Tapping into Pittsburgh’s WWII Past

Rogue National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden made headlines in 2013 when he exposed that the agency’s secret phone and internet surveillance program included tracking millions of Americans. But what Snowden revealed was nothing new. Objects on display at the History Center spotlight how the dilemma of individual privacy versus national security played out in Pittsburgh during World War II.

At first glance, these artifacts—including a Western Electric telephone test handset, a lineman’s belt, and climbing spurs—look like equipment used by any telephone repairman from the 1940s. But their owner didn’t work for the phone company. He worked for the FBI.

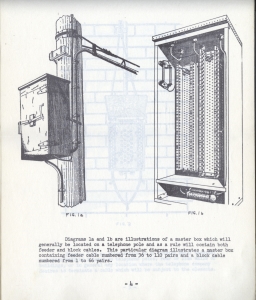

Agent John F. Leahy investigated cases of wartime industrial sabotage in Pittsburgh and eventually settled here. The dial-in handset, an old-style telephone receiver attached to wires ending in alligator hooks, could tap directly into a phone box or phone line to monitor conversations. Photos from Leahy’s family show him in action, scaling a tree and wearing equipment featured in the We Can Do It! WWII exhibition. A page from Leahy’s FBI manual illustrates how to identify a telephone master box.

The catch? On paper, Leahy’s actions were partly illegal. The 1934 Federal Communications Act outlawed the use of information gathered via phone taps following legal challenges from an infamous Prohibition wiretapping case. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld this ruling in 1939.

But in 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt issued a secret executive order authorizing wiretapping for “subversives” and spies. Pittsburgh, a key industrial center already deeply engaged in war work, was considered a prime sabotage target. The city’s large immigrant and resident alien population didn’t help. Fear ran especially high during the war’s early years. In June 1942, a German sabotage mission fell apart after reaching American shores. Nazi targets reputedly included Altoona’s Horseshoe Curve, multiple Alcoa plants across the country, and the Curtiss-Wright propeller factory in Beaver, Pa. True or not, such rumors fueled a climate that legitimized the FBI’s actions, and J. Edgar Hoover needed little excuse to take President Roosevelt’s order as far as it would go.

The fear also shaped popular culture. Pittsburgh audiences watched a fictionalized account of a sabotage plot unravel on the big screen at the Senator movie theater in May 1943 when “They Came to Blow Up America” played here. Although the New York Times dismissed the film as “pulpy drama,” it’s fun to wonder what FBI Agent John Leahy would have thought of it.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center and the lead curator for the We Can Do It! WWII exhibition.