A version of this article appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of Western Pennsylvania History magazine.

October 25 is World Pasta Day

For many people, Italian American culture is synonymous with Italian food. And who could fault individuals for thinking this way, considering the pervasiveness of Italian American cuisine in the United States today. The widespread popularity of Italian food was not always the case; during the New Immigration Period (1890-1924) when waves of Italian immigrants were pouring into the U.S., French-influenced cuisine was the standard fare found in American hotels and restaurants.[1] In this era, Italian ingredients were relegated to the cucina, or kitchen, of the Italian immigrant. The evolution of pasta-making in American homes can be traced in the History Center’s Italian American Collection through an investigation of several of our artifacts: the chitarra, the hand-crank pasta machine, and the pasta die.

Before pasta was available for purchase in the grocery store, this staple of the Italian diet was made almost exclusively in the home. Italian families rolled pasta fresca by hand in a variety of shapes as diverse as the regions of Italy. Some employed the use of a chitarra (pronounced key-TAHR-rah) to produce spaghetti alla chitarra. This apparatus, whose name translates to “guitar” in English, was called so because of its wired construction. A rolling pin or similarly shaped tool would flatten dough into thin sheets that were placed onto the strings of the device. Another roll of the pin and the dough would be cut into long, rectangular noodles. Pasta produced by this method could be cooked immediately or hung on wooden rods to dry.

Gift of Marilyn Di Matteis.

The History Center has two chitarras in the Italian American Collection, each handmade locally. One, donated by Dorothy A. Petrilli in 1994 in honor of her late husband Herman A. Petrilli, was used by four generations of the Petrilli family. Originally owned by Mr. Petrilli’s great-grandmother, a resident of the Italian section of East Liberty, it was made around the turn of the 20th century by an Italian resident of Bloomfield. The other, donated by Marilyn Di Matteis in 2010, was made by the donor’s maternal grandfather in the 1930s with scraps from the steel mill where he worked in Weirton, W.Va.

Businesses catering to Italian American appetites, from grocery stores to bakeries to kitchenware manufacturers, were established throughout the region as the Italian American population steadily grew. Acknowledging that there was a faster way to make pasta, the hand-crank pasta machine was patented in Cleveland by Italian immigrant Angelo Vitantonio in 1906.[2] The kitchen tool quickly spread across the Italian American community as it allowed for faster production as well as the ability to create more than one style of noodle.

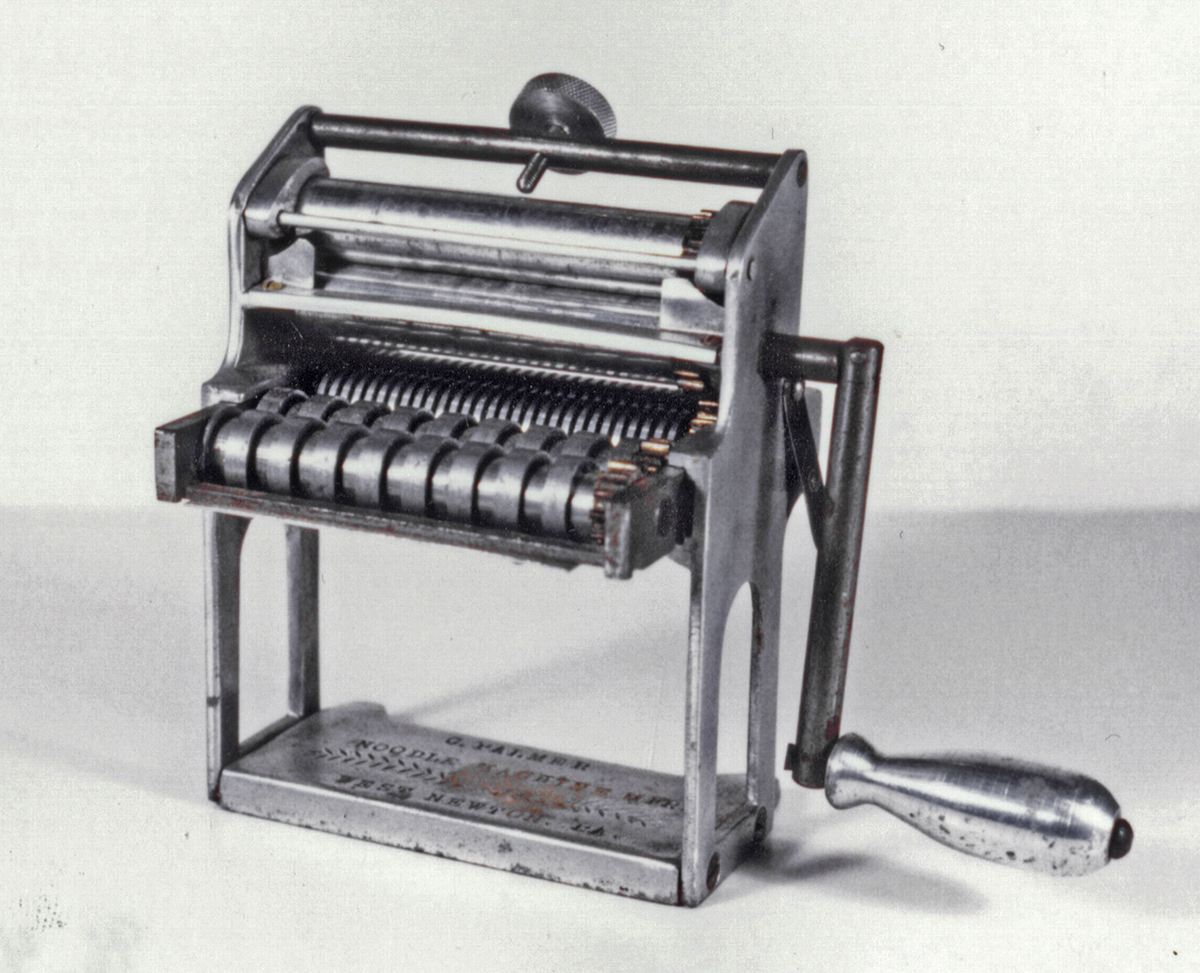

The acclaim of Vitantonio’s pasta machine led other individuals and companies to develop and mass-produce similar machinery. In our collection, we have a metal pasta machine from C. Palmer Manufacturing Company donated by chef Rizzi DeFabo of Rizzo’s Malabar Inn. DeFabo’s grandmother, Rosina DeFlorio of Greensburg, bought this hand-crank pasta machine in the 1950s. It has four cylinders of different size molds for pasta strips and a separate cylindrical compartment for rolling larger strips. Carmen Palmieri, an Italian immigrant from Lettopalena, Italy, established C. Palmer Manufacturing in 1946 in West Newton, Pa. He began the company designing pizzelle irons in his basement, then expanded to offer die cast molds and, eventually, electric appliances.[3] The company still operates in Westmoreland County.

By WWI, American attitudes towards Italian flavors improved as Italy was an ally of the U.S. During the 1920s, Italian Americans were celebrated in print media for their thriftiness, particularly when it came to their ability to cook meals without meat, and Italian-inspired dishes became more common in non-Italian American households.[4] With more people desiring Italian ingredients and a growing market for dried pasta, many macaroni factories materialized around the country.

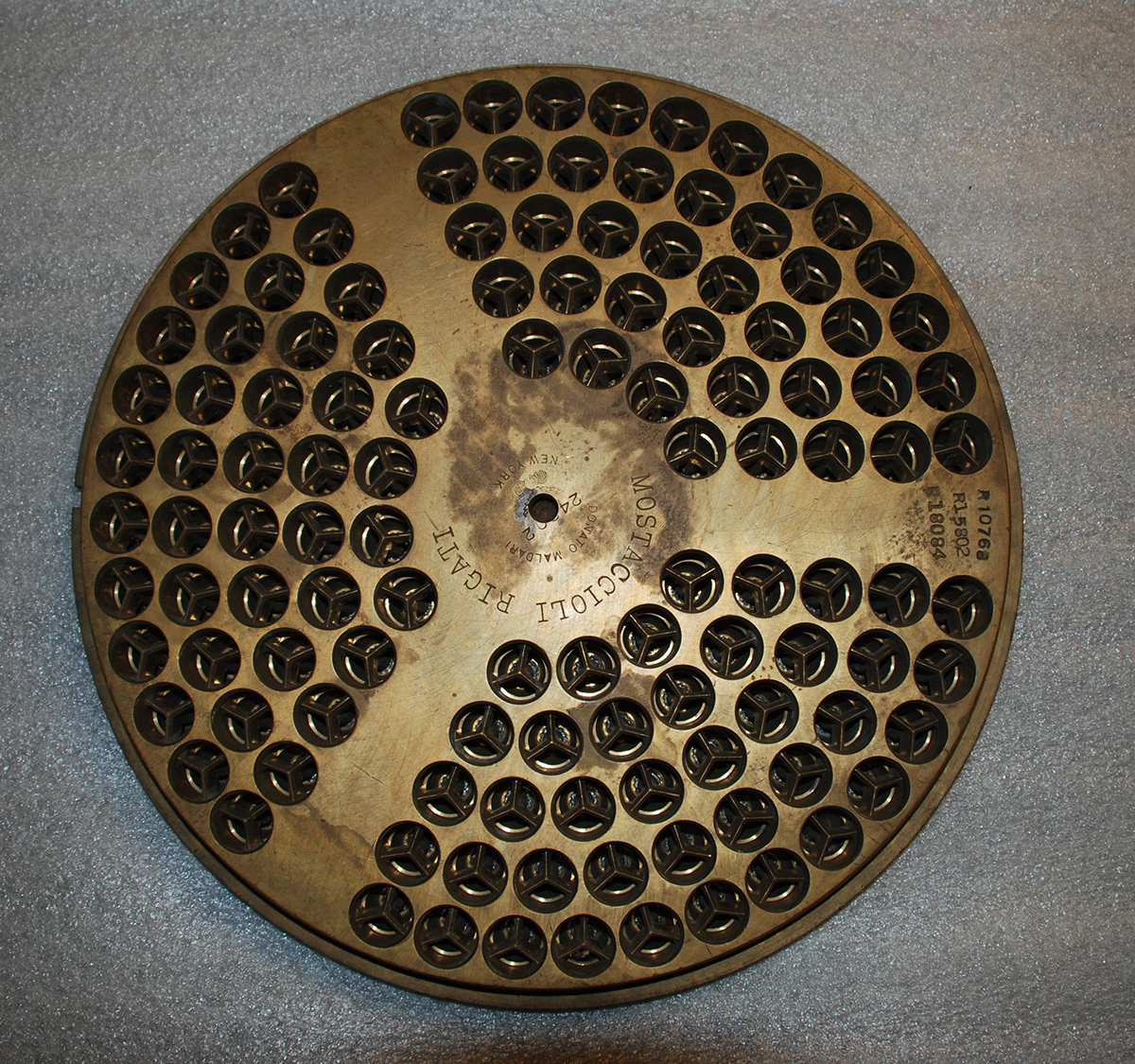

The Viviano Macaroni Company was one of the nation’s largest macaroni factories; it manufactured approximately 100,000 pounds of noodles per day, earning its owner Salvatore Viviano, an immigrant from Sicily, the nickname “Spaghetti King.”[5] Viviano and his heirs operated the company, known as Vimco Pasta, in suburban Collier Township from 1917 to 1985. The Italian American Collection has a large brass pasta die from Viviano’s factory. Pasta made in factories was produced by the extrusion method, where dough is forced through a shaped die, cut at the desired length, and heated to remove excess moisture.

The pasta-making pieces in the Italian American Collection that once may have looked alien to American cooks are now common appliances sold in stores. Likewise, pasta has become a staple of the American diet and Italian-influenced cuisine is among the most popular in homes and restaurants. You don’t have to be a foodie to try your hand at making pasta fresca at home—all you need is flour, eggs, a little bit of elbow grease, and an appetite.

[1] Harvey Levenstein, “The American Response to Italian Food 1880-1930,” Food and Foodways: Explorations in the History and Culture of Human Nourishment 1 (1985): 3.

[2] Vitantonio was not the first to invent the hand-crank pasta machine, only the first in the United States to patent and mass produce the device.

[3] Johnna A. Pro, “Immigrant’s success was struck when pizzelle iron was hot,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 4, 2003.

[4] Sherrie A. Innes, Dinner Roles: American Women and Culinary Culture (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001), 97-98.

[5] Ruth Ayers, “Macaroni Mansion,” The Pittsburgh Press, September 26, 1934.

Melissa E. Marinaro is the director of the Italian American Program at the History Center.