A commitment to innovation and a willingness to fund new ideas has made Western Pennsylvania a center for innovation.

Regional industries supplied settlers going West, armed the Union Army and the Allies of WWII, and left their marks on the built landscape of the nation. Individual and corporate leaders encouraged research and development that fed future technological development.

From the Wright brothers to the Apollo mission, new ideas from this region played a crucial role in the country’s technological advancement.

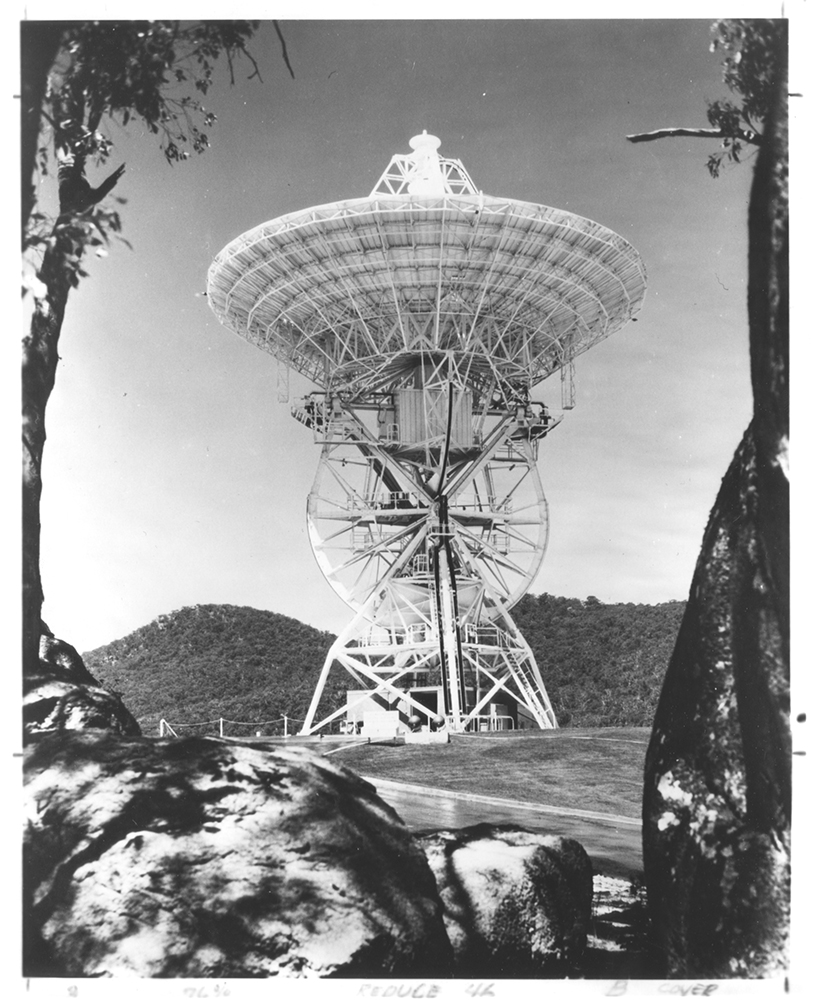

Alcoa supplied more than a million pounds of the specialty aluminum alloy 2219 for the Saturn V rocket alone, but many other Pittsburgh companies and experts contributed to the nationwide effort to fulfill Kennedy’s mandate to put a man on the Moon and bring him safely back to earth before the end of the decade. Some companies, such as North American Rockwell, Alcoa, and U.S. Steel, made major contributions to the space program, but were so large and diverse by the 1960s that they had factories all over the country. A lot of the work happened outside the region, but much of the research and development that contributed to the program happened here.

In addition to Alcoa, other companies and inventors first came to Pittsburgh seeking financial support or the assistance of established industries. Like Charles Martin Hall of Alcoa, Colonel Willard Rockwell came to the region to do business with the Mellons. After starting a successful bearing and axle company in Wisconsin, the Colonel took over the Westinghouse-owned Equitable Meter Company in 1921 at the request of the Mellons. Equitable eventually merged with his other concerns to create Rockwell International. In the 1960s, at the height of the space program, Rockwell bought the struggling North American Aviation based in California. North American had the contract for the majority of the Saturn V rocket, including the Second Stage, the Service Module, Command Module, Launch Escape Tower, Launch Escape System, and the rocket engines for all stages, including the smaller engines that steer the spacecraft in space. As Rockwell once said, “If it moves, we probably made something on it.”

But it wasn’t just major contracts: Many small Pittsburgh manufacturing firms were subcontractors for the Saturn V, Command, and Lunar Modules. In a Pittsburgh Press insert on the Moon mission, some of the local companies who are often not credited with being a part of the space program are highlighted.

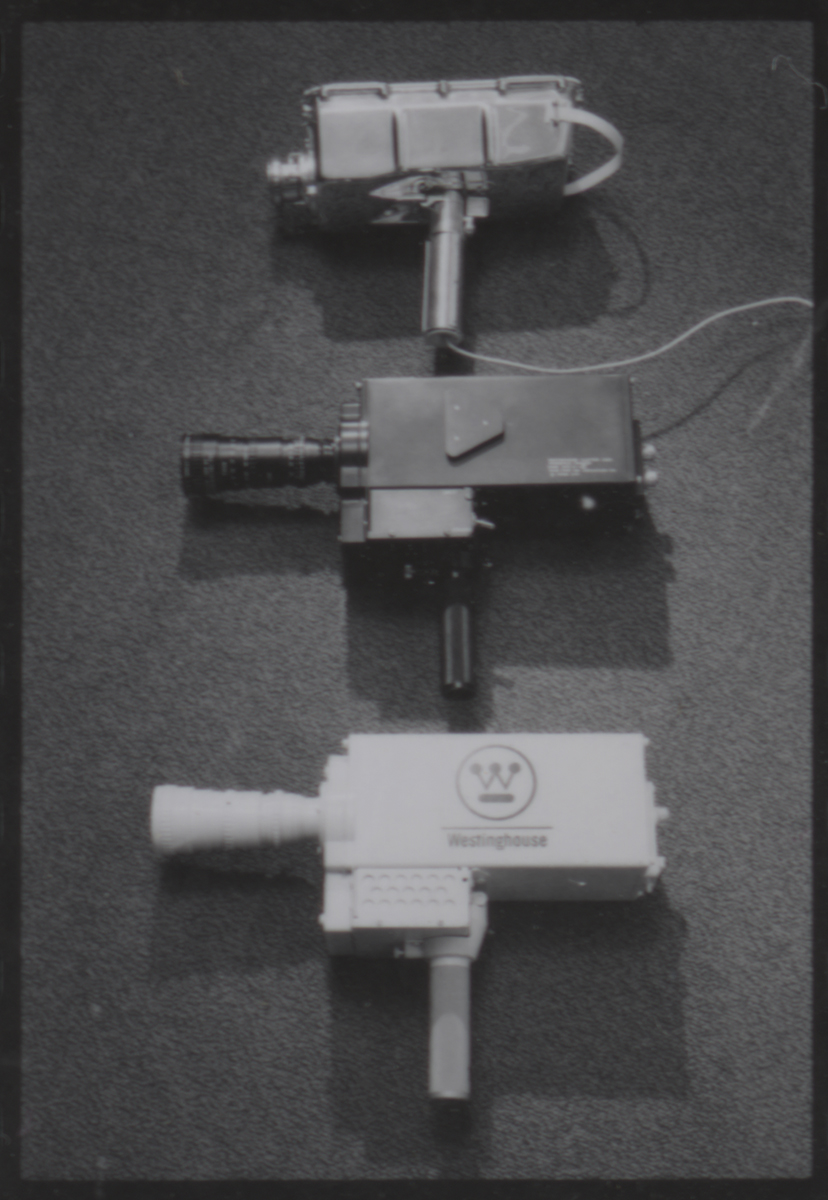

Westinghouse received a $2.29 million contract in 1964 to create a camera that could operate on the surface of the Moon, handling its temperature extremes and low lighting, while being operated by an astronaut wearing a bulky spacesuit. The final result weighed only seven pounds, crucial in an industry where every pound mattered. By pulling a lever as he exited the Lunar Module Eagle, Armstrong triggered the camera to record his historic first steps on the Moon. The innovative Secondary Electron Conduction video tube developed by Westinghouse Electric allowed the camera to operate in the low light of the Moon. The Apollo 11 camera that recorded those historic first steps remains on the Moon. Westinghouse eventually developed three cameras for the Apollo space program.

Detre Library & Archives at the History Center.

The list includes the Edwin Wiegand Company (now Chromalox), Bacharach Industrial Instruments Company, J.P. Devine Manufacturing Company, Pressure Chemical Company, Griff Machine Products Company, Mine Safety Appliance Company, PPG Industries, Allegheny Ludlum, Cyclops, and Crucible Steel.

Chromalox developed a strip heater that kept the electronic control box on the Lunar Module at a temperature that insured the fuel triggering device could function.

The Bacharach Company made devices that tested air quality and developed electrical systems, either of which may have been used on the Command and Lunar Modules.

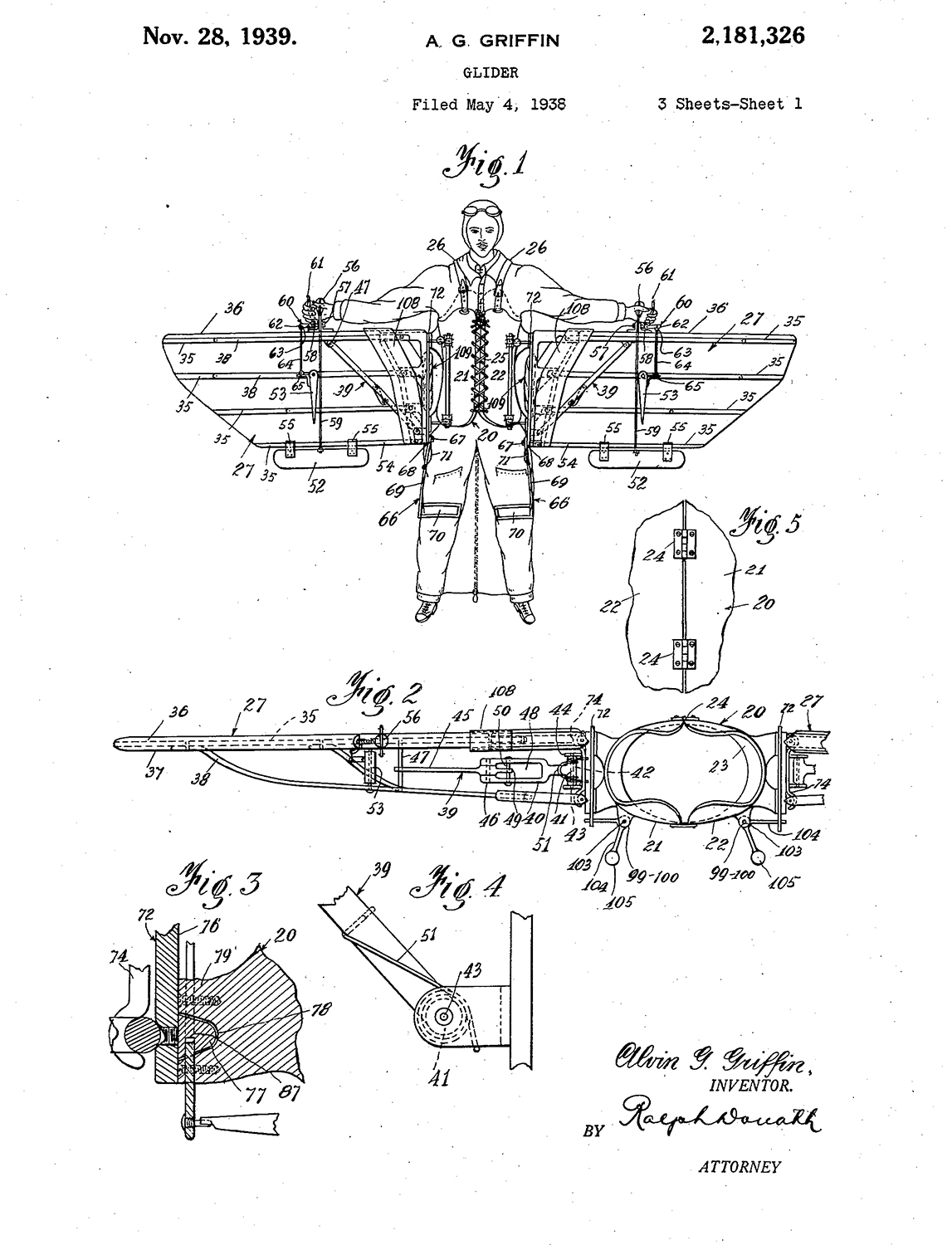

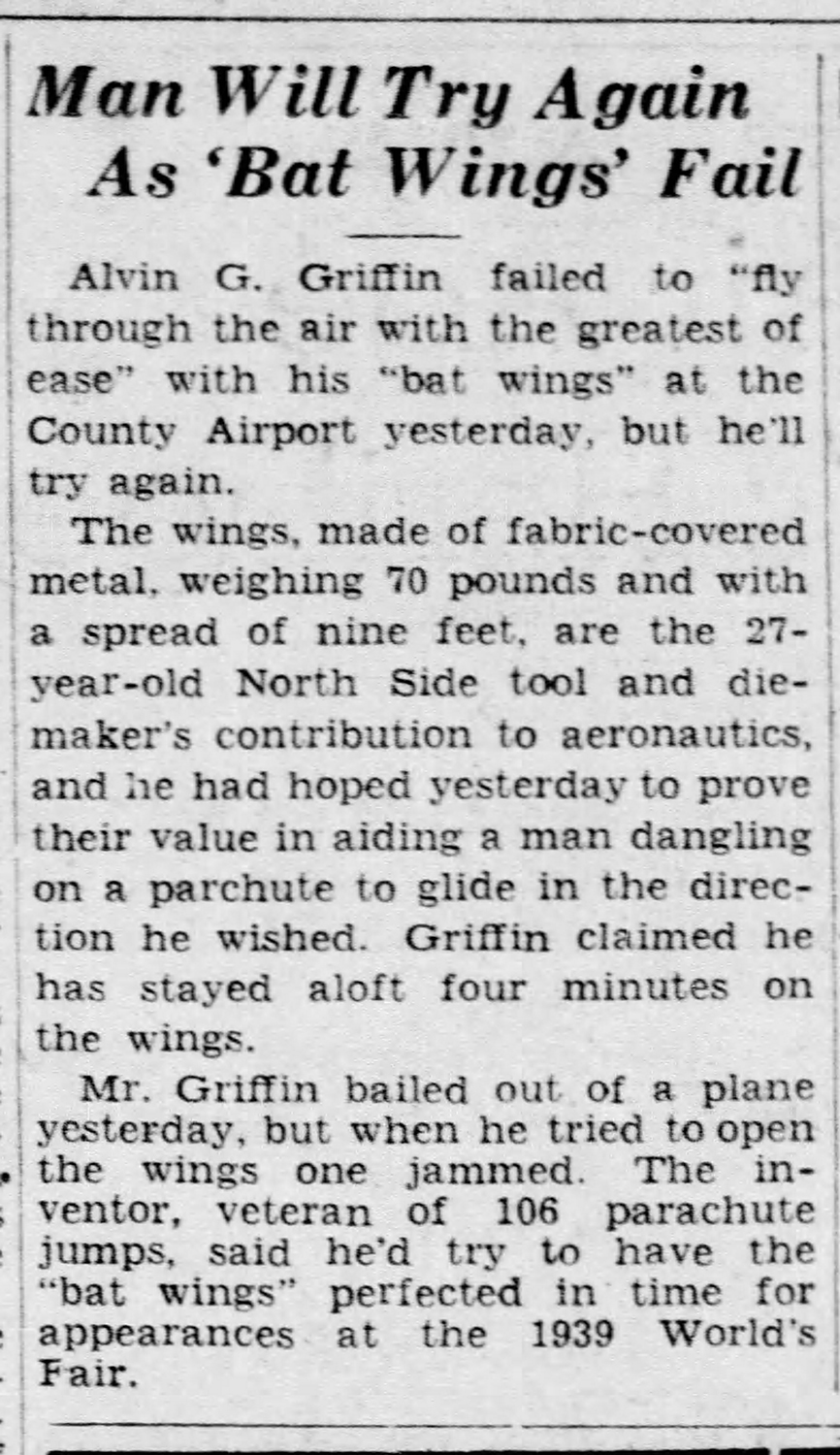

Griff Machine Company of East Liberty had a machine patented by its founder Alvin G. Griffin that NASA used to test the strength of steel alloys used on the Saturn V.

P. Devine, located in Lawrenceville, was a metal fabricating company that made autoclaves, essentially a large pressure cooker that tempered the metal for the extremes of space. This was key to manufacturing the metal honeycomb structure that covered the Command and Lunar Modules.

Allegheny Ludlum (today ATI), Crucible Steel, and Cyclops Corporation based in Titusville and Bridgeville, produced specialty metal alloys for the spacecraft.

The Pressure Chemical Company, which was founded in 1964 in Lawrenceville, made a paste that was used to insulate the Command Module for the heat of reentry. In the late 1960s, they were one of the few places in the country that made these specialized materials.

MSA invented a canister that provided astronauts with an emergency oxygen supply and one that absorbed excess carbon dioxide, as well as a filtration system that prevented the spread of any Earth contaminants to the Moon. PPG made glass for the Command and Service Modules. Another Western Pennsylvania company, Snap-Tite in Union City, made quick disconnect couplings for the Saturn V second stage.

There were an estimated 20,000 companies and 400,000 people in the United States that played a part in getting a man on the Moon. Pittsburghers can be proud of the vital role played by the industries and people from this region.

Emily Ruby is a curator at the Heinz History Center.