A version of this article originally appeared in the Winter 2013 issue of Western Pennsylvania History.

“Attached is a copy of a letter,” begins a piece of correspondence in the Ray Sprigle Papers and Photographs, “which is the latest of many efforts made by us to expose one of the most heinous acts within the imagination – the swindle of a citizen by his government.” The letter is one among many in the collection sent to Sprigle, a former investigative reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, during the 1950s. Other letters detail a wrongful commitment to a mental hospital, ties between public officials and organized crime organizations, and a neighborhood speakeasy operating within full view of the police. Often unsigned and sent in envelopes without return addresses, the writers had entrusted their stories Sprigle, rather than the local authorities, with the hopes that he might take up their cause.

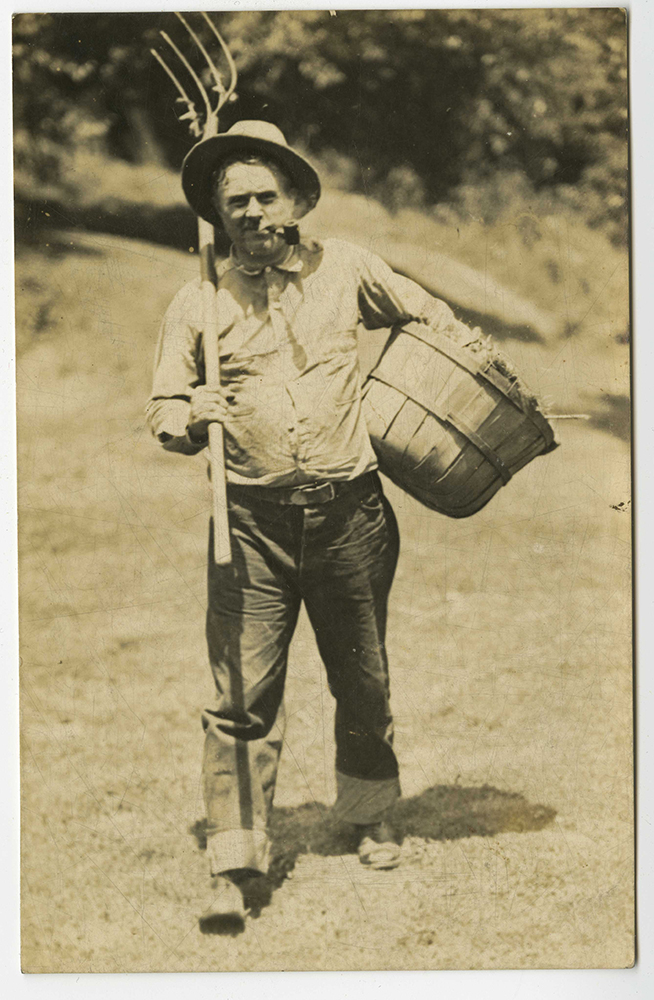

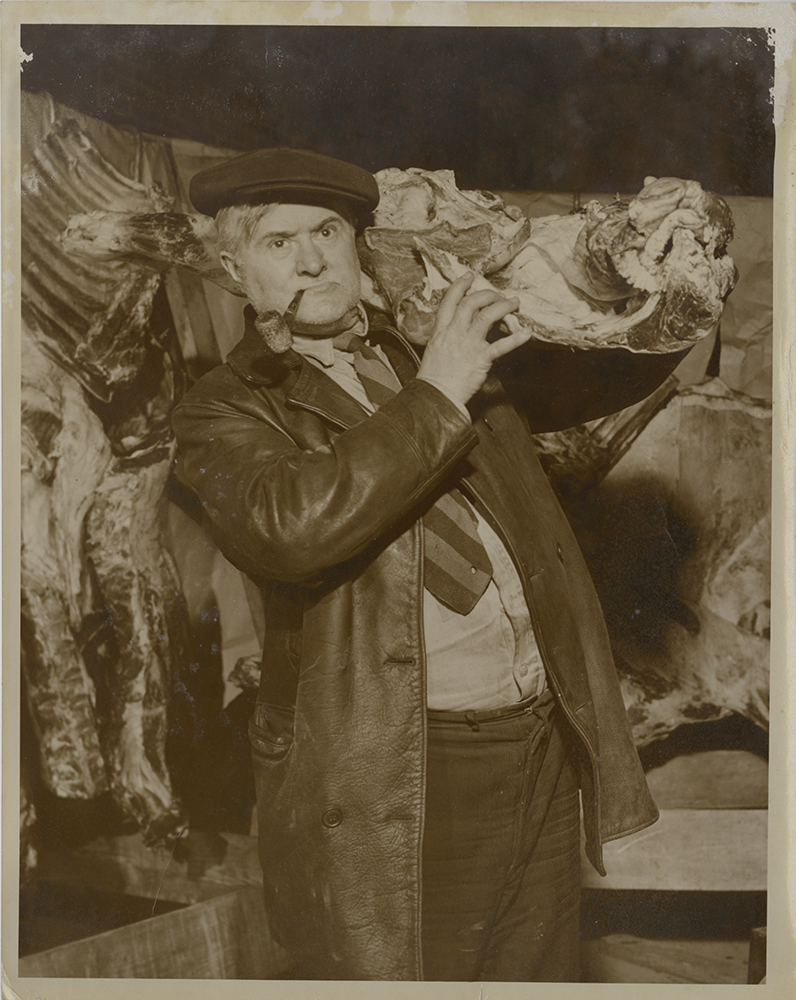

By the 1950s, the colorful and opinionated Sprigle had cemented his reputation as a reporter willing to fight for the underdog. A reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette since the paper’s inception in 1927, Sprigle wrote exposés on conditions in mental hospitals and coal mines, illegal gambling operations, and the black market for meat during World War II. Sprigle often went undercover in pursuit of his stories, donning disguises and assuming bogus identities.

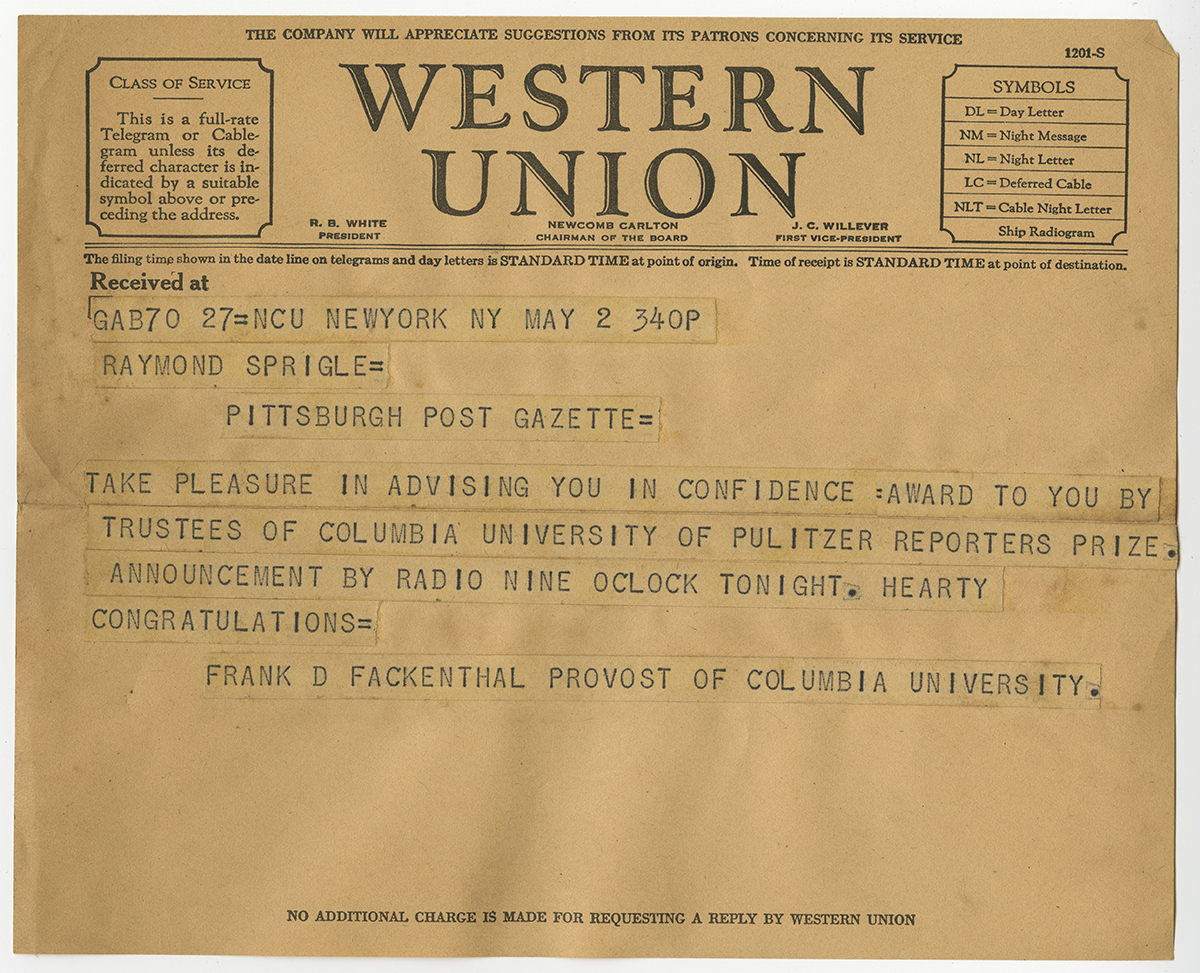

In 1937, Sprigle landed on the front pages of newspapers across the country when he broke a story about ties between Hugo Black, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s nominee to the Supreme Court, and Ku Klux Klan. Acting on a tip from Paul Block, the publisher of the Post-Gazette, Sprigle had flown to Black’s home state of Alabama where he met with James Esdale, a former Grand Dragon in the KKK. Reluctant to speak about the matter at first, Esdale became more forthcoming after Sprigle discovered the two shared an interest in raising chickens. Esdale would eventually turn extensive documentation proving Black’s membership in the group. [1] While the news didn’t ultimately prevent Black from serving a long career as a Supreme Court Justice, it did lead to a Pulitzer Prize for Sprigle, the first for a Post-Gazette reporter.

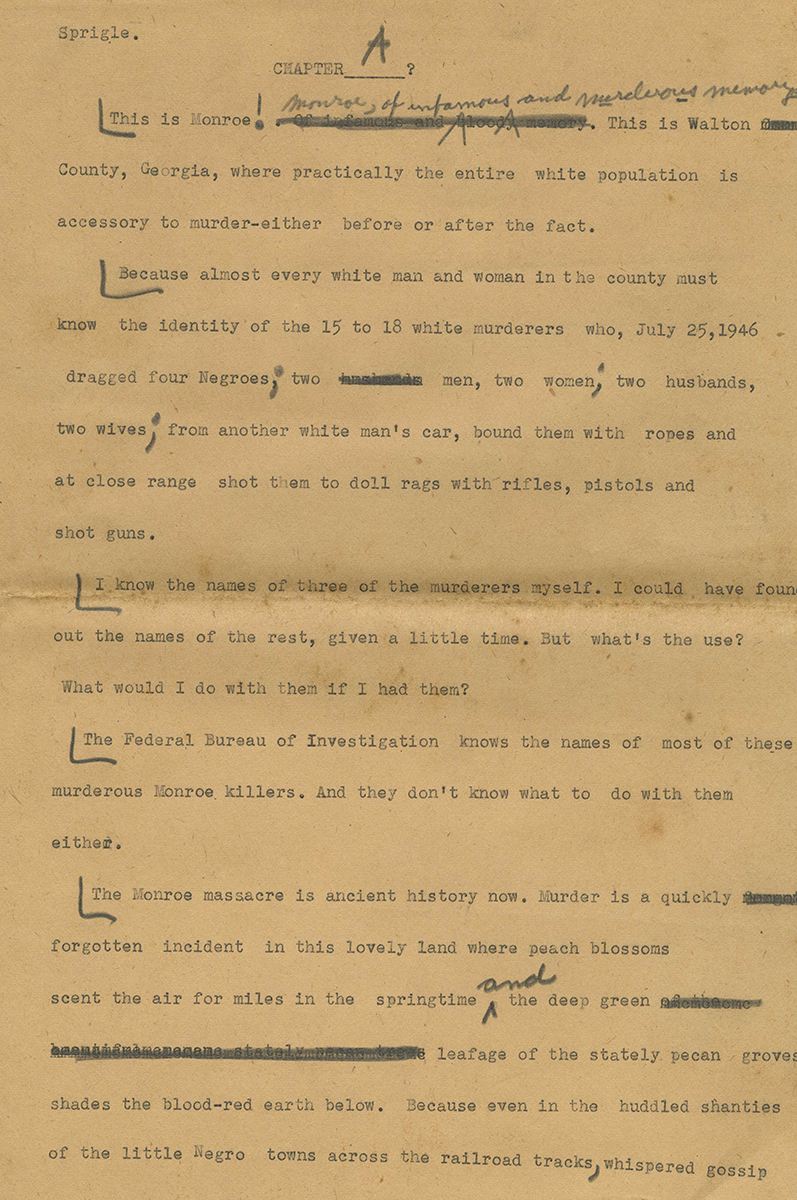

Sprigle would garner national attention again in 1948 with a series of articles titled “I was a Negro in the South for 30 Days,” which shed light on the Jim Crow conditions that African Americans living in southern states were forced to endure. To research the stories, Sprigle disguised himself as an African American and was escorted through the South by J.W. Dobbs, a well-known Civil Rights leader from Atlanta. The trip provided Sprigle with an opportunity to experience racial segregation first-hand. The resulting 21-part series, which was published by Post-Gazette and syndicated by over a dozen other newspapers, ignited a debate about an issue that had been little understood in the North.[2]

Along with letters from the public, Ray Sprigle Papers and Photographs also contain Sprigle’s notebooks, research material and drafts of articles, providing a glimpse into the reporter’s writing process. Donated to the Heinz History Center’s Detre Library & Archives by Sprigle’s daughter Rae Jean Kurland, the collection also includes images of Sprigle in undercover disguises and on his farm in Moon Township. This collection is one of over 500 collections that has been described and cataloged through a Basic Processing grant from the National Historical Publications and Historic Resources Commission.

Sprigle continued writing until his death at age 71, a result of a car accident while he was coming home after covering a conspiracy trial in New Castle, Pa. Following his death, George M. Leader, then the governor of Pennsylvania, issued a statement commending the reporter’s “great sense of moral indignation,” mentioning that Sprigle’s articles on mental hospitals had led to reforms throughout the state.[3]

[1] Roger K. Newman, Hugo Black: A Biography, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1994), pp. 247-249.

[2] Bill Steigerwald, “Sprigle’s Secret Journey,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed Sept. 11, 2013.

[3] “Tribute Paid Sprigle By City, State Leaders,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 24, 1957.

Matthew Strauss is the chief archivist at the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.