As the project archivist for the Italian American Program at the Heinz History Center, I spent the last 10 months organizing, preserving, and providing access to collections that document Italian American experiences in Western Pennsylvania, including the Joseph D’Andrea Papers and Photographs (MSS #1113), which can be found in the Detre Library & Archives.

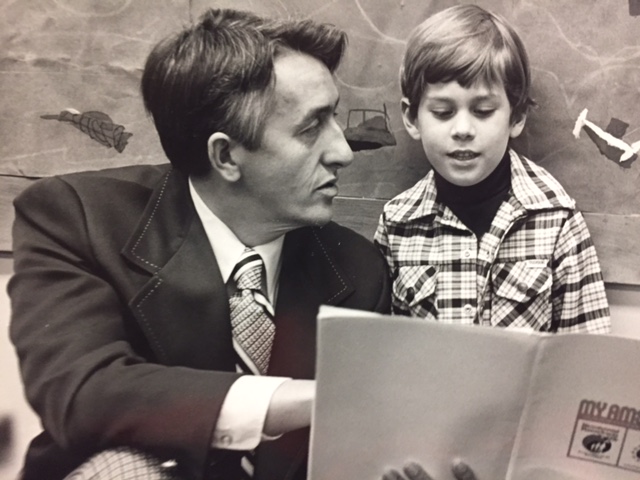

Mr. D’Andrea, a teacher, organizer, and former vice consul of the Italian Consulate, was an instrumental force in the formation of the History Center’s Italian American Program. He immigrated to the United States from Italy in 1947, after World War II, to reunite with his father, who was living in the Pittsburgh area. This collection includes personal records and photographs; documents from the Italian Consulate; beneficial society ledgers; event programs and videos capturing local events in the 1980s and 1990s; along with other records of Italian American activities in Pittsburgh and surrounding areas.

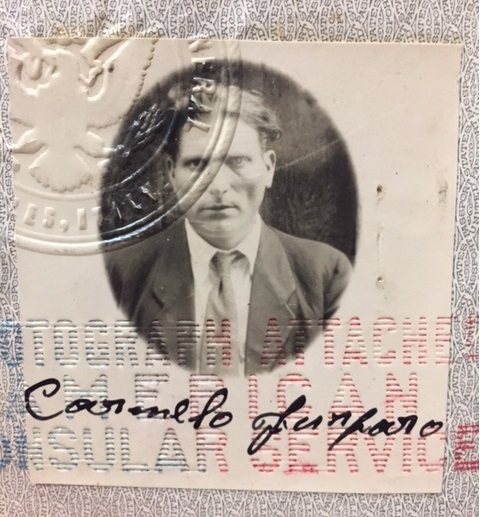

One of the aspects of this collection that grabbed my attention is the visually striking documents it contains, such as marriage licenses, ornate military documents, scrapbooks, and newspaper clippings. Within this large assortment of papers and forms, many human faces appear, making eye contact with the viewer from their loosely pasted frames inside passports and travel documents. These small portraits moved me and piqued my curiosity, prompting me to take a closer look at the history of photo identification.

We’re all familiar with photo identification and the frontal gaze of official portraits—so familiar we don’t think about them beyond wishing we’d smiled or done our hair differently that day. They are the mundane, but necessary, contents of our wallets. Looking at these photos gives a human face to the immigration process, allowing us to see people amidst big life changes. Photo IDs are now synonymous with citizenship and nationality, but that hasn’t always been the case.

The word passport derives from the 15th century Old French compound of passer – to go through – and port – a seaport or door. Passports have been around in various forms since the days of the Old Testament where travel letters from the king are mentioned in the Book of Nehemiah: “If it pleases the king, may I have letters to the governors of Trans-Euphrates, so that they will provide me safe-conduct…”

Fast-forward to the late Middle Ages, in a 1414 Act of Parliament, Henry V of England is credited with creating the first legal passport; a document allowing subjects to travel safely abroad by carrying proof of identity and allegiance. Prior to photography, people were identified based on the word of another person, by symbols, seals, and one’s own testament. Travel was a necessity for some, but most people didn’t stray from their towns and villages.

In 1839, photography was invented by Joseph Niépce, and within a couple of decades it transformed culture in unprecedented ways. Portraiture shifted from upper class luxury to middle class commodity and staple. It was also readily adopted by government and law enforcement agencies. Photography is a compelling form because it is both artistic and technological. It manipulates reality, yet shows the world in a somewhat objective manner. It blends illusion and realism, and is a tool used by artists, journalists, and bureaucrats alike.

In the 19th century, records were being created more than ever as new nation states formed and technologies developed apace. Italy became a nation in 1861, but most people continued to identify with the towns and regions they inhabited, not their newly formed country. However, national identities did take hold, particularly during wartime. Photo identification became useful as borders were created and transportation made movement around the world faster. Not only did photography offer a new way for people to see themselves in the world, it also provided governments with a new way to claim and manage citizens.

Today, we carry numerous forms of photo identification with us. But before World War I, passport laws were lax and not many countries had them. During the war, passports were increasingly used in Europe for security reasons and then to keep skilled workers from emigrating. Also, passports and government forms began to take on some of the characteristics of currency, making them harder to forge and giving them symbolic weight.

But in the 1920s, when the League of Nations created standardized passport laws, many people were offended by whole concept, particularly middle and upper class people, who saw passports and the accompanying descriptive metadata of one’s physical features as an invasion of privacy, as well as an alignment with lower classes and criminals. However, a few years later, it became common practice to require photo identification for all manner of activities.

The history of photo documentation aligns with the development of modern governments and nations, shaping how we identify ourselves within our communities. For many, the quest for an American ID was, and still is, a rite of passage that offers real and symbolic rewards.

There is much more to be said on this subject, and much more to explore within the D’Andrea Papers and Photographs. This collection provides valuable context to our Italian American Program artifacts and gives a human face to the Italian American community in Pittsburgh.

Cate Peebles was the project archivist for the Italian American Program. In summer 2017, she began work as a 2017-2018 National Digital Stewardship Resident at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Conn.