Pittsburgh born and trained artist Burton Morris makes the ordinary extraordinary, animating everyday objects to create symbolic statements about popular culture and our times. For almost three decades, Morris has invited us to see the world in a new way – painting with a bold, bright palette that belies the grey often associated with Pittsburgh.

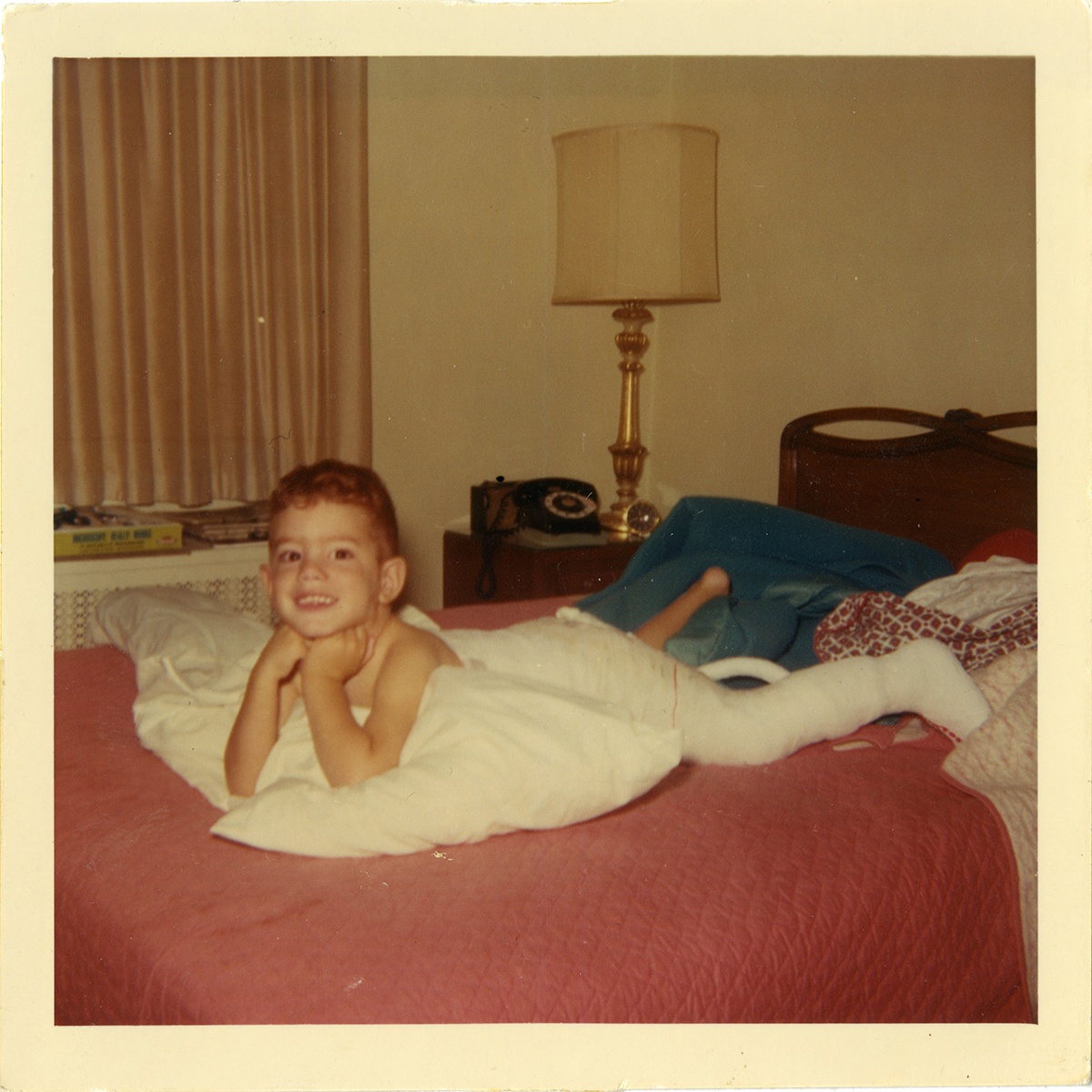

His interest in art started with an injury that left him in a sort of quarantine. Morris, then 3 years old, tried to emulate his television hero, swinging like Tarzan on the monkey bars. A bad fall landed him at the hospital; a broken femur resulted in a body cast. Unable to move by himself, Burton spent weeks laying on his parents’ bed, watching cartoons and drawing. His first efforts were simple crayon drawings of cars and airplanes. But as he drew, a love of creating something new, of putting ideas on paper, grew.

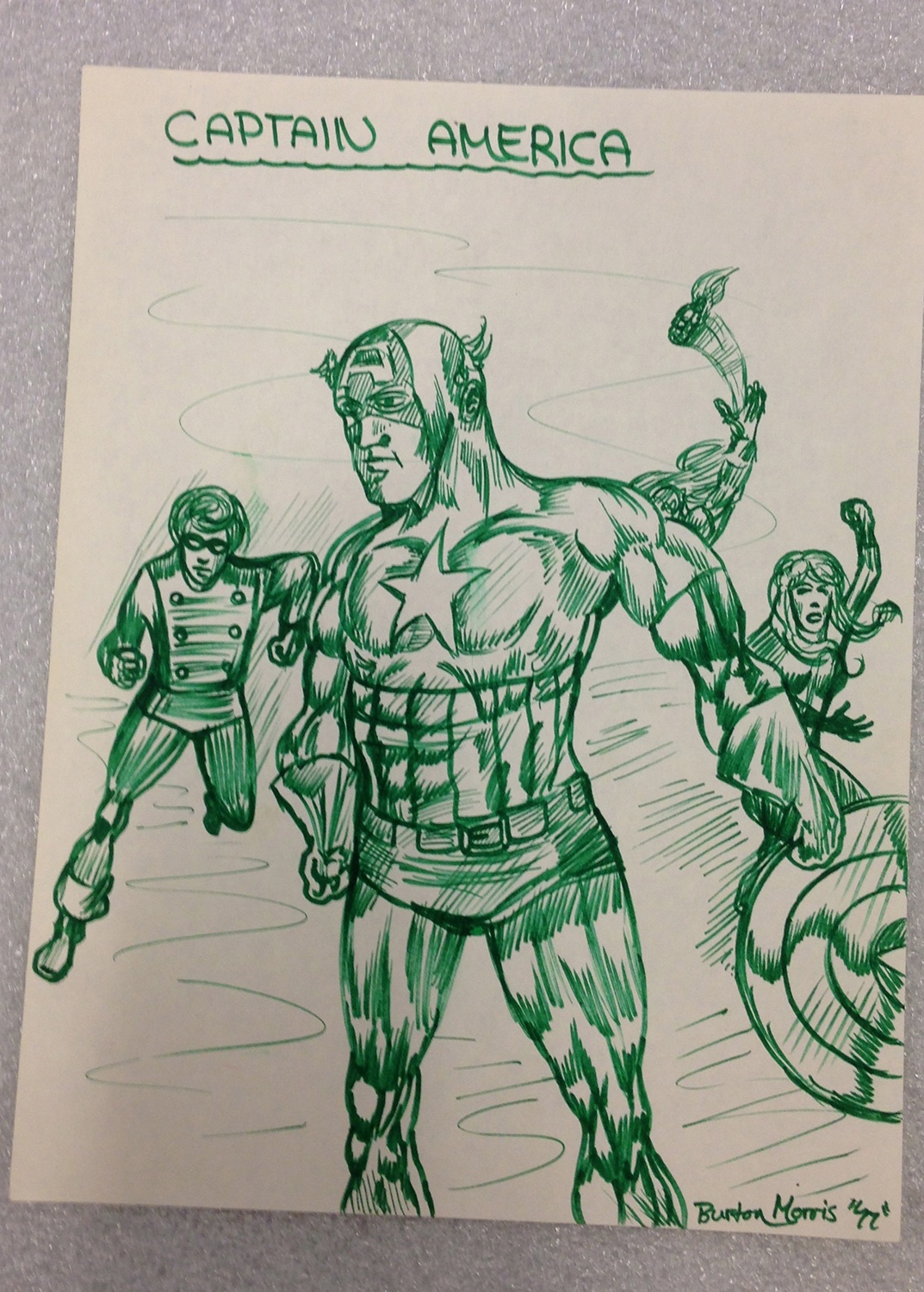

As Burton got older, his fascination with comic books inspired him and increasingly he focused on drawing active, muscular superheroes. His schoolbook reports became brief summaries of a comic followed by pages of illustrations, and even his diary from age 12 contains “footnote” drawings of comic-like characters. The work led Morris towards tight detailed drawing. The gift of a rapidograph pen further encouraged him to create intricate pen and ink drawings.

Morris’ parents supported his talent – enrolling him in art classes at the Carnegie Museum and collecting and saving his work. Study at the College of Fine Arts at Carnegie Mellon University polished Morris’ skills in design and illustration. Hired by an agency, Morris worked as an art director after graduation, producing commercials and advertisements. He had his first published illustration in Pittsburgh Magazine in 1988. A desire to return to drawing led him to leave the agency and set up his own business, Burton Morris Illustration. Commercial work from this period details the key elements associated with Morris’ paintings – a spare portrayal of individual objects or ideas, presented in an active, energetic way.

Morris’ big break came in 1993 when Absolut Vodka ran a national campaign highlighting an artist from every state. Selected from more than 800 artists to represent his home state of Pennsylvania, the Absolut campaign gave Morris national exposure and linked him to a group of emerging artists.

That same year, Morris began to work with Fred Rogers, designing the art for the 25th anniversary of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” on PBS. Morris developed a special connection with Fred Rogers — the work of each inspired the other. Rogers became Morris’ mentor, demonstrating how to gracefully handle his fame and the importance of treating all people with kindness and dignity. He also encouraged Morris to use his art for the betterment of others, especially children.

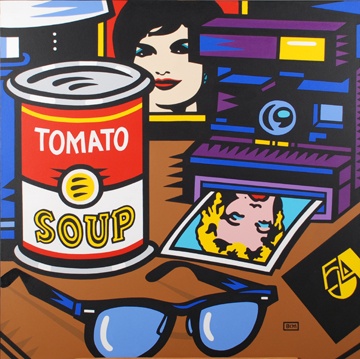

Morris quickly followed the Absolut campaign with another major achievement, placing his art on the popular television show “Friends” and building a network of connections in California. By this time, Morris had begun to create the icons that define his post-Pop style. All featured single objects rendered larger-than-life and symbolized new ways for Morris to present the everyday experience. At the same time, he continued his design work for corporate clients and began to broaden the market for his work beyond the United States. In 1996, Perrier hired Morris and two years later, he was hired as the official artist for the World Cup soccer games in Paris. The 76th Annual Academy Awards also asked him to redefine the look of the Oscars. In addition, Morris’ art branded charitable and fundraising events, raising millions for worthy causes.

Morris’ work also features nightstand portraits where the icon is a celebrity or famous individual represented by the personal objects that might sit on their bedside table. These nightstands are the answer to all the people who ever asked Morris if he painted portraits. In these intimate portrayals of famous people, Morris uses objects to unveil the story of their lives.

No matter where his art has taken him, Pittsburgh has remained a creative muse for Burton Morris. Though he makes his home on the West Coast, he returns often and organizations from the region still seek his talent to create art that brands their events or preserves special moments. Morris’ art has reimaged the city, casting a fresh vision of our region to the world.

Family and friends also draw Morris back to Pittsburgh. His roots here run deep and have played a role in the spirit and tone of the art he creates. Though Morris now signs his work, many of his early paintings bear a mark, “BCM,” which stands for Burton Charles Morris. His name pays homage, in the tradition of the Jewish faith, to his great-grandmothers. His first name begins with a “B” to recall Bertha Weinberg, his middle name a “C” for Clara Spiegle. Both were gone before Burton came along, but their spirits lived on in their children. One of those children, Burton’s “Nanny Annie,” made her way from Ukraine to Pittsburgh in 1914 at age 15. She quickly involved herself in her immigrant Jewish community, joining with friends to found the Young People’s Zionist League. Her daughter, Burton’s mother, is a retired high school health teacher and community activist. These strong women imbued Burton with their energy and their positive outlook. That hopeful nature is preserved in the art Morris creates.

Anne Madarasz is the Director of the Curatorial Division, Chief Historian, and Director of the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum at the Heinz History Center.