If you bought a box of matzah for Passover this year, it probably came from the grocery store. And the grocery store probably got it from a bakery based in New York or Israel.

But a century ago, many Jewish families in Western Pennsylvania purchased their matzah locally. Caplan Baking Company was one of the biggest and best-known Jewish bakeries in the region. Breads, cakes, and other baked goods from its factory on Logan Street in the Hill District could be found in homes, delis, and restaurants all throughout this region.

Each spring, the bakery switched to matzah. Matzah is the central food of the Jewish holiday of Passover. The flat, unleavened bread commemorates the Israelite exodus from Ancient Egypt, a departure too sudden for the departing Jews to allow bread to rise.

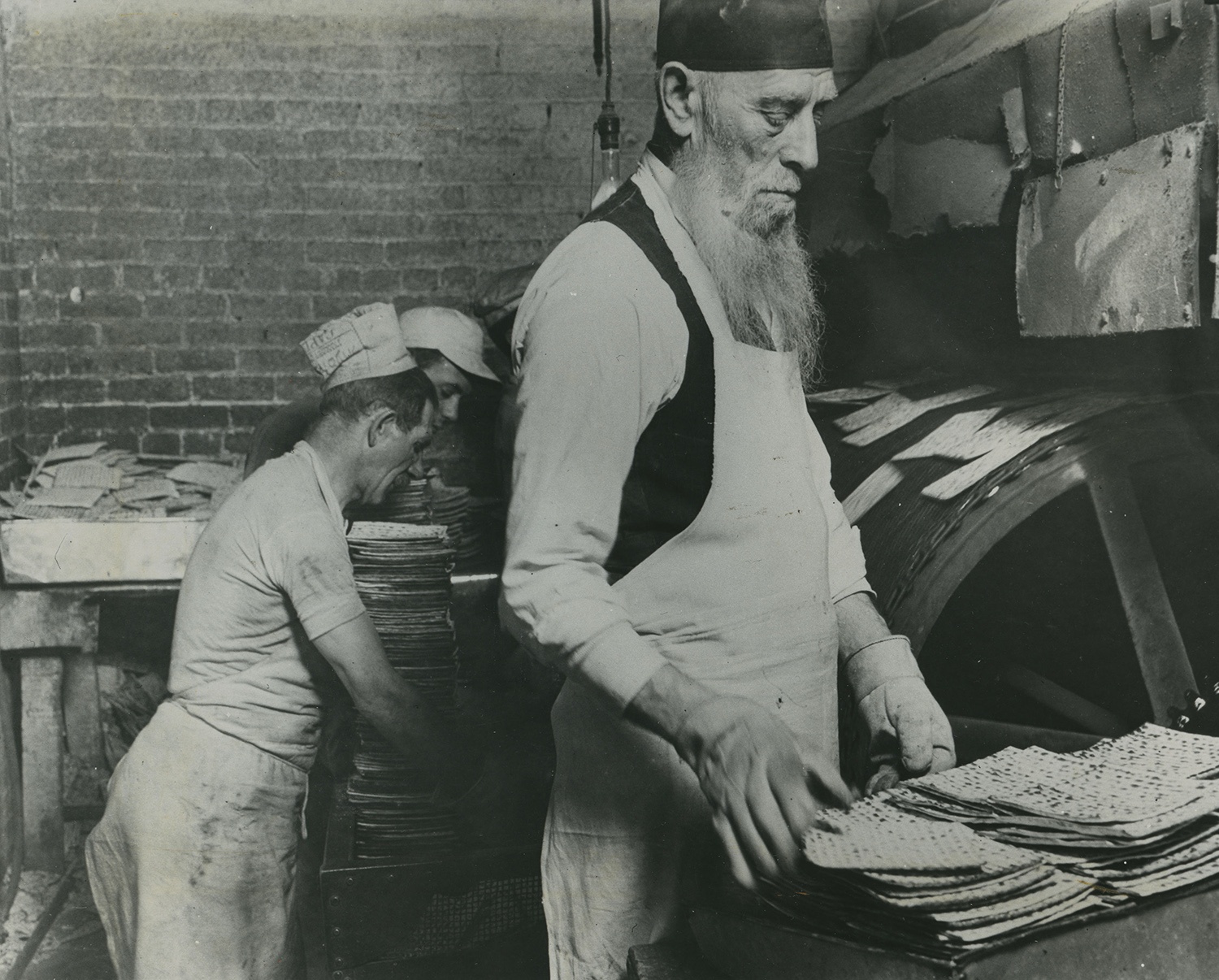

Matzah creation is simple. There are only two ingredients: flour and water. But matzah production is complex. It requires precise conditions at every point in the supply chain, starting with the wheat harvest. Each spring, the Caplan Baking Company mashgiach (food inspector) Jacob Radbord would spend several days in Red Lion, Pa., in eastern Pennsylvania, overseeing the grinding of flour to bring back to Pittsburgh. All throughout the season, he would monitor matzah production, ensuring that it met religious standards.

The Caplan Baking Company was founded in the early 1880s. At points, the company struggled against the perennial Pittsburgh prejudice against itself. Advertisements begged locals to buy matzah locally. “What Caplan Matzos are: the perfect matzos,” the company proclaimed in an ad from the time. “The thinnest, crispiest, tastiest, thoroughly baked matzos in the world.” And then, for good measure: “A famous Pittsburgh product.”

In the years following World War I, when the infrastructure of European Jewry was still rebuilding from the war, Caplan Baking Company became an important link for separated Jewish families. It found a way for Jewish families in Western Pennsylvania to send boxes of Caplan Baking Company matzahs to their families abroad for Passover.

Loyalty grew, turning the Caplan Baking Company into an important regional supplier of matzah. According to a profile in the Pittsburgh Sun Telegraph from 1929, the company shipped about one million pounds of matzah each spring under the supervision of Jacob Radbord. The number seems a little high, given the Jewish population of the region. But if the number is even close to correct, then the Caplan Baking Company was a primary supplier of matzah for Jewish communities throughout the northern end of Appalachia.

Caplan Baking Company survived through World War II but liquidated its Logan Street factory in the mid-1940s. In the years after the war, New York bakeries like Streit’s and Manischewitz increasingly cornered the American market on machine-made matzah, achieving economies of scale that pushed regional matzah bakeries out of the market.

What survives today is a photograph of Jacob Radbord inspecting matzah at the Logan Street bakery in the early 1930s. It is perhaps the best-known image in the Rauh Jewish Archives. To many people, it reflects a lost world. Although the custom of eating matzah is eternal in Jewish life, getting it from a local bakery has mostly become a memory.

Eric Lidji is the director of the Rauh Jewish Archives at the Heinz History Center. He can be reached at eslidji@heinzhistorycenter.org or 412-454-6406.