The following article originally appeared in the Spring 2010 edition of Western Pennsylvania History.

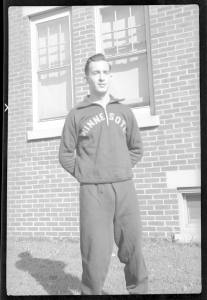

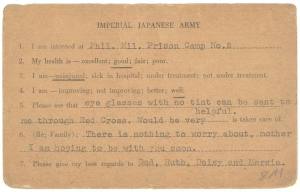

Among the more unique forms of correspondence in the collections at the Detre Library & Archives are the prisoner of war cards sent by Lt. Arthur H. Buchman to his family in Pittsburgh during World War II. About the size of a postcard, the cards were Buchman’s only means of communicating with loved ones back home following his capture by the Japanese in May 1942. Part of the Rauh Jewish Archives, the Buchman Family Papers contain six of these cards, as well as letters sent by the Army lieutenant in the months prior to the outbreak of the war.

In September 1941, just a few months after enlisting in the army, Buchman boarded a ship for the Philippines. In letters to his family he described the voyage, which included a quick stop in Hawaii and an encounter with an intense tropical storm. Strict blackout rules were in effect on the ship due to unfriendly submarines thought to be lurking nearby. Buchman wrote that any soldiers “…caught smoking, lighting a match, a light, etc. are arrested and confined to quarters for the rest of the trip.”

After arriving in Manila, Buchman was assigned to Fort Hughes on Caballo Island, close to the island of Corregidor in the Manila Bay. The fort, along with several other military strongholds in the area, was established to defend the entrance to the bay. It was heavily armed and well supplied, intended to withstand a possible attack for a number of months. Buchman’s letters during this time reveal increasing preparations for a potential military conflict:

“… things are getting very serious around here. For the first time the majority of the officers are expecting hostilities at any hour. Where from or how, I don’t know. But we are ready and will be awfully tough to lick.”

After November, just weeks away from the attack on Pearl Harbor, the letters stop. On Dec. 29, the Japanese began their bombardment of the forts in Manila Bay. When the Buchman family next heard from their son, it was through a prisoner of war card.

The cards, most of which are undated, contain preprinted sentences that describe the prisoner’s basic physical condition and allow for short messages to be typed. On the reverse side, a large stamp reveals that the card had been examined by U.S. censors. While most of the cards list Buchman as “well” or “good,” a couple state that he is “under treatment,” though further details are not included.

In his short messages, Buchman tried to reassure his family that he was safe. “Mother and Dad don’t worry about me,” reads one. “This is just like laying around in Aunt Sally’s cottage,” is typed on another. “Plenty of rice and vegetables like I planted before I left.”

Any outright mention of the hardships Buchman undoubtedly endured as a prisoner of war would have likely raised the attention of Japanese censors. However, in one card, Buchman requests his family to give his regards to the oddly named “George A. Gainchang.” Possibly a veiled reference to “Georgia chain gang,” this might have been an attempt by Buchman to convey the true nature of his experience.

Tragically, Buchman did not live to see freedom. On Jan. 9, 1945, he was killed while aboard the Enoura Maru, a Japanese ship transporting POWs from the Philippines to Japan. The ship, which had no markings signaling that there were POWs aboard, was bombed by Allied forces while docked in Taiwan.[1] Buchman was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and Silver Star.

[1] William B. Breuer, The Great Raid on Cabanatuan: Rescuing the Doomed Ghosts of Bataan and Corregidor (New York: J. Wiley & Sons, 1994), p. 151.

Matthew Strauss is the chief archivist at the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.