The following was first published in the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle.

While browsing the website of a local bookstore this summer, I found a horrifying and frustrating book published in 1987 by Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. It’s called “Every Day Remembrance Day,” and it takes the form of a calendar. For each day of the year, Wiesenthal lists instances of deadly antisemitism, from a Vatican-sponsored libel in 1017 to a synagogue bombing in Copenhagen in 1985.

I bought the book. When it arrived, I instinctively and irrationally flipped to October 27. I knew, of course, that the attack in Pittsburgh would not be included among the pages of a book published 30 years earlier. But I suppose I wondered if the day held any omens, and therefore I was stunned to read the following account from October 27, 1905: “A pogrom occurs in Semenovka, Russia. Looting and burning of Jewish property accompanies the slaughter of the Jews—11 are massacred, 11 are gravely wounded.”

The same day, the same toll, separated by 113 years and by the wide ocean between the cruel Old World and the promise of North America. What did it mean?

It meant nothing. A lack of footnotes makes it difficult to determine the source for any particular fact in the book. But further research complicated the coincidence. Yad Vashem notes several Semenovka pogroms, with imprecise dates and conflicting tolls. How heartbreaking it would be if, 113 years from now, no one could agree upon the most basic details of the antisemitic attack that so upended life in our city on October 27, 2018.

In his introduction, Wiesenthal claims that the book is “intended to help prevent the millions of victims disappearing into the abstraction of statistics and at least partially to give them back their true status. If one young reader pauses to think about the fates of these people hidden behind the statistics, then the purpose of this book will have been at least partly fulfilled.” The book certainly prompted me to consider the people behind the statistics—and not just the dead, but also the communities they left behind. But it does little to assist that effort. By limiting itself to dates, cities, circumstances, and tolls, it turns away from actual people and focuses exclusively on the atrocities against them.

In some ways, that’s inevitable. The documentation of these massacres is often limited—and worse, what little survives was sometimes created by the perpetrators. We have only what we have, and we can tell only the stories those documents allow us to tell.

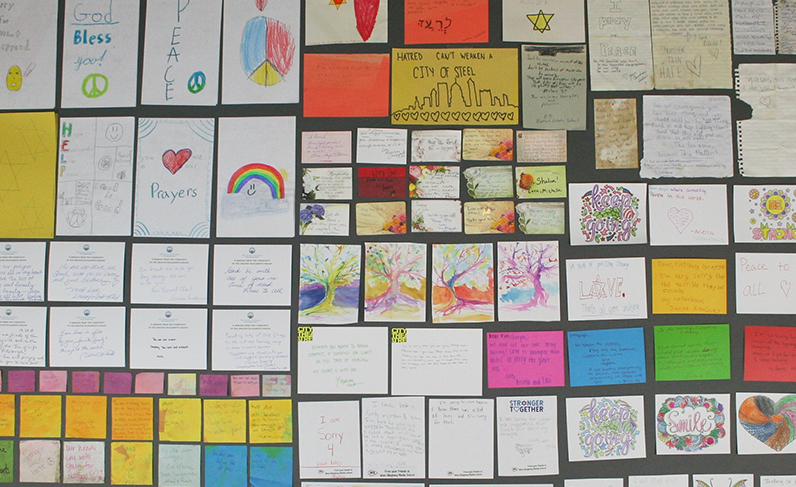

(Above) In the past year, the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives at the Heinz History Center has collected thousands of letters written to individuals and organizations within the local Jewish community following the attack at the Tree of Life synagogue on Oct. 27, 2018. Some were sent directly to various organizations, while others were left at an impromptu memorial outside of the synagogue. Image courtesy of Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.

But we now live at a time of widespread literacy and recording devices in every pocket. We live in a democratic society primed to care about the inner lives of people who hold no particular power or influence. The idea that people would document their individual experiences in the wake of a tragic nearby attack seems natural today. And yet, many won’t. They won’t because it is too painful, which is understandable. Or, they won’t because they assume no one will care what they have to say, which is incorrect.

If you would want to know more about those who died and lived in Semenovka after the October 27, 1905 pogrom, then you can safely assume that someone in the future will want to know more about you—about your thoughts and feelings since October 27, 2018, and also before it. And that goes for any of the world-changing events piling up this exhausting year. Your impressions matter. Your common experiences will become remarkable as time passes. They will define the tone and texture of our times. I encourage you to document your experience and send it to the archive for preservation.

Bearing the weight of world history can seem overwhelming, but it needn’t be. It is not an obligation. It’s an opportunity. While everyone should be aware of the risks involved in mining earlier traumas, many people find that the act of documenting their experiences can bring a sense of empowerment and purpose during uncertain times.

And although it might initially feel uncomfortable to articulate your pain when others seem to have been hurt so much worse, documentation is not an inherently self-centered act. Done right, it can be almost selfless. You will be helping someone in the future find meaning in their hour of confusion, and you are asking for nothing in return.

Eric Lidji is the director of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives.