In a report on Pittsburgh’s “smoke nuisance” in the early 20th century, academic researchers attempted to calculate the economic burden caused by the city’s air pollution. They found that Pittsburghers, in their ongoing battle against soot, spent more on replacing curtains, refreshing wallpaper, and repainting homes than residents of cleaner cities. To keep the grime off their clothes, they also made more trips to laundries and dry cleaners, making Pittsburgh, in the eyes of a writer in 1913, “the greatest laundry town in the country.”1

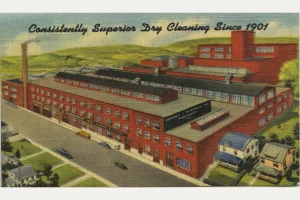

Living in this land of opportunity, Alfred E. Crandall and Orel McKenzie opened a dry-cleaning business in 1901. The Crandall-McKenzie Company started in a small building on Chaucer Street in Pittsburgh’s Homewood neighborhood. In time, the operation grew into a two-building plant occupying an acre of land. An illustration of the enterprise shows the sprawling complex situated in the middle of a residential neighborhood, occupying the better part of the block. After merging with another dry-cleaning operation, it became Crandall-McKenzie & Henderson and expanded to Pittsburgh’s North Side neighborhood. Far from being a modest neighborhood dry cleaning business, Crandall-McKenzie & Henderson employed more than 200 people and was publicly traded on the Pittsburgh Stock Exchange.

The Detre Library & Archives’ Crandall-McKenzie & Henderson Records include photographs, administrative records, and promotional material that shed light on the history of business. A pamphlet in the collection reveals that a custom cleaning method called the “Cleanthru” process was central to the firm’s marketing strategy. Though vague on the particulars, the company touted this process as a scientific procedure used exclusively by an experienced workforce to thoroughly clean clothing, rugs, and furniture. A series of photographs document the different aspects of this work, from the initial measuring of garments to a fleet of company vehicles (each emblazoned with “Cleanthru” on the side) waiting to deliver finished items back to customers.

The company also offered a dyeing service, providing customers with the option of transforming their light-colored garments into darker attire. According to Emily Crandall, granddaughter of the cofounder, not only was this useful for attending funerals, but darker clothes could also more effectively conceal dirt.2 This could be a more cost-effective strategy for customers rather than having clothes frequently cleaned. A researcher theorized that the city’s dry cleaners, as successful as they were, could be making even more profit had Pittsburghers not adopted this measure en masse. Residents so often wore dark clothing that it gave Pittsburgh the reputation of a city in a constant state of mourning.3

Complementing the archives are letters from John A. Crandall to his sister Emily that illuminate the role of dry-cleaning in the era before fast fashion transformed garment consumption. John recalled the heyday of the company as being from the 1910s through the end of World War II. He wrote that, during this era, “clothes were tailor and seamstress made and made to be altered as people changed.”4 Garments were passed down from one generation to the next, their durability enhanced by careful cleaning.

On a late summer evening in 1970, years after the Crandall family sold the business, an explosion rocked the Homewood plant. Nearby residents were evacuated as a six-alarm fire tore through the facility and caused damage to a neighboring house. Snapshots in the collection document the aftermath, depicting a pile of rubble on an empty plot, an ignoble end to a once-bustling site of business.

John Crandall considered the World War II years to be the apex of the business’s success when women working to support the war effort had little time to wash clothing at home. “Rosie the riveter had to send out her clothes during the war,” he remembered.5 After the war, clothes once made from natural fibers like wool, cotton, and silk were instead increasingly produced with synthetic fibers like nylon and polyester. Garments made from these materials required less care and were cheap to replace. Reformers were also making headway on Pittsburgh’s air pollution problem. The Crandall-McKenzie business carried on into the 1980s, but the firm’s peak had long since passed.