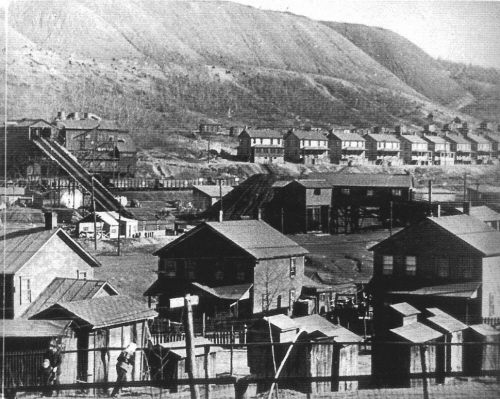

Wandering the aisles of the Visible Storage exhibition at the Heinz History Center, a visitor can catch a glimpse into an almost-forgotten period of coal mining culture.

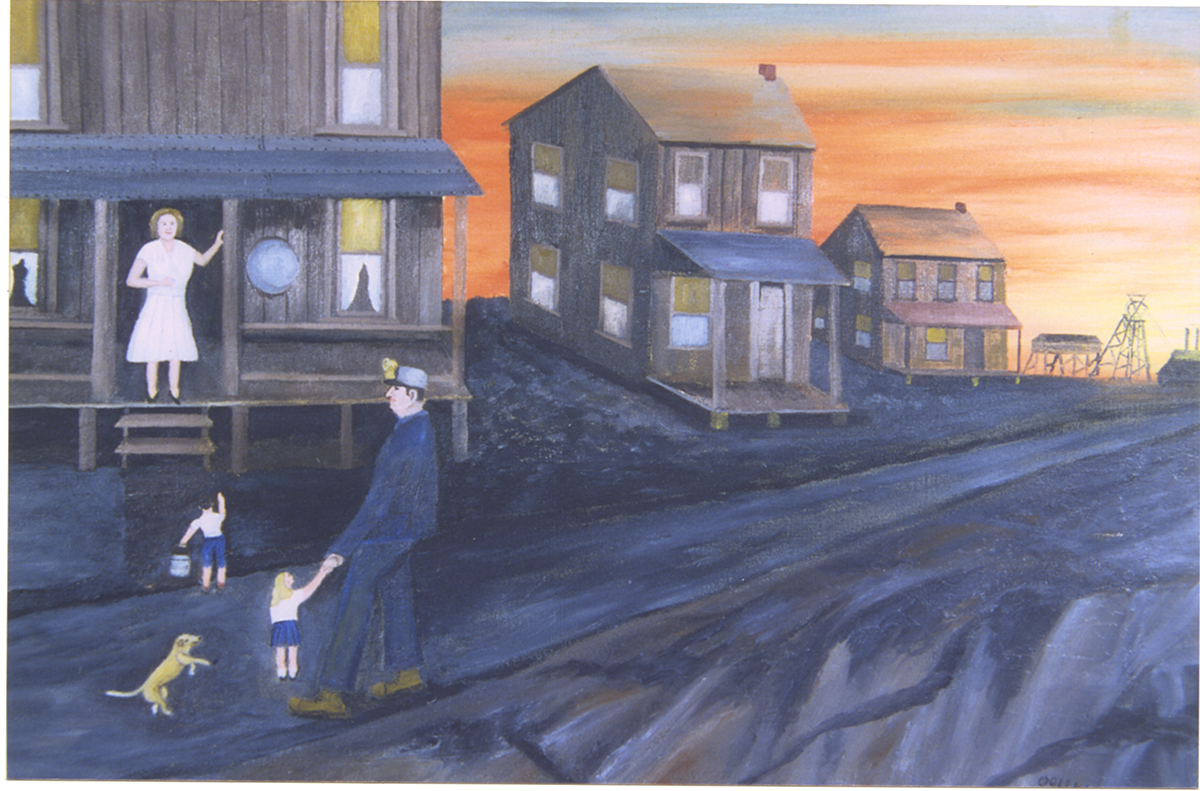

In the back of the gallery on the fourth floor hangs a painting by John Michael O’Cilka titled “Coal Police.” This simple name belies the complex stage of Western Pennsylvania history that the painting represents. The scene pictures three mounted coal and iron policemen confronting a group of civilians, one of whom carries an American flag. A tipple and other mining structures stand in the background. A number of questions come to mind. Why are the policemen blocking the road? What are they discussing? What significance does the flag hold? A study of the artist and “coal company towns” – a town that a coal company built and owned – may illuminate the answers.

A native of Cambria County, Pa., O’Cilka worked in the coal industry as a mine inspector between 1939 and 1961. “Coal Police” is just one of 30 of the self-taught artist’s paintings in the History Center’s collection. Many depict his personal memories of life in a coal town as well as scenes from earlier time periods. Not confining his paintings to firsthand experiences, O’Cilka often portrayed mining practices that were outdated by his day. For example, although “Coal Police” is dated c. 1960, it likely describes a scene from the 1920s because the coal and iron police became obsolete by 1931.

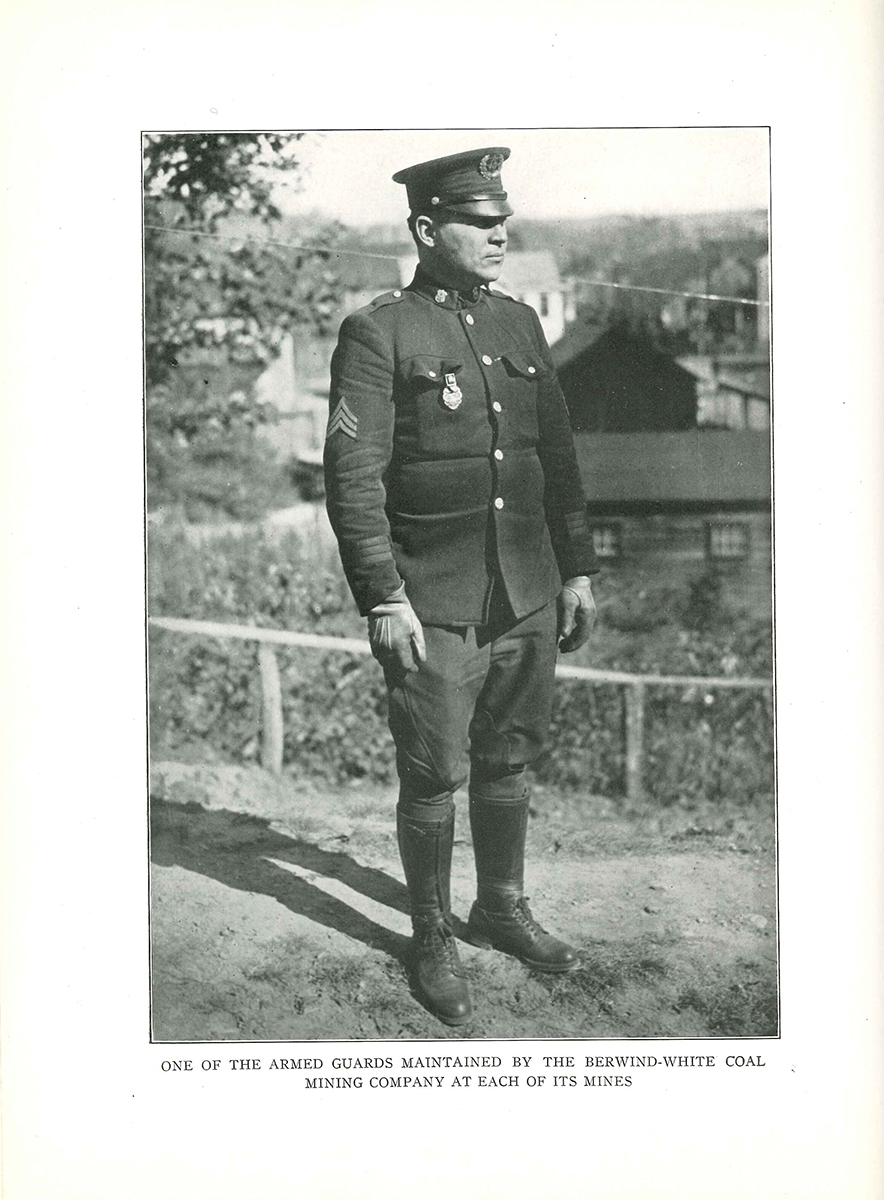

O’Cilka’s depiction of police denying entry to a mine suggests that he was portraying a coal company town. Imagine, for a moment, that you live in a town owned completely by your employer. The house you sleep in, the store you shop at, and the police who patrol the streets are all owned and controlled by your boss. Although this sounds strange, less than a century ago, mining communities were all over Southwestern Pennsylvania. Despite being geographically within America, where civil liberties were protected, corporate hegemony made the company towns virtual islands outside U.S. governance.

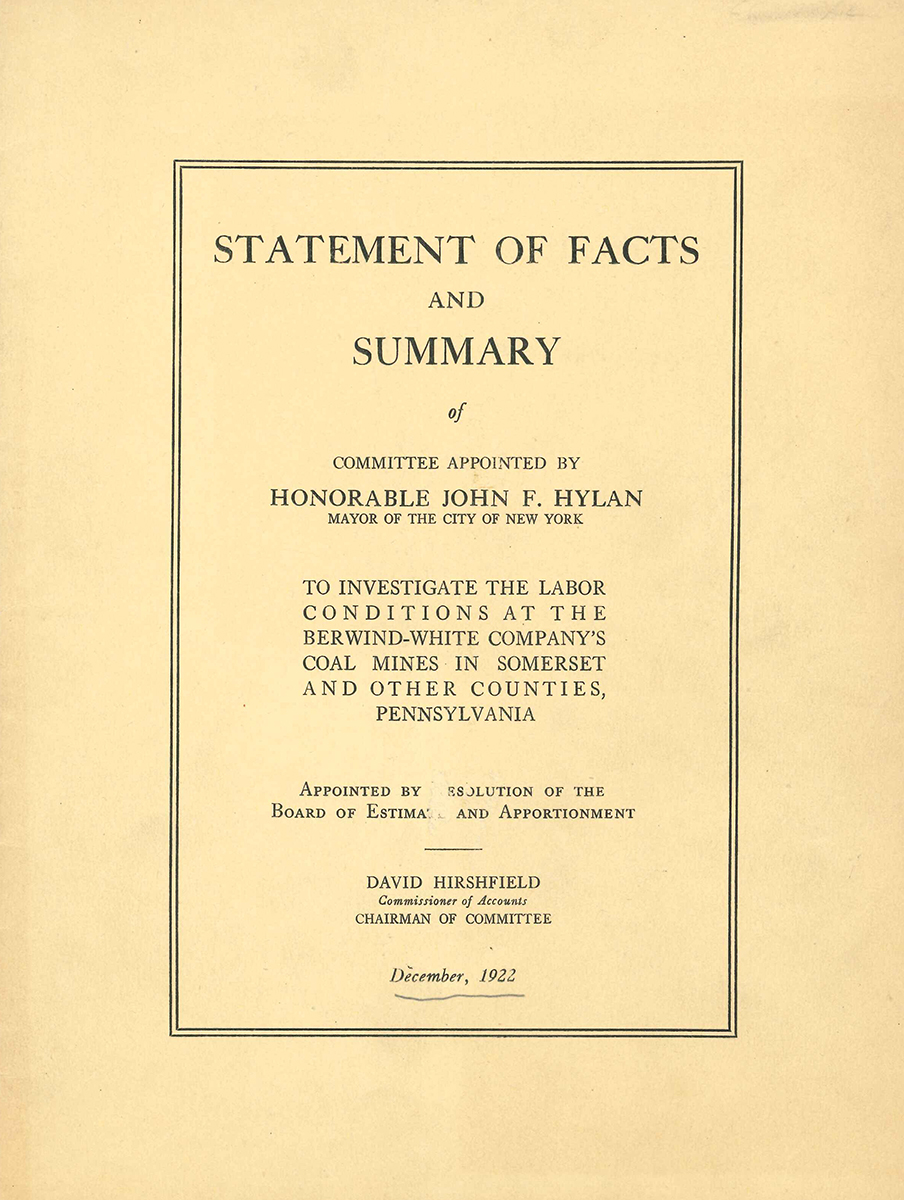

Recently, I paid a visit to a former company town in Cambria County, Pa., and talked with a resident who recalled the enforced curfew and the nightly warning whistle that sent children running home to avoid being caught by the company police. O’Cilka was likely familiar with the methods used in company towns since he worked for Berwind-White Co., which owned numerous towns. The conditions its inhabitants endured during the 1922 coal strike are detailed in a report in the History Center’s archives.

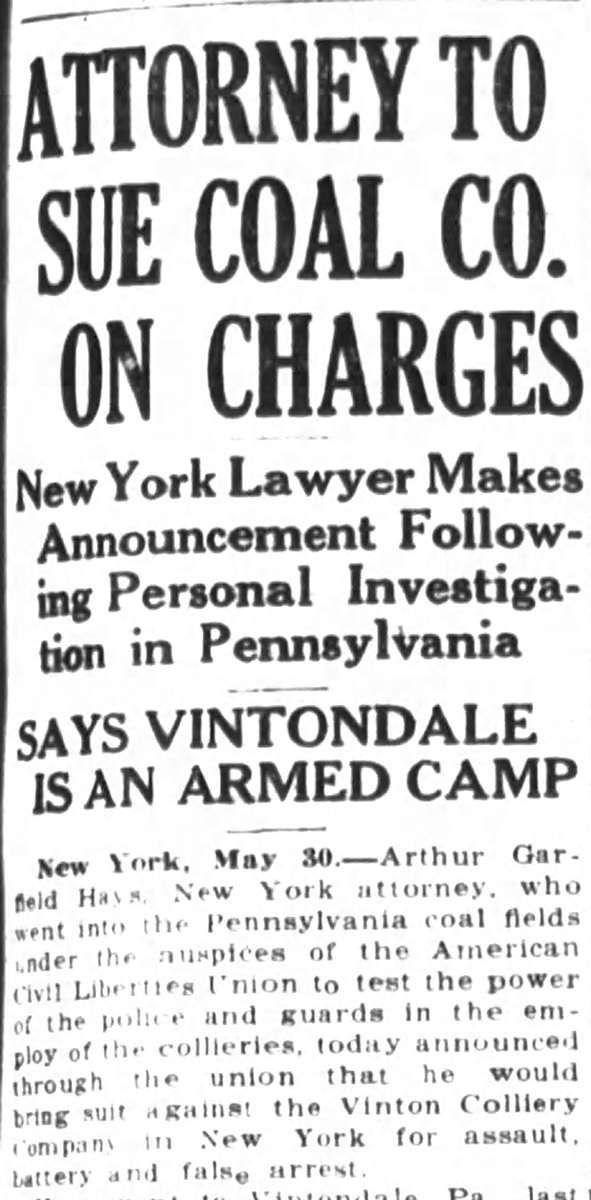

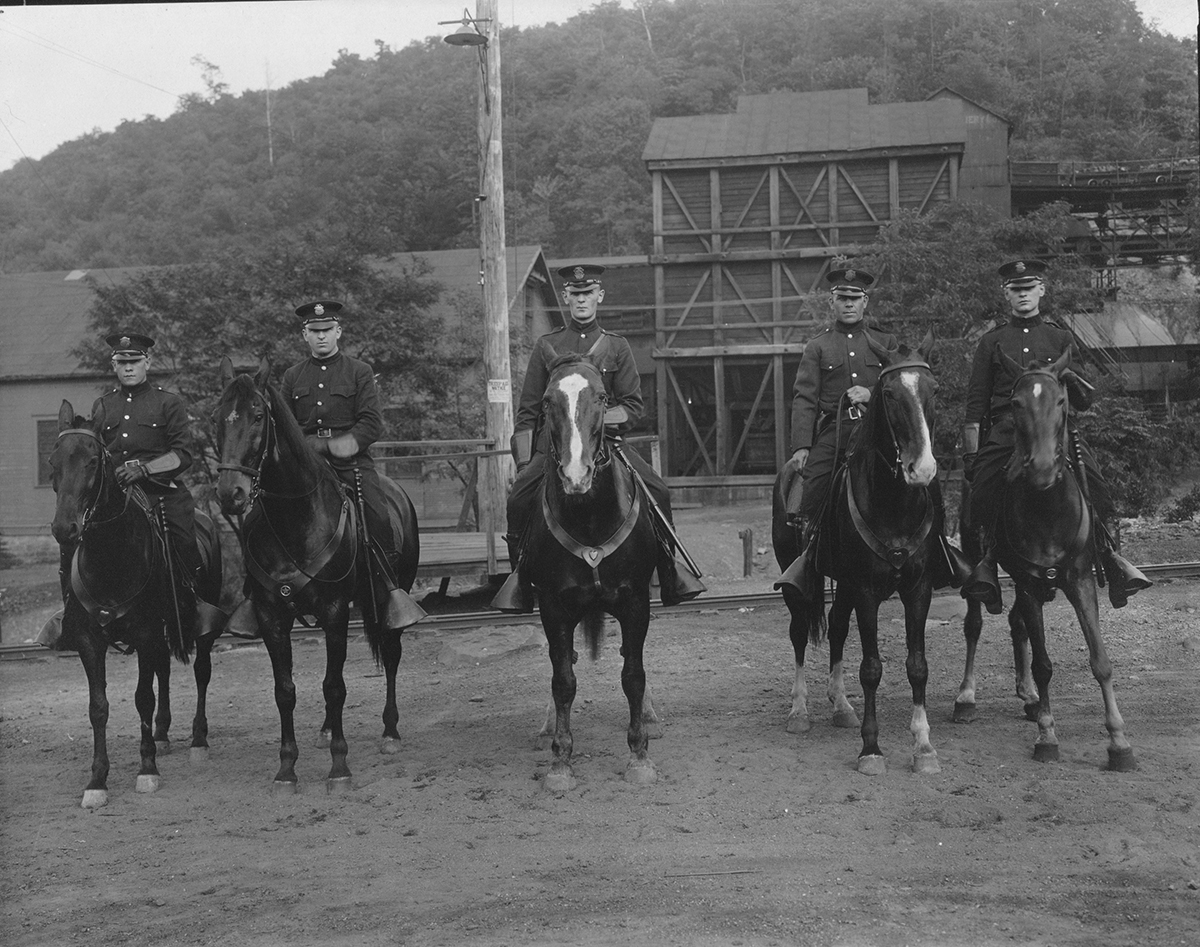

When he painted “Coal Police,” O’Cilka was probably thinking of an incident that occurred not far from his hometown. Sixty miles east of Pittsburgh lies a borough named Vintondale, a name that gained national attention during the 1922 coal strike when its coal and iron police arrested lawyer Arthur Garfield Hays. His crime was merely entering the town. When thousands of miners went on strike after a wage cut, most mines in the region shut down. Vintondale was an exception. Its employer, the Vinton Colliery Company (VCC), held strict control over everything from housing to legislature and had the courts issue injunctions, including a ban on assembling in groups of three or more and free speech through control of the press. Spies were employed to report on union activity, and the accused were evicted, which meant company police went into the miner’s house, removed all belongings, and dumped them outside. The company was also vigilant against outsiders, stationing guards on the roads to stop visitors and bar entry to those who might be union organizers.

Word spread that unionizing attempts in Vintondale resulted in arrests and evictions, and the ACLU asked Hays to test the legality of the coal companies and their police in preventing meetings. Hays found Vintondale an “armed camp.” He was physically forced to leave by mounted police brandishing clubs. When he returned with arrest warrants, he was arrested for trespassing. Newspapers reported how Hays brought suit against the coal and iron police for assault, and the VCC for violating free speech and assembly. Although the policemen were found guilty, Hays lost the suit against the VCC, which testifies to the level of corporate power that could be achieved in a company town.

This story of outsiders trying to bring American ideals of liberty inside a guarded company town may have inspired O’Cilka to paint “Coal Police.” Did he intend the flag to symbolize the miners’ struggle to claim their constitutional rights and their defiance against corporate power? What does the painting mean to you?

Further Reading

- Beik, Mildred Allen. “Remembering the Strike for Union in 1922-23, in Windber and Somerset County, Pa. 75 Years Later,” 1997. Available from the Detre Library & Archives.

- Weber, Denise Dusza. “Delano’s Domain: A History of Warren Delano’s Mining Towns of Vintondale, Wehrum and Claghorn.” Indiana, Pennsylvania: A. G. Halldin Pub., 1991. Available from the Detre Library & Archives.

Amanda Seim is an intern volunteer with the museum division at the Heinz History Center.