Pittsburgh doesn’t seem to be an obvious place to be home to one of the most vocal Congressional boosters of American space research. But before the decline in the steel industry in the late 1970s and early ’80s, the city made its name as a blue-collar town built on the back of the steel, railroad, and financial industries. As the industrial heart of the United States, it became the third highest priority target in the event of a nuclear war after Washington and New York. As a hotspot for military-industrial innovation and a major producer of industrial metals such as steel and aluminum, the region contributed to the drive for space.

The region was home to Dormont’s long-time congressman James G. Fulton, an ardent advocate for space. Fulton used his position in Congress to bring the space race to Western Pennsylvania, spending the latter half of his 25-year career trying to generate high-tech jobs related to the space program.

Though little remembered today, Fulton argued for support for manned flight, urging Congress to fund the mission to be first to the Moon stating, “We are in a competitive race with Russia.” He feared that if the Russians conquered space, they would have a platform to wage nuclear war against the U.S. During a career that spanned from 1945 to 1971, Fulton was more of an internationalist than many of his fellow Republicans. He served in the Navy during World War II and his first assignment in Congress was to the Foreign Affairs committee, where he served from 1953 until his death in 1971. From his post, he took special interest in the nation’s work to rebuild Germany after World War II, and he helped oversee government investment in our South American allies. President Eisenhower tapped Fulton to serve as a representative of the United States in the General Assembly of the United Nations.

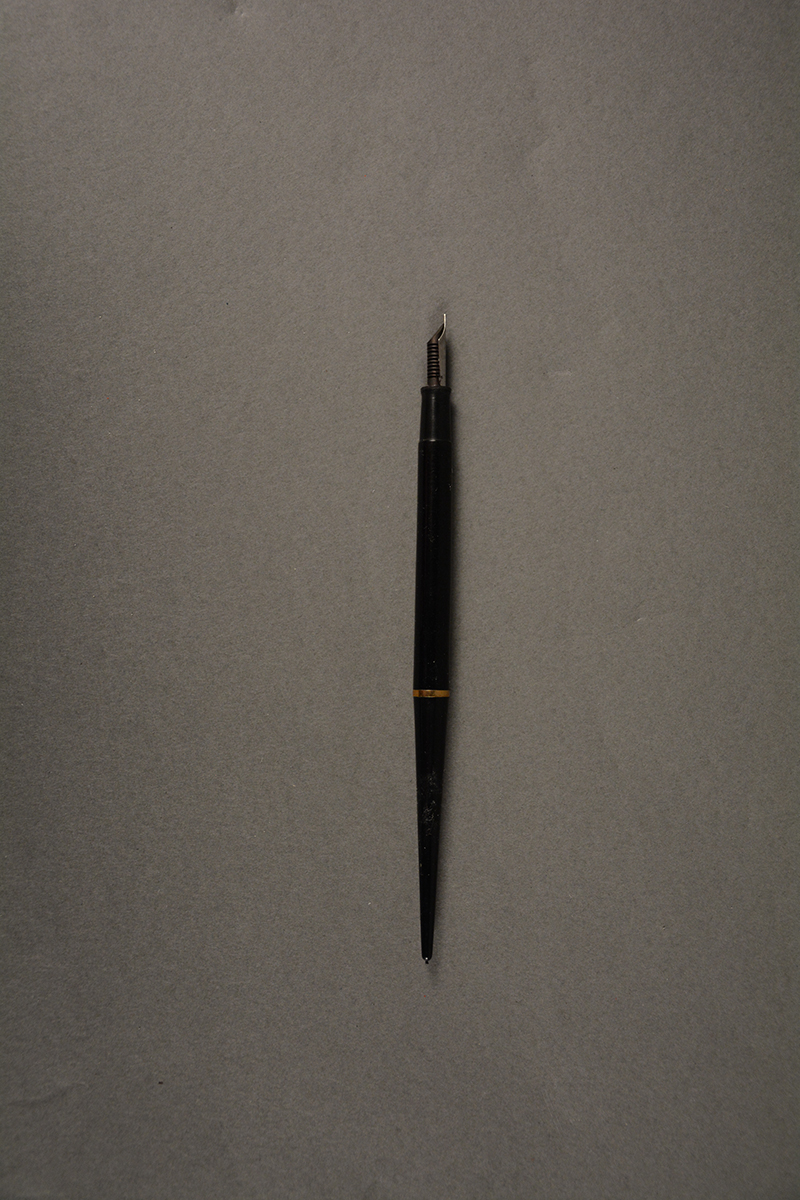

Fulton’s interest in space and space technology grew out of Cold War events and his diplomatic work. In 1959, while working at the U.N., Fulton was made a congressional advisor on the U.N. Ad Hoc Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. He helped represent Congress in negotiations for a treaty aimed at preventing nuclear weapons from being used in space. When Lyndon Johnson signed the Treaty in 1967, Fulton received one of the commemorative pens he used. “Congressman Jim” was an original member of and eventually the ranking Republican on the House Committee on Space, Science, and Technology, which he used to bring money for space technology back to Western Pennsylvania. At various times, he headed the Manned Spaceflight and NASA Oversight subcommittees, which gave him direct access to the U.S. space program. His time there also gave him a unique opportunity for constituent service, bringing some of the space race’s generous funding home with him, to be used for research and industry.

From the time he was elected in 1945—when he was still deployed in the South Pacific—until he died in 1971, “Congressman Jim” cultivated a reputation of being what his obituary described as “a hand shaker par excellence.” He referred to himself as a “progressive” Republican rather than a liberal one who, in 1969, “took pride” in getting a perfect score from the AFL-CIO for his votes on economic issues. In a district with a majority of Democrats, he kept a close eye on what his constituents expected from him. Through his work on the Space and Aeronautics committee, Fulton was credited with bringing $1,500,000 for Pitt’s Space Research Coordination Center (SRCC) Building and directing federal money towards scientific development at the university. Research sparked innovation, which would in turn help create jobs. The SRCC had precisely this purpose, according to Pitt Chancellor Edward Litchfield: “to ‘spin off’ laboratory developments wherever possible into manufacturing operations” useful to regional industry.

When Fulton suggested budget cuts, they were aimed at giving his constituents a competitive advantage. In 1967, Fulton helped cut NASA appropriations for the post-Apollo Moon program by almost 50 percent, which on its surface seems to contradict his advocacy for space technology development. The thing is, he vocally criticized government pre-spending on manufacturing, which he said “shut out” Westinghouse’s development of the next generation of rockets[1]—the NERVA program, which attempted to adapt nuclear submarine propulsion for long-distance space travel. Fulton used every opportunity he could to advocate for education and jobs training in the region as the way to continue being competitive, and he called for Pittsburgh business to diversify into more fabricating and electronics for “supplementing its basic metals manufacturing.” He got federal funding spread throughout the region.

Fulton seems to have been genuinely excited by the possibilities of space. He hoped to be the “first congressman to land on the moon,”[2] and he thought the weightlessness of space could help save people with heart troubles. Perplexingly, he even “proposed launching giant umbrellas and mirrors into space to control the weather…This would mean a saving in electric bills . . ..”[3] As a congressman, he harnessed his excitement for space and worked to bring the Space Race’s opportunities home—federal spending on science and development, technology to diversify the Steel City’s economy, and an appreciation for science manifest in grants to the region’s universities. When Fulton died of a heart attack in 1971, federal buildings in Washington flew their flags at half-staff for this hometown supporter of space exploration.

Alexander Kurland is a 2018 curatorial intern with the Heinz History Center’s museum division.