This story was originally published in the Fall 2018 issue of Western Pennsylvania History.

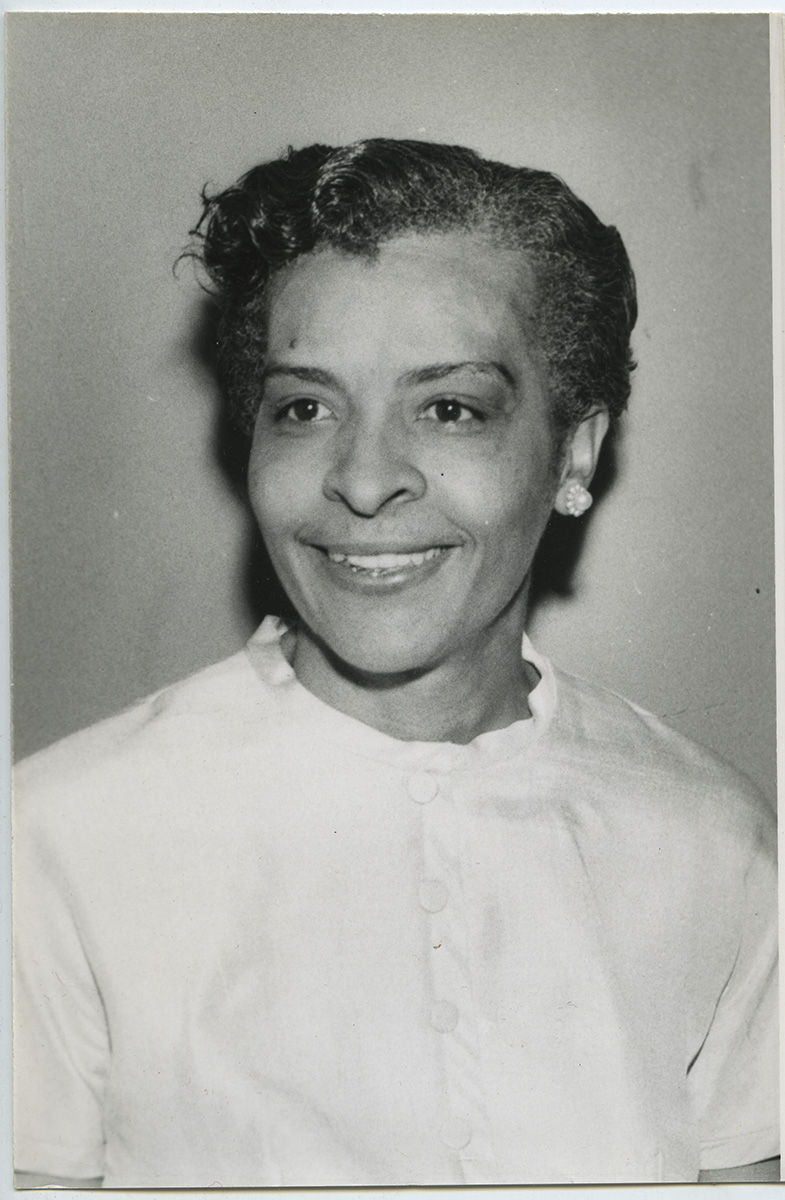

Tempted by the lure of being their own boss, many dream of opening a business. Few will follow through, perhaps warned off by statistics detailing the high percentage of businesses that fail within their first years. Maude Y. Hawkins took this risk, seizing the opportunity to create a better work environment for herself. A small group of archival materials held by the Detre Library & Archives documents the challenges faced by Hawkins as repercussions from tumultuous events placed obstacles in her path.

Raised in Philadelphia, Hawkins arrived in Pittsburgh in 1944 to work in the local branch of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. Founded in 1898 in Durham, the firm expanded in the 20th century to become the largest African American-owned insurance company in the country. Hawkins worked as the staff manager of the Pittsburgh office, the first woman to hold this post. She thrived in the position, winning awards and accolades from superiors. A letter sent by the vice president of the company reads “The Easter Division of the Pittsburgh District, under your supervision, comes in for HEARTY CONGRATULATIONS. We want to pass along our appreciation and thanks for the leadership you are furnishing.”

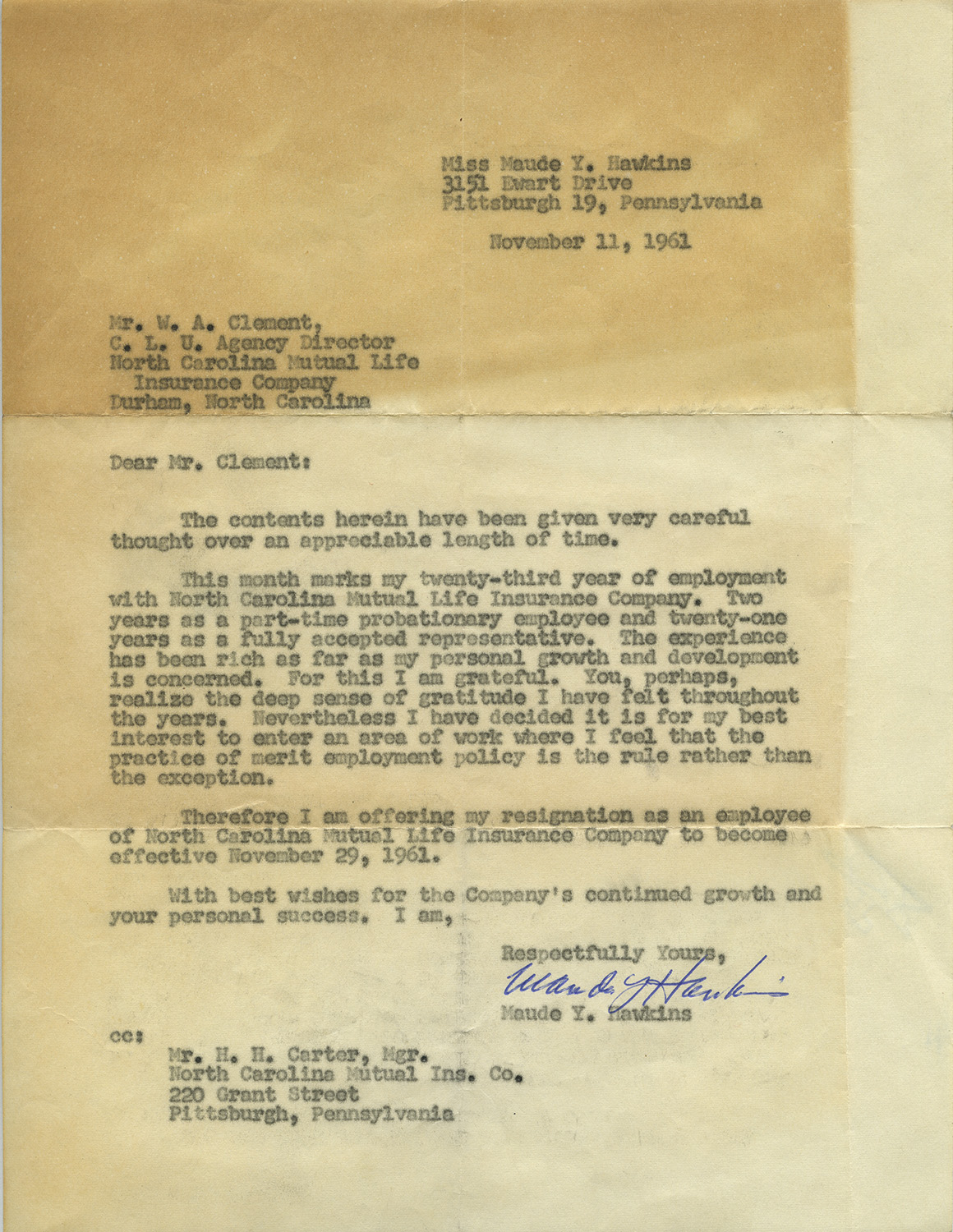

Despite these successes, Hawkins surprised her supervisors by abruptly resigning from her position after more than 20 years with the firm. While there is no clear indication of what prompted her departure, Hawkins wrote in her resignation letter that she wished to “…enter an area of work where I feel that the practice of merit employment policy is the rule rather than the exception.” Her reference to “merit employment,” a term that can refer to unbiased hiring and promotion practices, suggests that Hawkins believed inequality hindered her advancement in the company.

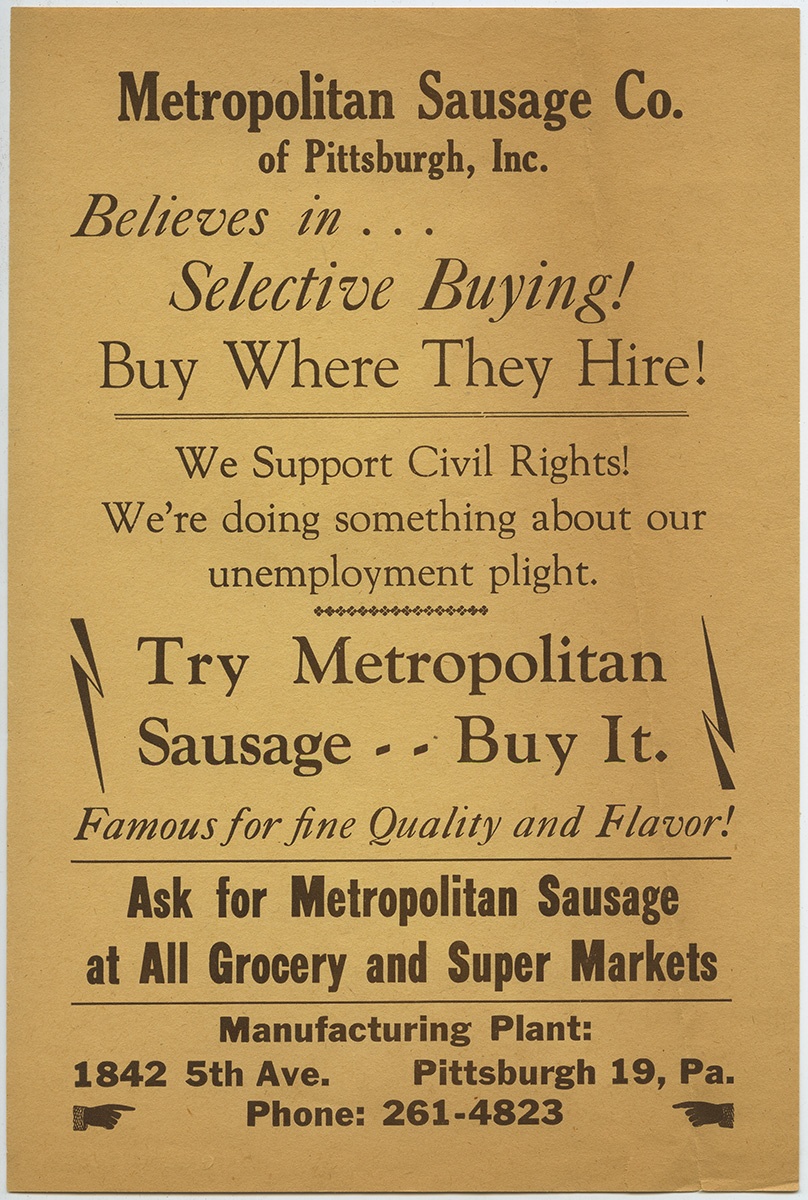

Striking out on her own, Hawkins became a major shareholder in the Metropolitan Sausage Company, a business established in the Hill District in 1948. Following a relocation of the plant to the 1800 block of Fifth Avenue, Hawkins began working at the business full-time, steering a revitalization of the then floundering enterprise. Finding her fellow shareholders unwilling to financially support her plans, Hawkins assumed full ownership of the company, relaunching it as the Hawkins Sausage Company in 1967.

patterned suit presenting certificate inscribed “North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance

Company…winner Miss Maude Hawkins…” to woman wearing dark suit with small flower or dot

pattern, in interior with map and large group photograph on wall, another version, c. 1957.

Maude Y. Hawkins Photographs, MSQ 171, Detre Library & Archives at the History Center. © Carnegie Museum of Art, Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive.

Loan application documents and correspondence reveal the challenges Hawkins faced as a small business owner in the Hill District during these years. Focusing on processing pork trimmings and beef navels into sausage rolls and links, the business prospered in its first year, counting stores in the Giant Eagle and Thorofare chains as customers. The 1968 riots that followed Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination left many of Hawkins’ clients damaged by fire and looting. In the aftermath, some of the white-owned outlets Hawkins sold to in the Hill District and Homewood subsequently left these neighborhoods.

As the business struggled to regain its footing, more setbacks occurred, including seven burglaries in the two years that followed the riots. Unable to procure insurance for the plant because of its location, Hawkins personally assumed the losses. In 1972, a fire took place in the second-floor apartment above the plant, forcing Hawkins to relocate to a new facility in Homewood to meet requirements set by federal and state food inspectors.

The 1973 oil crisis that wreaked havoc on the world economy put further stress on the Hawkins Sausage Company. In a letter sent out to her customers, Hawkins wrote that the crisis has resulted in “tremendous fluctuations in raw material and other costs” that had forced her to adjust her prices.” Two years later, the Hawkins Sausage Company closed its doors. In a letter to Pennsylvania’s Director of Bureau of Minority Business asking for assistance to restart her company, Hawkins wrote “…a general decline in the nation’s economy took its toll and I was one among many not big enough to survive.” Hawkins also corresponded with K. Leroy Irvis, the Hill District’s representative in the state legislature, thanking him for looking for potential investors. “I have and still am, making contact with persons whom I feel are sincerely interested in developing business owned by blacks,” she wrote. The following year, Hawkins completed a small business seminar held by the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Business. A workbook from the course reveals Hawkins developing strategies to revive her business, including transforming it from a sole proprietorship into a partnership.

The documents in Maude Y. Hawkins Papers trail off after the mid-1970s, suggesting that Hawkins failed to procure financial support to reopen her company. The collection was donated to the History Center shortly after Hawkins’ death in 1993 by Wendell Wray, a former professor emeritus of the University of Pittsburgh School of Information Sciences. Wray, who also headed the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture for two years, likely recognized value in ensuring that these records were preserved. Though not comprehensive, the collection offers a glimpse into the life of an African American woman who steered a business through a time of social and political upheaval.

Matthew Strauss is the chief archivist at the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.