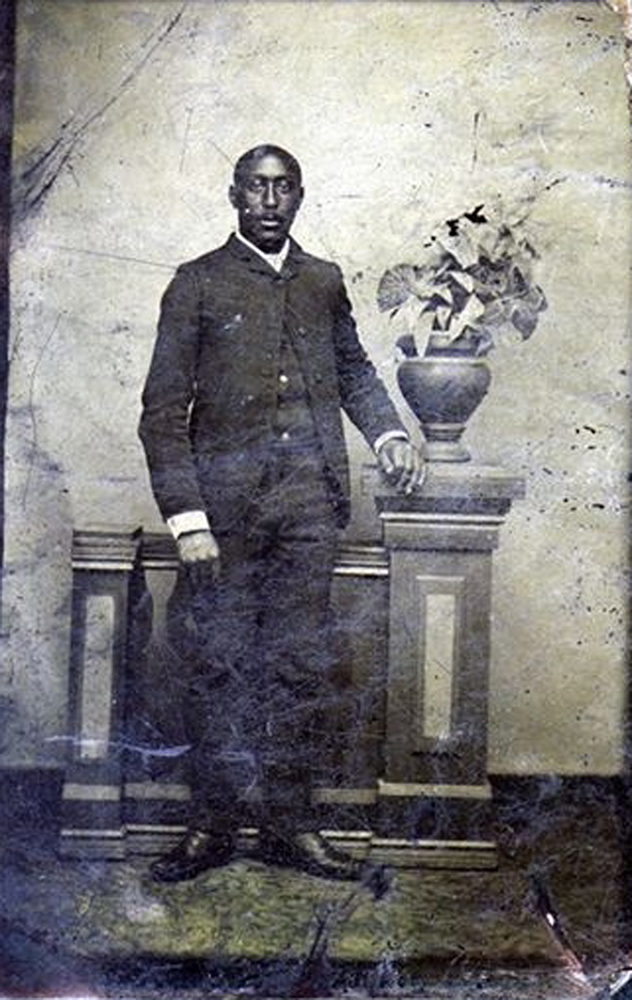

At the height of the movement to rid the nation of slavery – the abolitionist movement – Martin R. Delany was one of the more charismatic and practical leaders of the time.

Delany was born free to a free mother, Pati, in Charles Town, Va. in 1812. His father, Samuel, was enslaved. Pati was literate and taught her children to read. Delany and his family moved to Chambersburg, Pa. in the early 1820s and would later be joined by his father, who was finally able to purchase his own freedom in Virginia.

In 1831, Delany, seeking greater freedom and the opportunity for higher education, traveled for months from Chambersburg to Pittsburgh, where he settled as a boarder with the family of Lewis Woodson. It was Woodson who counseled and further educated Delany and included him on trips to Philadelphia for Anti-Slavery meetings. Under Woodson’s tutelage, Delany advanced into a researcher, writer, and activist. By 1839, Delany had travelled in the Mississippi Valley to observe, research, and explore American slavery. This venture produced a serial article about slavery in America that was published in the Anglo-African Magazine. His return to Pittsburgh witnessed his greater involvement in abolitionist organizations. He helped found the Moral Reform Society and the Philanthropic Society.

In 1843, with investments from local African Americans, Delany founded The Mystery newspaper. The Mystery became the first newspaper by an African American west of the Allegheny Mountains. As editor and publisher of The Mystery, Delany attracted a growing audience. One such person was Frederick Douglass, who visited Delany at his home in Pittsburgh in 1847. Douglass proposed that Delany and he work together to edit the North Star newspaper, Douglass’ venture. Delany joined Douglass, but the collaboration only lasted a few years. In 1850, Delany was on his way to Harvard Medical School.

Unfortunately, Delany and two other African American medical students were met with hostilities from some of their classmates who signed petitions to have them dismissed. In 1851, they were released from Harvard – with credential. Before he returned to Pittsburgh, Delany stopped in New York City to patent a tool he had invented. When he was rejected because of his race, he made up his mind that America was not the place for progressive Black people. He then began to formulate ideas for mass Black emigration to Central and South America. He encouraged David Peck, a friend and former Pittsburgher, to go to Nicaragua. Delany began plans to establish a formal organization for the emigration of Blacks.

By 1854, the National Emigration Convention was organized in Cleveland, Ohio, with Delany presiding. This group gained significant momentum and by 1856 commissioned Delany to put together a team to travel to Africa to establish settlement. Also in 1856, Delany moved his family to Chatham, Canada West (Ontario, Canada). Soon after, he travelled to Liberia and then Nigeria to negotiate land leases among the Abeokuta in Yoruba land of the modern day Omo State. Delany was successful in his negotiations only to be thwarted by British colonial agents and the coming U.S. Civil War.

In 1863, Delany returned to the U.S. from his home in Canada to recruit for the newly established United States Colored Troops to defend the Union against the Confederacy in the Civil War. One of his first recruits was his son, Toussaint. In February 1865, Delany met with President Lincoln at the White House to talk about the establishment of a permanent force of Black troops commanded by Blacks in the South to protect and guarantee the new freedom for the nearly four million ex-slaves. Lincoln commissioned Delany a Major in the 4th USCT in the Army of the South station in the Low Country of South Carolina. Within months, Lincoln was dead and the war was over. Delany, however, remained in South Carolina as a Federal employee of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

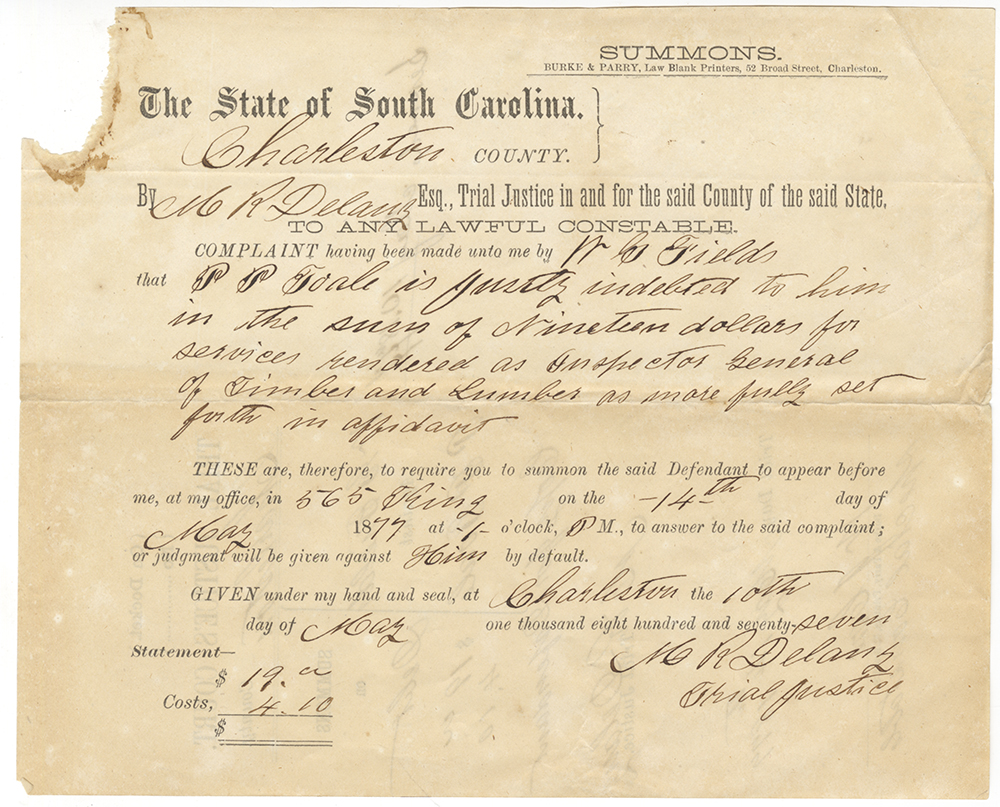

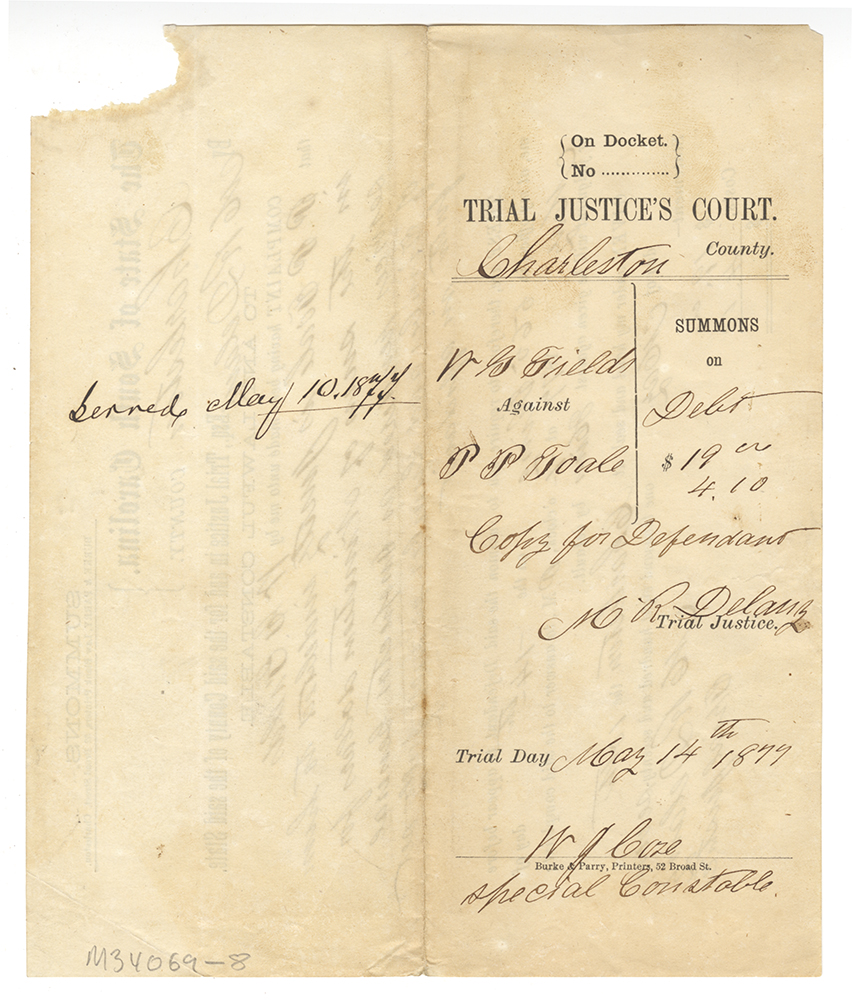

After his service to the government, he remained in South Carolina, where he was elected as a Trial Justice. This 1877 summons is evidence of Delany’s role as a trial justice in South Carolina. The signed summons is one of the few existing documents that is in Delany’s hand. Most of his personal papers were destroyed in a fire at Wilberforce University decades ago.

Samuel W Black is the director of the African American Program at the Heinz History Center.