As the world grapples with COVID-19, health officials are stressing the need for social distancing, contact tracing, and mass testing to curb the spread of the disease. Archival records from the Tuberculosis League of Pittsburgh, today known as Breathe Pennsylvania, shed light on how healthcare workers employed similar strategies to fight an earlier pandemic that swept across the world.

Like the coronavirus, tuberculosis (TB) is a respiratory illness that spreads through microscopic droplets in the air. The disease has claimed lives as far back as Ancient Egypt, but infection rates skyrocketed in the 19th century as TB found fertile ground among the cramped and unsanitary conditions of rapidly expanding cities. By the dawn of the 20th century, TB was a leading cause of death.

After losing his wife to TB, steel industry executive Otis H. Childs spearheaded the creation of the Pittsburgh Sanitarium in 1905. Operating out of a Hill District mansion donated by a local businessman, the organization represented the region’s first coordinated response to the TB pandemic. With government resources lacking, the Pittsburgh Sanitarium turned to the private sector for funding. Pittsburgh’s business leaders, including H.J. Heinz, Richard B. Mellon, and Henry Phipps, provided crucial support in the early years of the Pittsburgh Sanitarium. A few years after opening, the organization changed its name to the Tuberculosis League of Pittsburgh.

A common misconception about TB was that it was hereditary, leading many to not take precautions to avoid infection. To dispel misinformation about the disease, the Tuberculosis League sent nurses to the homes of TB sufferers to provide professional guidance about their condition. According to Tuberculosis League documents in the collection, this educational effort would be “…the most pressing and monumental field of work. It can only be accomplished by a personal crusade of corps of trained young women who will reach the people in their homes and conduct what are widely known as tuberculosis classes and form by far the most encouraging part of tuberculosis work.”

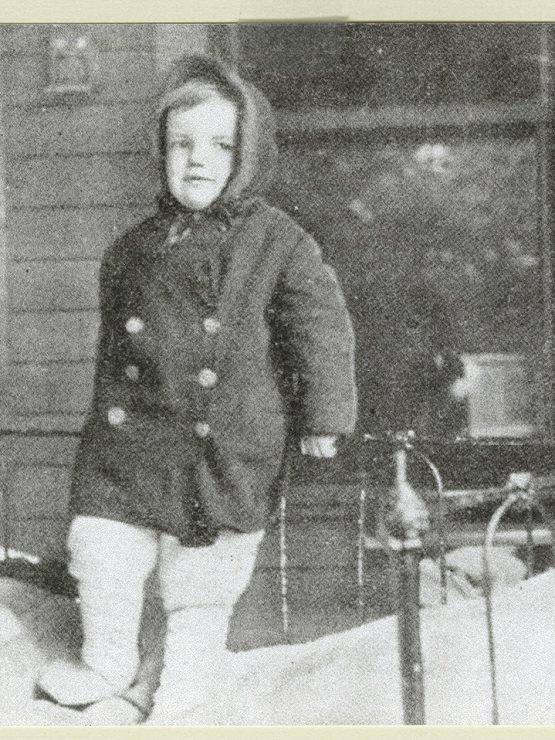

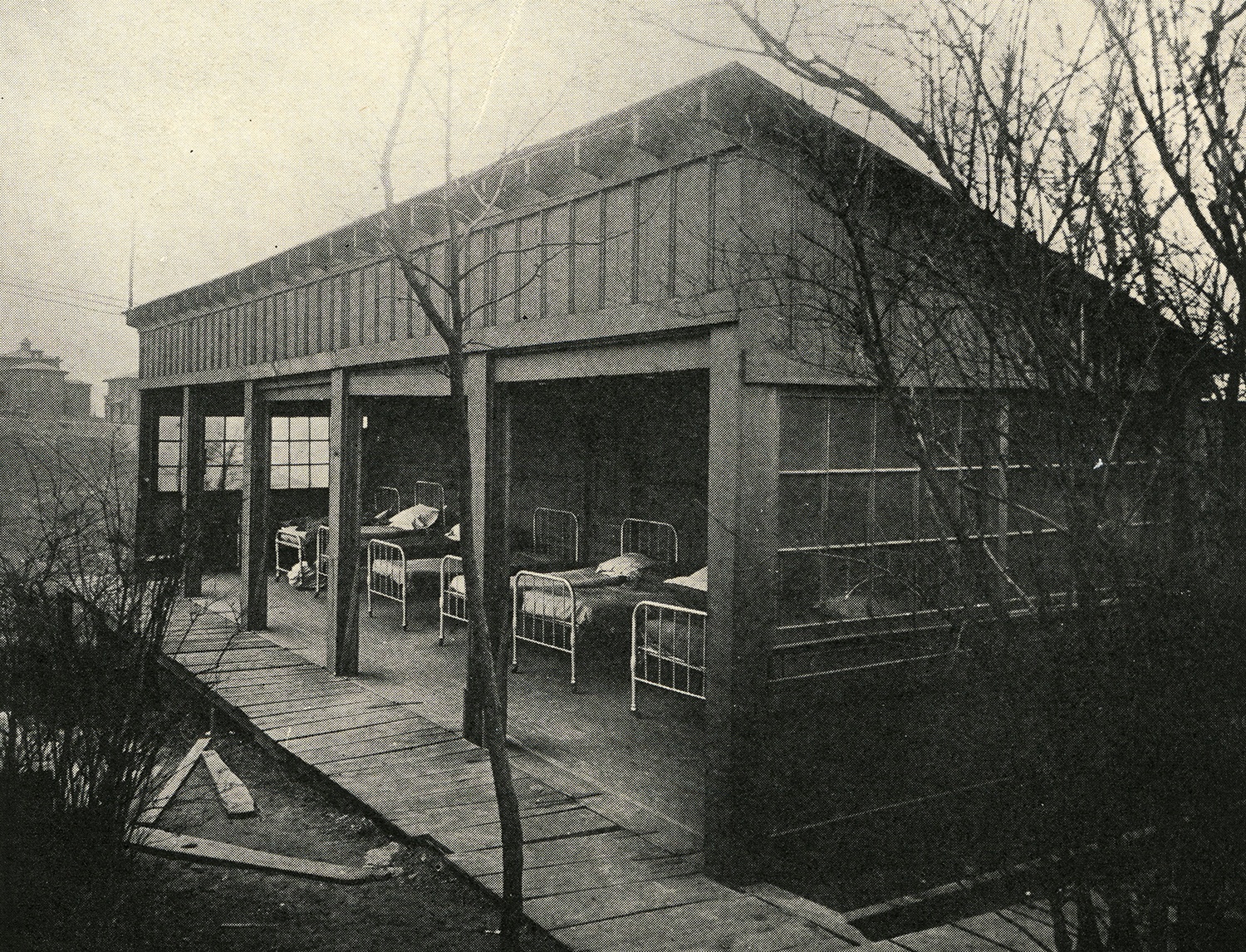

In its early years, the organization focused on providing rest, exercise, and fresh air to its patients. Reflecting a widespread belief that exposure to cold air was an effective method of treating the illness, the Tuberculosis League established an open-air classroom and sleeping quarters. Photographs from that era show beds in open-fronted shacks with the doors that were closed only in blizzards. Children in the open-air classroom sat at their desks with sleeping bags covering most of their bodies.

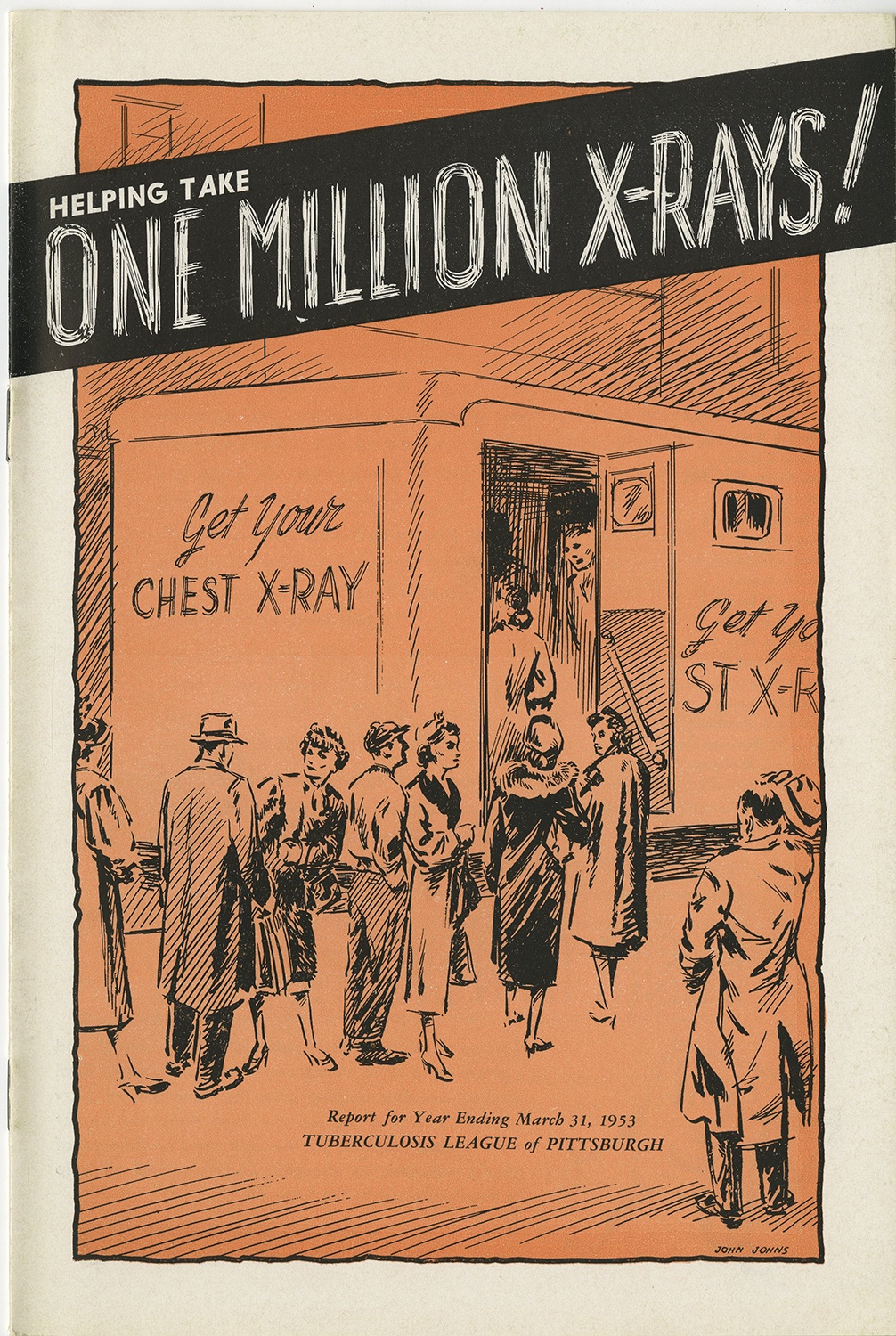

Though the cold air was an ineffective treatment, isolating TB patients in specialized facilities slowed the spread of the disease within the community. In 1929, the organization replaced the mansion with a purpose-built hospital building, which included space for new x-ray equipment that helped diagnose those with TB. In the 1950s, the Tuberculosis League coordinated, in partnership with the Pittsburgh Department of Health and other local organizations, mass testing of Allegheny County residents. Through this effort, nearly one million residents were examined for TB – the largest public health project that had been conducted in Pennsylvania. A newspaper advertisement promoting the project stated that the county would track TB patients for three years after their cure to ensure anyone suffering a relapse would receive medical attention.

Beginning in the 1940s, a series of antibiotics were developed that proved successful in the treatment of the disease. With these new drugs shortening the recovery time for patients, the Tuberculosis League closed its hospital in 1955. The organization remained active, however, by dispatching mobile X-ray units into neighborhoods where the disease persisted and continuing to test students in schools. The Tuberculosis League also treated other respiratory ailments, such as asthma, bronchitis, and black lung.

Known today as Breathe Pennsylvania, the organization has gone through several name changes in recent decades, spending time as the Christmas Seal League of Southwestern Pennsylvania, American Lung Association of Western Pennsylvania, and the American Respiratory Alliance of Western Pennsylvania. Breathe Pennsylvania continues to offer lung health education and direct services to residents across southwestern Pennsylvania.

To learn more about the Breathe Pennsylvania Records, you can view more images and read the collection’s finding aid.

Matthew Strauss is the chief archivist at the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.