From 1910 to 1970, the Great Migration brought over six million African Americans to northern and western cities including Pittsburgh. New arrivals escaped Jim Crow laws, only to find opportunities still limited based on race in employment, housing, and accommodations. In navigating their new cities, a helpful tool for Black Americans was “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” published from 1936 to 1967 by Victor Green.

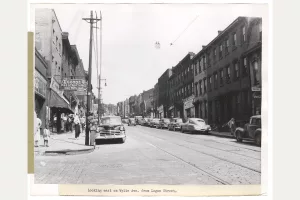

Marketed with the tagline, “Carry your green book with you. You never know when you may need it,” the Green Book guide was created to help African Americans travel the country with safety and dignity in the face of segregation and racism. The listings included in the Green Book highlighted Black businesses such as hotels, restaurants, drug stores, salons, and gas stations. Many of the businesses were in neighborhoods with a large African American population. In Pittsburgh’s Hill District, over 30 locations were listed in the Green Book.

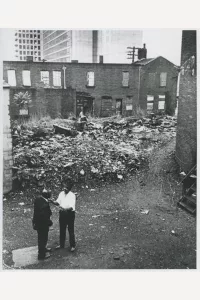

Today, many of those locations have been razed due to urban renewal. Urban renewal projects began to spring up in the late 1940s to 1960s and were implemented in partnership with government officials, developers, and corporate leaders. Under the guise of urban renewal, the government used eminent domain to seize and tear down properties marked as blight for redevelopment. The land targeted for renewal was often in neighborhoods that had significant African American, immigrant, or low-income populations. The people who lived in those areas were often excluded from the development process, while outsiders made plans for the communities they considered slums. Despite this, “The Negro Motorist Green Book” continued to expand its business listings in those locations. In Pittsburgh, such listings showcased the entrepreneurship of Samuel Scott whose service station was listed in 1940 and restaurant in 1946. On Wylie Avenue in the Hill District, travelers could visit Charlotte’s Beauty Salon.

During World War II, the Green Book was not in publication from 1942-45, given the rationing policies in place for food and gas. At home, redlining was taking place, restricting where African Americans could buy and rent houses due to housing covenants and laws passed during the New Deal. The Homeowners’ Loan Corporation drew maps designating redlined areas which were given a “D” grade and labeled hazardous. The Hill District was designated as such due to the “concentration of negro and undesirables, very congested.”

Easing some of these housing issues was the G.I. Bill which provided low-cost mortgages for returning veterans and funding for college. The initial G.I. Bill primarily excluded African American veterans as it was up to the states to decide how the funds were released. For African Americans who were able to receive the G.I. Bill, housing remained a barrier because of redlining. As for higher education, the Green Book wrote articles on how to use the G.I Bill and provided a list of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Following the G.I. Bill and the post-war boom in the economy, cities began to transform as more people moved to the suburbs – white flight in the urban areas led to major expansions of highways and the decay of many Pittsburgh buildings.

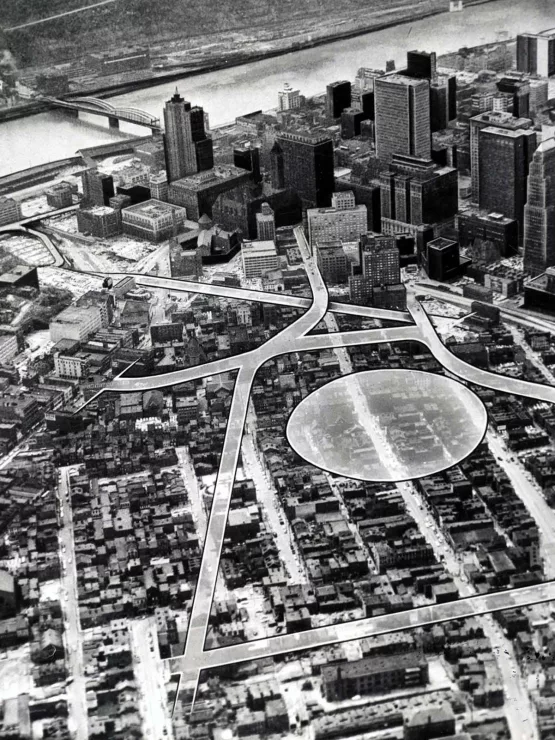

Led by Richard King Mellon, Pittsburgh began its post-war transformation with the Citizens’ Committee on Post-War Planning. Later known as the Allegheny Conference of Community Development (ACCD), the organization was officially founded in 1944 and included business and political leaders starting. The Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) was then created in 1946 to serve as the city’s redevelopment arm and helmed by Mayor David Lawrence. The city’s urban renewal initiatives that emerged from the creation of these two entities, the ACCD and URA, were referred to as the “Renaissance.” Pittsburgh’s first Renaissance projects aimed to clear the city of its smoky image with different air ordinances and to revamp downtown with new buildings and a park.

Following the creation of Point State Park and Gateway Center, City Councilman Abraham L. Wolk and department store owner Edgar Kaufmann looked ahead to the next Renaissance project – the creation of a civic auditorium for the Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera. The upper-class neighborhood of Highland Park was chosen for its location, but Robert King and fellow residents of the neighborhood spoke against the auditorium, receiving 1,000 signatures in opposition. In exchange for not using Highland Park, King offered his land to be turned into a park after his death. The planning for the auditorium shifted to the Lower Hill District.

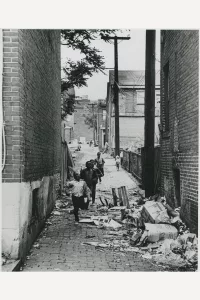

Upon deciding where to begin construction, City Councilmember George Evans described the Hill District as “one of the most outstanding examples in Pittsburgh of neighborhood deterioration … Approximately 90% of the buildings in the area are sub-standard and have long outlived their usefulness, and so there would be no social loss if they were all destroyed.”

Ultimately, Pittsburgh leaders took advantage of the 1949 American Housing Act – which provided federal funds to urban renewal projects that cleared out “slums” – and utilized both federal and private funds to plan the demolition of 95 acres in the Hill District for the new arena and cultural hub. But to many African Americans who lived there, the Hill District was far from a slum – it was home.

The Hill had a vibrant culture, earning the name the “Crossroads of the World” by Harlem Renaissance poet Claude McKay. Old timers and migrants created a community there that was a one stop shop for one’s needs. Within the neighborhood’s 95 acres sat many Green Book listings, the oldest African American church in the city, Bethel AME, and eateries like Ma Pitts and Nesbitt’s Pie Shop. Home to Pittsburgh’s groundbreaking jazz scene, the sounds of saxophones and piano riffs spilled into the streets. Locals could be found walking the Avenue recapping the latest Pittsburgh Crawfords game.

In 1955, the clearance of the Lower Hill District began. As the last bulldozer left the area, over 8,000 residents were displaced, as well as over 400 businesses.

In the proposal to gut the Lower Hill District for the forthcoming auditorium, the URA stated they would compensate the building owners for loss of property. But the people who lived in the buildings would not be compensated. Conversations began about rehousing Lower Hill residents elsewhere, but no solid plan was put forth for their relocation.

In the city’s new cultural district, the Civic Auditorium and one luxury apartment were built in the Lower Hill. The arena was billed as a marvel in modern architecture with a retractable roof. Yet the cost of repairs made it rare that the roof would open on a regular basis. Heinz Hall was constructed downtown. Today, parking lots stand at the intersection of Wylie Avenue and Fullerton Street where Homestead’s WHOD radio’s Mary Dee Dudley, aka “Mary Dee,” the first black female radio DJ, pinpointed as the crossroads of the world.

Following the initial demolition, there were plans to continue development in the Lower Hill with an eye toward the middle Hill. But the Citizens Committee for Hill District Renewal formed to take a stand against more urban renewal efforts. The committee and the NAACP took out a billboard on Roberts and Crawford Streets demanding low-income housing and no more development beyond this point. In the place of their once vibrant community were now parking spaces and unfinished plans for affordable housing.

The auditorium changed its name to the Civic Arena and eventually closed in 2010 to make way for a new arena. Today, the area marked for urban renewal consists of parking lots. Of the Green Book locations listed in the Lower Hill District, only one building remains. Conversations continue with community leaders and city officials on how to redevelop the “crossroads of the world” to this day.

Local leaders will delve deeper into urban renewal and how it reshaped the Hill District during a free panel discussion at the History Center on Tuesday, June 27. The conversation will be moderated by Miracle Jones, director of advocacy and policy at 1Hood Media, and is hosted in conjunction with the History Center’s new exhibition, The Negro Motorist Green Book.

References

Allegheny Conference on Community Development Collection, 1944-1993, AIS.1973.04, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System

Allegheny Conference on Community Development (Pittsburgh, Pa.), Photographs, 1892-1981, MSP 285, Library and Archives Division, Senator John Heinz History Center

Hill District Community Development Corporation Hill District Facts. Retrieved from here.

Urban Redevelopment About Us. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh.

Whittaker Mark. (2018). Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance. Simon & Schuster

About the Author

DaNia Childress, Associate Curator for African American History