed quotas on immigrants entering the United States. Quota numbers were determined by the National Origins Formula, which restricted the number of incoming migrants based on ethnic populations in 1910 and 1890, respectively. This policy was in use from 1921 through 1965, instituted to curtail the high number of unskilled laborers immigrating from Southern and Eastern Europe.

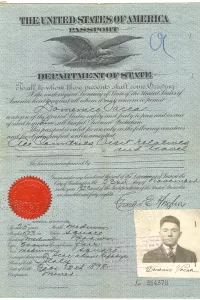

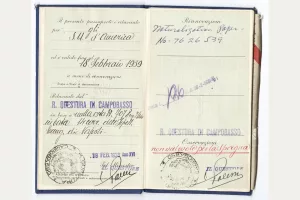

First generation Italian American Carmen Vacca was born in Italy in 1930. His father, Domenico Vacca, entered the United States in 1916 and naturalized as an American citizen five years later in Pittsburgh’s U.S. District Court on Nov. 29, 1921. Like many naturalized European men, he returned to Italy from time to time and, on one of these return visits, he married Amelia Acaro in February 1924. While Domenico lived and worked in the United States, his wife and two sons remained in Castelpetroso, Italy; this scenario was not uncommon during the interwar years. Because Domenico had American citizenship, his Italian-born children gained U.S. citizenship automatically through the process of acquisition; it also meant that his wife was eligible to immigrate to the United States as a non-quota immigrant, which she did in 1938.

After more than 10 years in the United States, Carmen joined the United States Army Reserves in 1949 at the encouragement of his older brother, Nicholas, who was serving in the U.S. military. Around the same time that Carmen joined the Armed Forces, his mother began proceedings to get her U.S. citizenship. During her interview, she mentioned that her husband reluctantly served a year in the Italian Army on one of his sojourns in Italy after his American naturalization. At the time of Domenico’s service, Italian law dictated that all Italian-born men, even those who naturalized and resided in other countries, were subject to military service. Sadly, Amelia’s honesty set into motion deportation proceedings for the Vacca family.

Warrants issued for Domenico, Amelia, Nicholas, and Carmen on Nov. 15, 1951, cited the Immigration Act of 1924 and contended that Domenico expatriated himself while serving in the Italian Army. The charge of expatriation meant that sons Nicholas and Carmen never inherited U.S. citizenship and Amelia immigrated under the wrong category of visa.

Carmen recalled the frustration he experienced at his mother’s hearing in his oral history interview, stating: “We had a hearing at the Federal Courthouse, and my mom didn’t speak English very well, so they got an interpreter for her. And they would ask her questions, and the interpreter would sound of with something entirely different, and I jumped up and said, “She’s not saying what my mom said!” Well, the judge told me to sit down. I sat down. A couple questions later the same thing. And I jumped up and I told him the same thing. He said, “You’re in contempt of court. The next outburst, I’m going to put you in jail.” I said, “Go ahead, put me in jail.” I was on my way to Korea. So that was the end of that. Vacca family lawyer, Frank J. Zappala, successfully argued that Domenico’s service in the Italian Army “was taken under legal compulsion amounting to duress.”1

This was proven in part because of Domenico’s continued appeals to the American Consul in 1923 and 1924 yielded documentation verifying a representative of the United States was not only aware of the situation but sanctioned his foreign service as it obeyed Italian law. On Nov. 15, 1953, it was concluded that “under Section 13 and 14 of the Immigration Act of 1924, the respondent is not subject to deportation on the ground that at the time of entry he was a quota immigrant and was not in possession of an unexpired quota immigration visa.” 2 By the time the Vacca family received judgement on their American citizenship, Carmen’s Army Reserves unit had been drafted into the Korean War. His wife Rosemary wrote regularly to keep him abreast on the status of his case.

Despite the legal issues surrounding their American citizenship, the Vacca family lived as good citizens before and after the ruling. Domenico was issued a new Certificate of Naturalization on Sept. 27, 1955, which acknowledged his original naturalization date in 1921, and his wife Amelia officially became a U.S. citizen on Feb. 17, 1956. Italian-born brothers Nicholas and Carmen both served in the U.S. Army Reserves. Carmen fought in Korea for 18 months, overseeing communications for the 58th Ordinance Company; he was discharged from the U.S. Army Reserves in 1964 as a Sergeant First Class after his unit relocated to West Virginia in 1964.

Nicholas entered the real estate business after he left the military under a medical discharge; one of his specialties became executing mortgage loans from the Veterans Administration. Of the American-born Vacca children, Mario and Daniel Joseph, the latter served in the U.S. Navy and was stationed on a ship during the blockage of Cuba in 1962. The plight of the Vacca family is exemplary, not only because they persevered together throughout their citizenship struggle, but their dedication to their chosen homeland never wavered.

About the Author

Melissa E. Marinaro is the director of the Italian American Program at the Heinz History Center.