Sometimes an object becomes so associated with a certain era that it eventually symbolizes larger issues that shaped part of American history. For the 1920s, one such object was the Thompson Submachine gun, or “Tommy” gun. Nearly 90 years ago, the Tommy gun’s role as part of an event known as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre forever entwined the gun with the dark folklore of gangsters and Prohibition-era crime.

A Thompson submachine gun from the collection of the Senator John Heinz History Center currently appears on display in the new exhibition American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. Here, it reminds us of the great challenge faced by police departments across the nation during the 1920s. Purchased by the city of Pittsburgh in 1929, the gun symbolizes a local turning point in the effort to counter gang-related violence fueled by Prohibition.

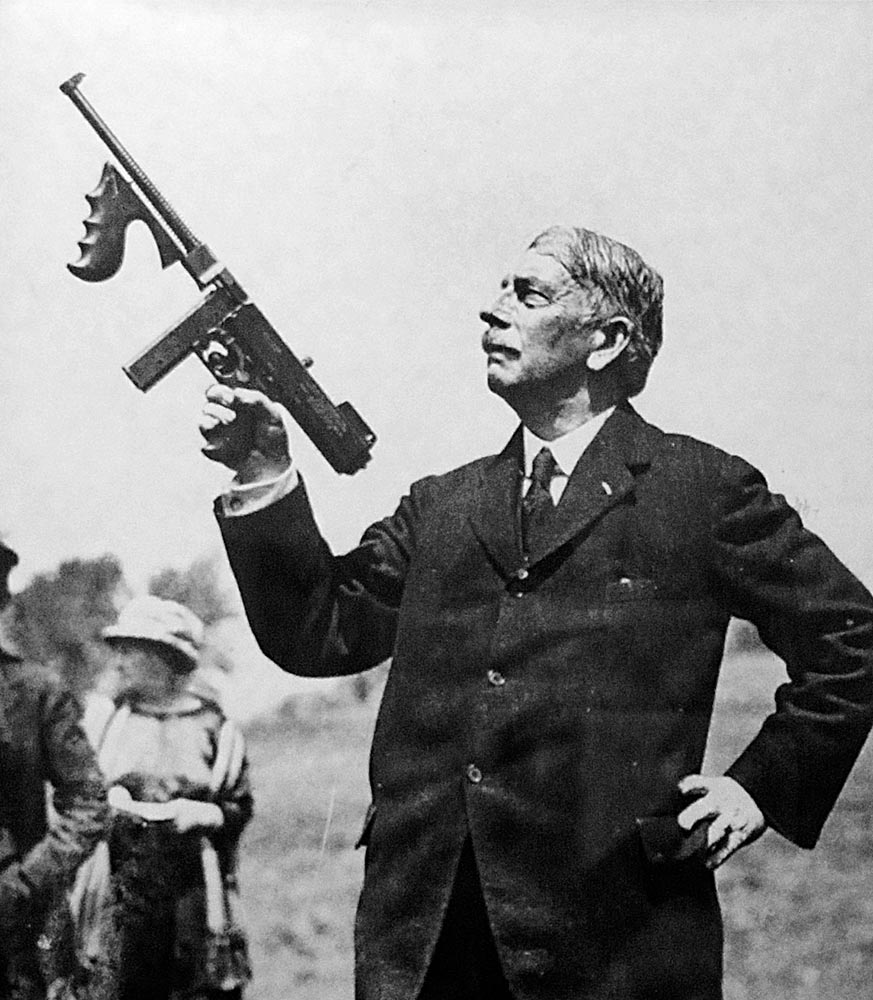

Originally, the Tommy gun was designed to help win a different kind of war. It emerged as a response to the disaster of trench warfare during World War I. Its creator, General John T. Thompson, spent much of his professional career with the U. S. Army Ordnance Department. During the height of World War I, Thompson envisioned a tool that would mitigate the horrors of trench warfare by clearing those trenches with firepower rather than manpower—a “trench broom.” The early name for Thompson’s gun was the “Annihilator.” But by the time a commercially viable version was ready, World War I was over. When the gun finally hit the market in 1921, early orders were slower than its creator had imagined. The gun was expensive: one cost $200, the equivalent of more than $2,700 today.

Few local law enforcement agencies could afford such a weapon, or perhaps they were not convinced they needed it. Violence did not erupt in the aftermath to Prohibition overnight. But by the mid-1920s, bootleggers and gang members had both the cash and the motivation to acquire such a weapon at just the moment when Prohibition’s booze-fueled financial windfall lit the fuse that transformed small local gangs into larger, more violent criminal organizations. For some criminals, the Thompson submachine gun, originally available through general retailers such as hardware stores, arrived at just the right time.

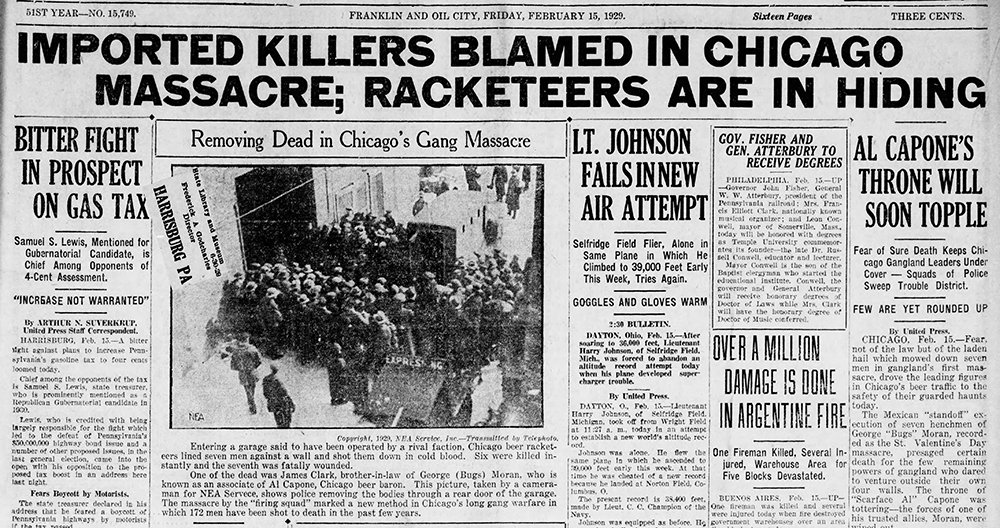

In truth, the number of criminals who bought Tommy guns was probably far smaller than the popular image suggests. But as violent gang activity increased in major American cities, especially Chicago, the presence of the Tommy gun as a criminal’s weapon of choice attracted great notoriety. General Thompson’s trench broom became known as a “Chicago typewriter.” It garnered special infamy on Feb. 14, 1929, when Tommy guns were used in the execution-style murder of seven men connected to George “Bugs” Moran’s gang in a North Side Chicago garage. This mass-execution made headlines nationwide as the “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.”

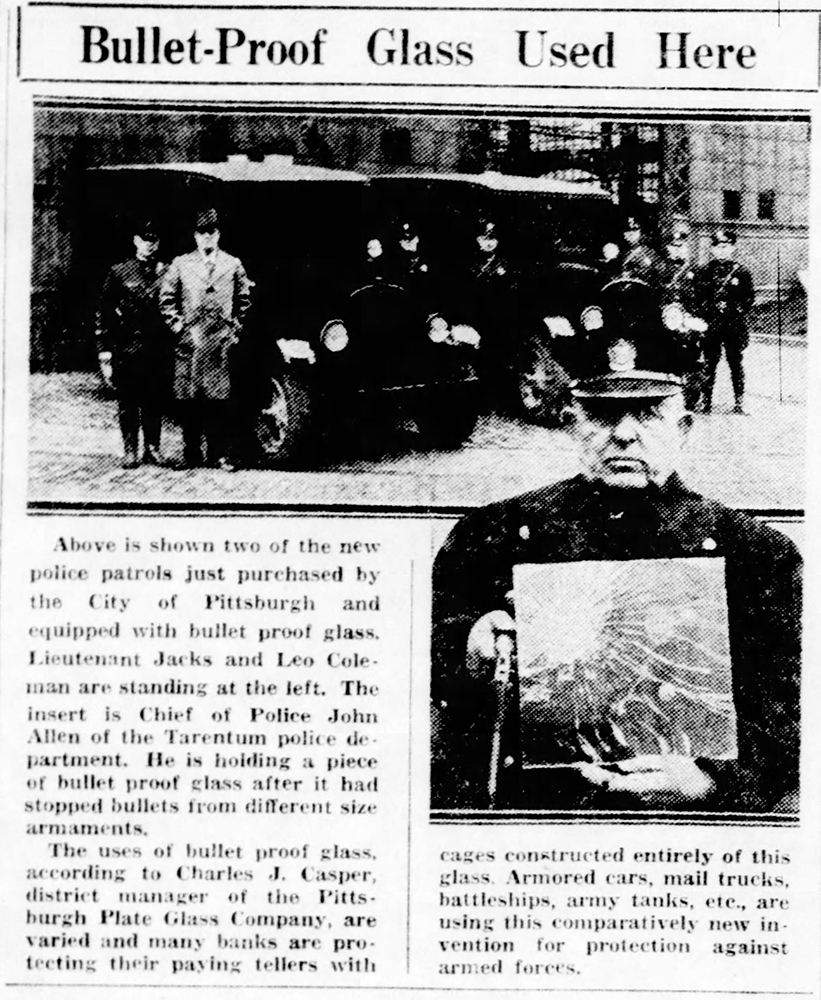

The event marked a turning point for public views about gang-related crime. City police departments such as Pittsburgh’s began to take another look at higher-powered weapons and crime prevention tools. In March 1929, Pittsburgh police officers received new patrols cars equipped with bullet-proof glass.[1] By June, the city’s detective bureau had secured permission to purchase a “high-powered, partly-armored” automobile that was supposed to include compartments for riot guns, tear gas bombs, and other crime suppression tools.[2] In July, Pittsburgh officials may have seen the demonstration of the Thompson submachine gun that was offered at the Pennsylvania Police Chiefs annual convention in Bethlehem, Pa. [3]

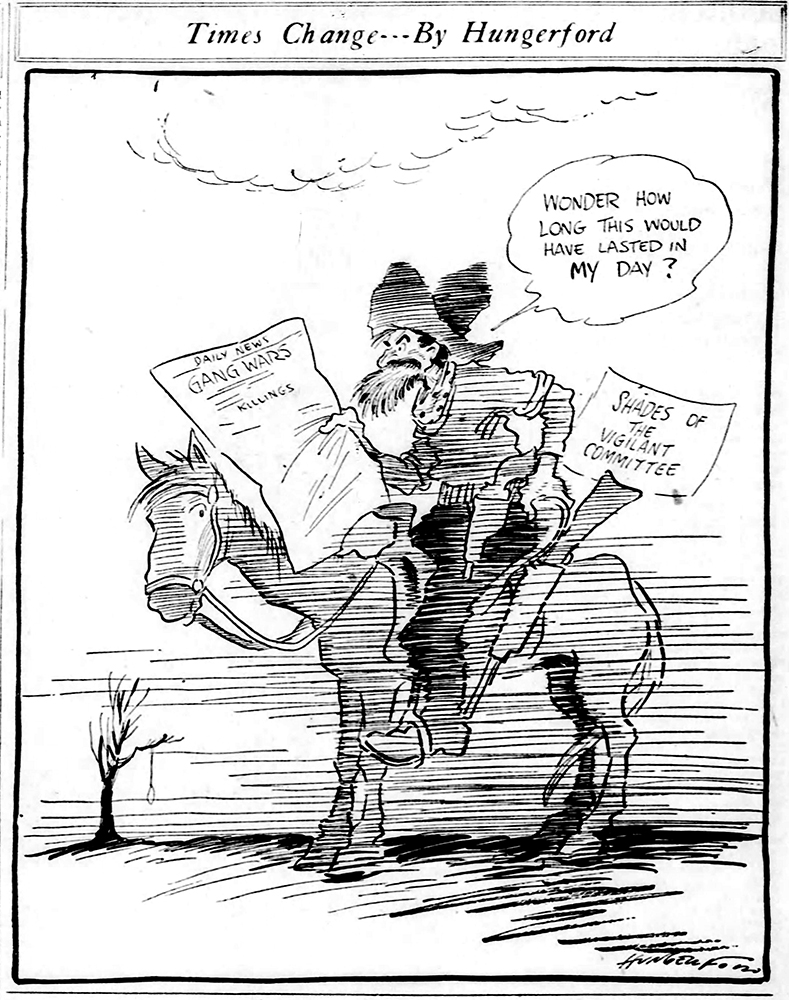

In Pittsburgh, the final straw probably came in August 1929. On the very first day of the month, a downtown Penn Avenue warehouse connected with suspected bootleg distiller and supplier Morris Curran was bombed. On Aug. 6, Pittsburgh’s “Racket King” and bootleg supplier Steven Monastero was shot to death by a “squad of killers” in front of St. John’s Hospital on the Northside.[4] Now everyone took notice. Three days later, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette cartoonist Cy Hungerford penned his own commentary with a pointed cartoon evoking the ominous specter of vigilante justice. (See cartoon at right.) A day later, someone asked in a letter published in the Pittsburgh Press, “Why are armored automobiles filled with men carrying loaded guns, permitted to roam the streets unmolested by the police?”[5] Clearly, public sentiment was wearing thin.

Whatever the final motivating factor, the approval to purchase two Thompson submachine guns was secured sometime that fall. By early November 1929, the guns were on their way to Pittsburgh. Receiving these weapons did not solve the city’s ongoing war with gang crime, which reached its bloody crescendo three years later with the dramatic hit on the Volpe brothers in July 1932. But the guns represented a key moment in the battle, when the city gave its own police force the same firepower being employed by the men they were trying to fight.

[1] “Bullet-Proof Glass Used Here,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 20, 1929.

[2] “Police to Get Armored Car,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 5, 1929.

[3] “Police Chiefs to Ask Legislature to Pass Law Defining Drunkenness,” The Morning Call (Allentown, Pa.), July 25, 1929.

[4] “Racket King is Slain in Northside Ambush,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 7, 1929.

[5] “Demand Mayoralty Candidates Pledge Opposition to Power of Armed Gangsters,” The Pittsburgh Press, August 10, 1929.

American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition brings the story of Prohibition vividly to life, from the dawn of the temperance movement, through the Roaring ’20s, to the unprecedented repeal of a constitutional amendment.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.