After arriving in Pittsburgh in 1951, Rev. LeRoy Patrick dove headfirst into the fight to integrate the city’s public swimming pools. Though Blacks were not prevented by law from using any city pool, a culture of de facto segregation, enforced by intimidation and outright violence by whites, prohibited them from using certain locations. In Pittsburgh’s East End, instead of being able to swim at the well-kept Highland Park Pool, Black residents were relegated to using the dilapidated Kline Pool on Washington Boulevard.

Along with the Urban League of Pittsburgh Executive Director Alexander “Joe” Allen, Patrick organized a visit by Black youths to the Highland Park Pool. The men gave advance notice to the mayor’s office, asking for police protection to prevent physical violence (an attempt to desegregate the pool a few years earlier nearly resulted in an assault on the protesters). When Patrick led his group into the pool, the white swimmers immediately left the waters and began berating the visitors with threats and epithets. After an hour, satisfied that a statement had been made, Patrick and his group retired to a nearby picnic grove without further incident.

Patrick had just relocated to Pittsburgh from the Philadelphia area to become pastor of the Bethesda United Presbyterian Church in Homewood. A graduate of Lincoln University, Patrick held two master’s degrees (in divinity and sacred theology) from the Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He also studied at Crozer Theological Seminary, from which Martin Luther King Jr. would graduate in 1951. Like King, Patrick believed his role as pastor required activism beyond the walls of the church. (1)

Segregation did not end with this demonstration at the Highland Park Pool. The following year, Patrick returned to the pool with Black youths for 25 consecutive days. Patrick also organized visits to the Paulson Pool in the Lincoln-Lemington neighborhood, where the Black swimmers were pelted with so many rocks by a white crowd that the water had to be drained to remove the projectiles. Patrick reflected on this experience thirty-five years later in an article titled “Dealing with Apartheid, Pittsburgh Style, at the Highland Park Pool in 1950s” written for the Urban League of Pittsburgh, a document that is now part of the LeRoy Patrick Papers in the Detre Library & Archives. Patrick’s first-hand account of these harrowing events is especially valuable considering that major news outlets at the time (other than the Pittsburgh Courier) didn’t cover the protests. City pools would finally become integrated following a successful lawsuit brought against the city that summer by Wendell Freeman and other Black attorneys. (2) Black lifeguards hired by the city (such as the Urban League’s Alexander J. Allen) helped ensure that integration occurred without further violence in the years that followed.

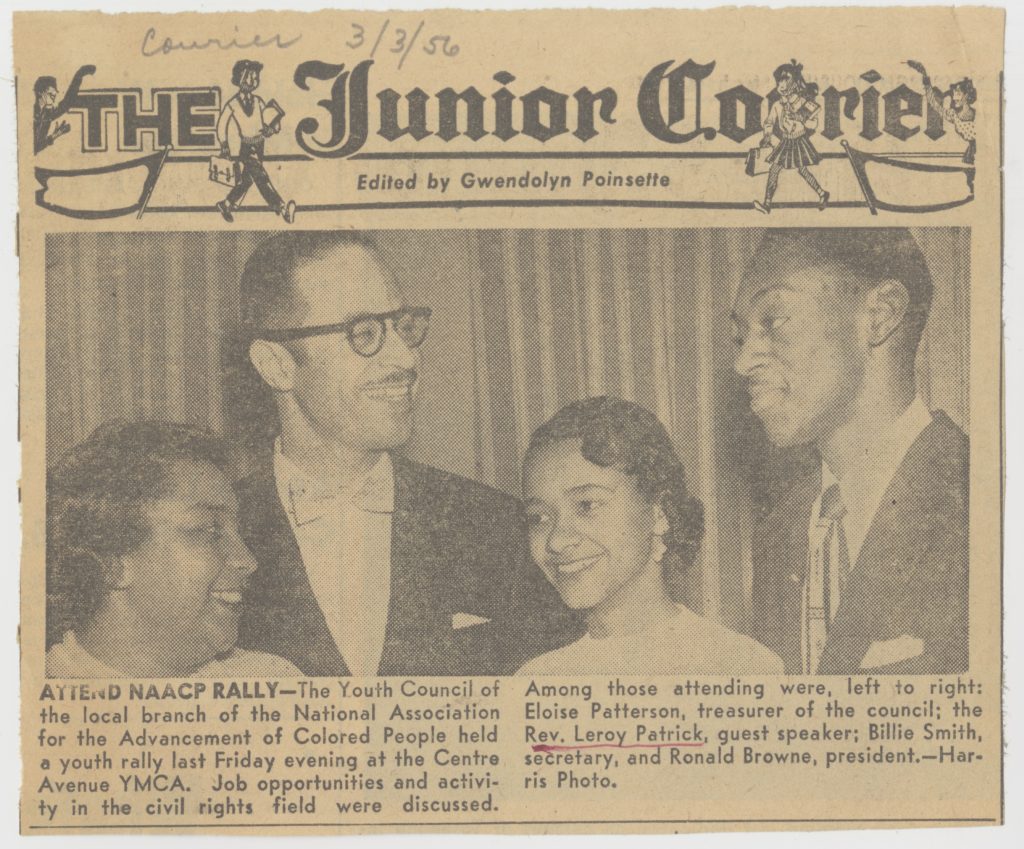

A prescient selection by Time magazine for their 100 “Leaders of Tomorrow” in 1953, Patrick spent the rest of his career advocating for equal opportunities for Blacks in education, employment, and housing. As chairmen of the Pittsburgh NAACP’s Public Accommodations Committee, Patrick organized visits to restaurants and bowling alleys where Blacks were denied service. In the 1960s, working with the NAACP’s United Negro Protest Committee, Patrick was arrested at a construction site where he was protesting unfair hiring practices. Patrick’s activism on the frontlines of the civil rights movement led to hate mail and threats against his life. For a time, he drove with a tire iron in the front seat of his car for warding off any would-be attackers. (3)

In the mid-1960s, Patrick argued that the Pittsburgh Public School Board’s plan to bus 130 Black students from the Lemington School to other schools was “too little and too late.” In a press release that is among his papers at the History Center, Patrick called for the board to commit to complete integration of every school in Pittsburgh, noting that the city’s Black students were receiving “inherently unequal” education, 11 years after the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education case. Patrick later joined the Pittsburgh School board and eventually served as its president.

In his later years, Patrick served as pastor emeritus of his church, board member of the Pittsburgh NAACP, and commissioner of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Comprised of press clippings, correspondence, awards, and photographs, the LeRoy Patrick Papers are a testament to the civil rights leader’s work to build a more equitable city of all Pittsburghers.

Footnotes

1- Torchbearers: The Story of Pittsburgh’s Freedom Fighters, produced by Chris Moore and

Minette Seate (2006; Pittsburgh: WQED), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOJ86JyT-_E

2- Joe W. Trotter and Jared N. Day, Race and Renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh since World War II (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010), 88-89.

3- Ervin Dyer “’Bona fide hero’ of city’s civil rights movement,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 13, 2006. E-5