The Eric Moses papers, while not quite as enigmatic as the Marcia Robbins papers (read part one), also speak to the difficulty in arranging Jewish emigration from Germany and other European countries. While Marcia escaped Russian- and Japanese-occupied China before the outbreak of World War II, Eric Moses was working to get Jews out of Germany during the height of Hitler’s power.

Eric (born Erich) Moses was born in Germany on April 8, 1890, the son of Louis Moses and Doris Lilenthal Moses. He had two brothers, Ernst and Georg. He attended school at King School in Berlin from 1896 to 1907. Moses worked for Orenstein & Koppel, a major German engineering company starting in 1908 and, in August of 1913, he emigrated to the U.S. as an employee for the Orenstein & Koppel Co. in Pennsylvania. Eric Moses worked for Orenstein & Koppel until 1916 and received training as an accountant. In the following years, Moses provided accounting services for organizations such as Kaufman & Baer’s Department Store, the Anglo-American Company, and the O. Hommel Company. In 1921, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen and married Lilian York, the daughter of Joseph and Katherine York, in Cuyahoga, Ohio. The couple had one daughter, Doris Moses, born September 5, 1926.

As a successful businessman with international contacts, Eric Moses facilitated the escape of family members, friends, and other Jews from Nazi Germany. He was aided in his efforts by Julius Huettner, the Swedish Consul to Costa Rica and a cousin of Lilian York Moses. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Moses’s Squirrel Hill home served as sanctuary for newly-arrived German Jews.

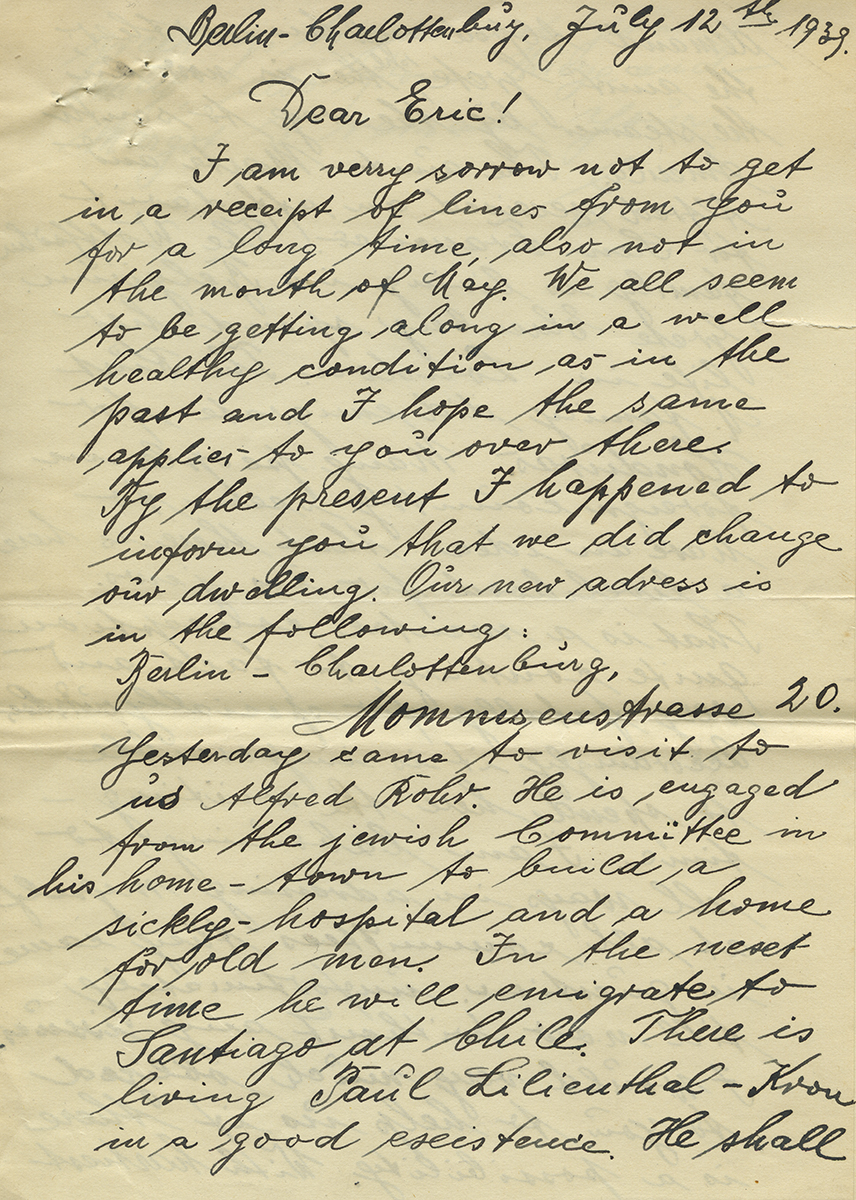

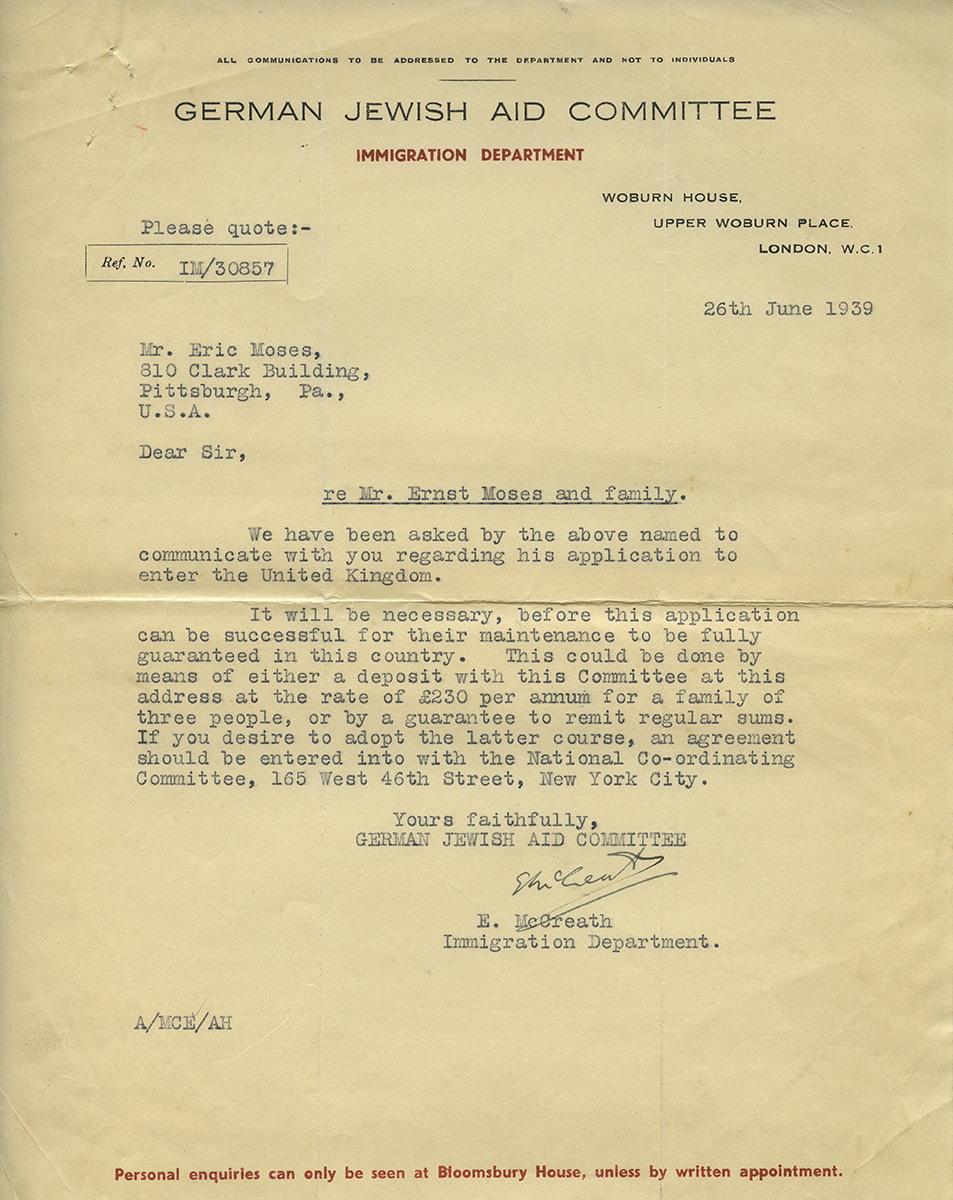

In Moses’s letters to and from his brother Ernst, still in Berlin with his family in 1939, you get a sense of the global scale of Jewish displacement that was a consequence of the Nazi regime. In a letter dated July 1939, Ernst updates his brother on where their friends and families are. Their locations range from as close as Belgium and London, to as far afield as San Francisco, Calif, to Chile and Honduras. Ernst and his family have had to move yet again, but remain in Berlin. Eric sent Ernst a form letter that he could send on to Julius Huettner in Sweden, as Eric has been unable to pay the fees to the German Jewish Aid Committee necessary to bring Ernst and his family to the U.S.

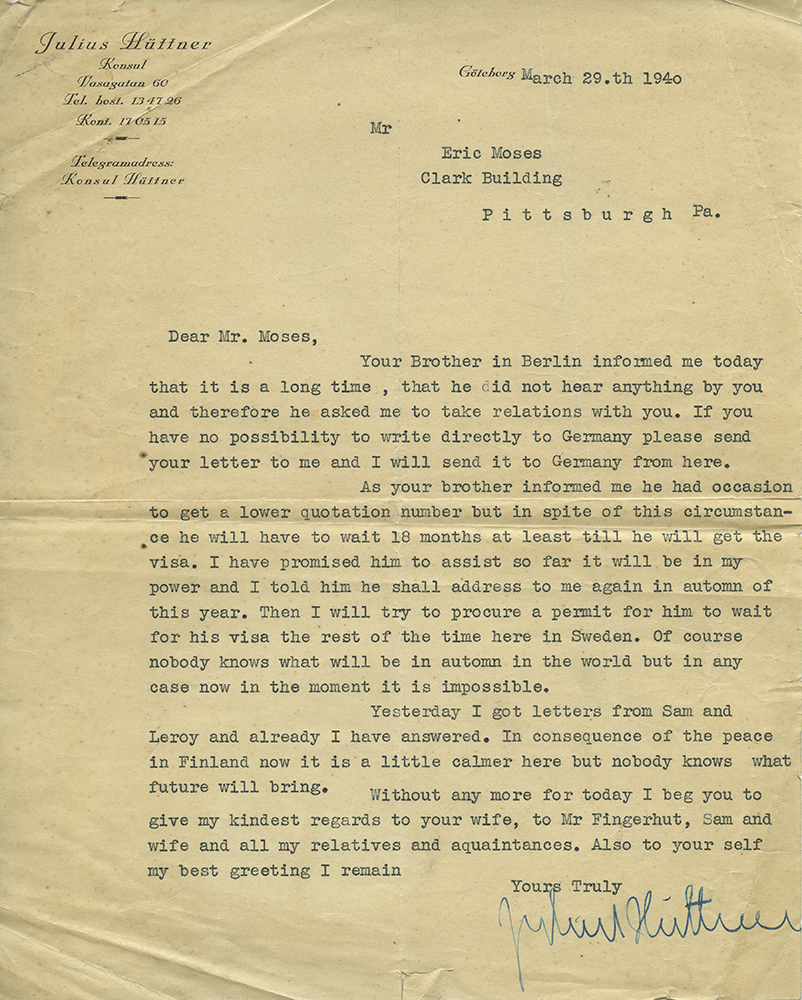

As conditions in Germany further deteriorated, Julius Huettner in Sweden became the go-between for the brothers, as Eric Moses was unable to send mail from the U.S. directly to Germany. Huettner’s letter from March 1940 described his role relaying the communications between Pittsburgh and Berlin. However, according to the material available to us in the Moses Collection, Ernst’s letters ceased that same year. Given Ernst’s silence in the scrapbooks the follow, it is unlikely that Eric Moses was able to help his brother and his family escape.

Eric Moses, together with Julius Huettner, was successful in helping other families flee Germany, and he kept in contact with friends and family long after the war had ended. Eric corresponded with friends Hans “Juan” Kron, who ended up in Costa Rica, and Max Marcus, who immigrated to New York, into the 1950s.

Both the Moses Collection and Robbins Collection illustrate the scope of the Jewish diaspora before and after WWII and the challenges that Jewish families faced in attempting to reunite with their loved ones in the U.S. and elsewhere.

In many ways, working with these collections has given me a sense of déjà vu, given the refugee crisis taking place in our present day. That is one of the more powerful, and at times upsetting, aspects of working in the Rauh Jewish Archives. In piecing these stories back together, the tragedies of the past are given new voice and call us to account once more.

As the Detre Library & Archives’ “Pitt Partner” intern, Kara Flynn processes many of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives’ incoming collections. This summer, Flynn will be graduating from the University of Pittsburgh with a Master’s degree in Library & Information Sciences.