The following post originally appeared in the summer 2015 issue of Western Pennsylvania History Magazine.

In the late 1930s, when Jacob A. Evanson joined the staff of the Pittsburgh Board of Education as special supervisor of vocal instruction, folklorists and musicologists were scouring America in search of old songs before they disappeared. The recording expeditions of father-and-son duo John and Alan Lomax, conducted under the banner of the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, inspired folklorists across the country to join in the effort to collect and preserve America’s folk traditions.

The Jacob A. Evanson Papers attest to the excitement these developments generated among researchers, musicians, and the public. Included in the collection are hundreds of songs Evanson collected and transcribed from books, periodicals, oral sources, and audio recordings from various repositories, including the Archive of American Folk Song (now the Archive of Folk Culture). Nearly all of the songs include musical notation in addition to lyrics, while Evanson’s annotations and notes provide contextual information regarding song origins and themes.

Evanson, who taught music education at Case Western Reserve University for over a decade before moving to Pittsburgh, wanted to do more than collect Pittsburgh’s folk songs: He wanted to integrate them into Pittsburgh Public Schools’ musical curriculum. Until 1940, the music department was directed by Will Earhart, a nationally respected educator who championed a curriculum that aimed to foster in his students a lifelong appreciation for classical music. While Evanson acknowledged the importance of classical European music, he felt the curriculum should include a regional element to supplement and to contrast the works of other cultures. Regional folk songs — “songs that state the life immediately about them, or of some phase of the past of that life” — would better reflect the students’ own experiences and interests.[i]

Evanson encouraged music teachers to act as “song catchers” in and out of the classroom — to record the music they heard at lunch and recess, at bus stops, and on city streets. By September 1946, nearly 80 songs had been compiled and distributed to every public school in the city. This development caught the attention of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which featured an article that month highlighting the emergent integration of folk songs into the musical curriculum of Pittsburgh Public Schools under Evanson’s supervision, calling it a “revolution.”[ii] Songs included “General Braddock,” “At the Forks of the Ohio,” “Johnstown Flood,” and “Pittsburgh is a Great Old Town” — the last of which, according to Pete Seeger, was first conceived by Woody Guthrie in 1941 and later adapted by Alan Lomax for a radio broadcast.[iii]

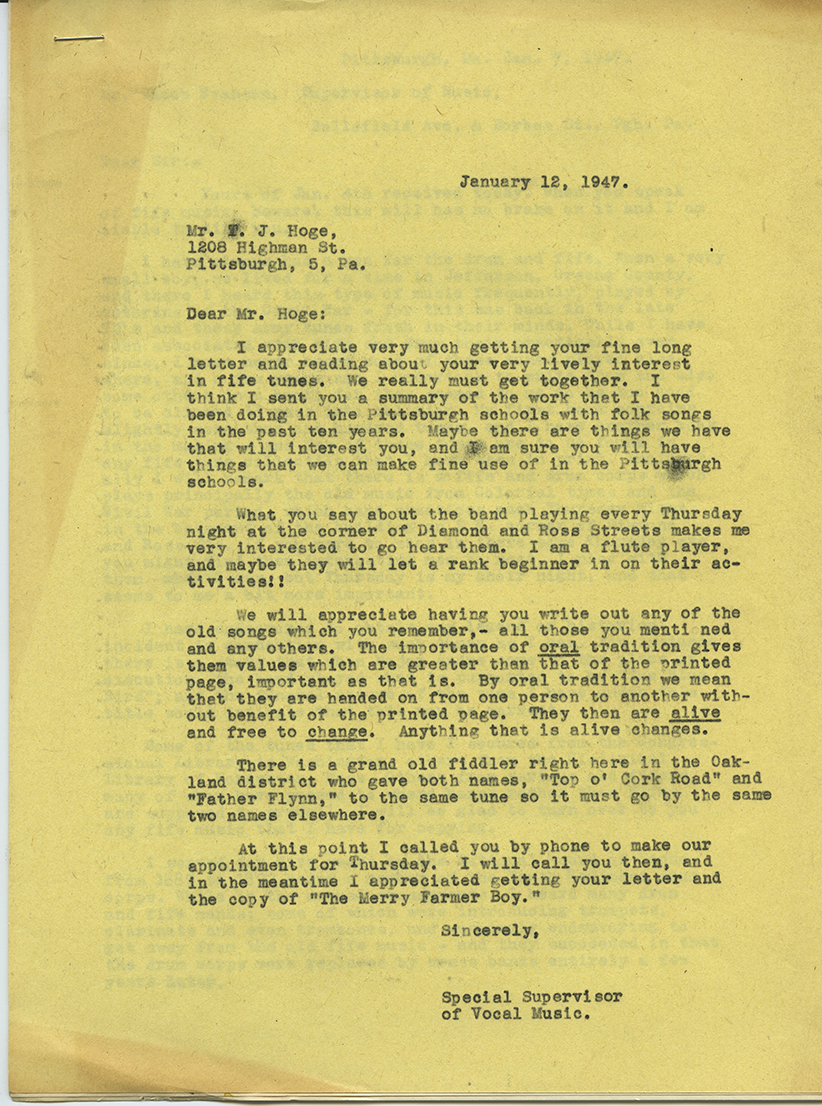

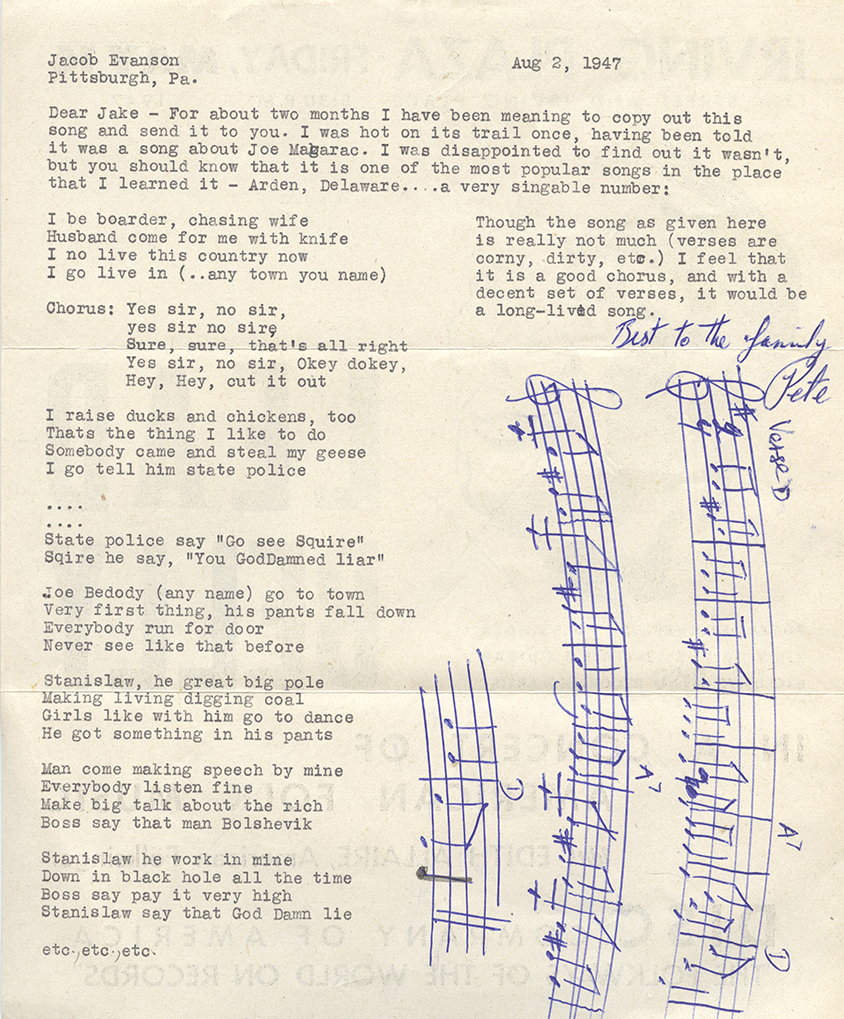

Following this exposure, Evanson decided to expand his collecting project by enlisting the help of the public through subsequent articles and notices encouraging readers to contribute to the collection. For more than a year, he regularly received contributions from interested readers with songs to share — songs they remembered from their youth, heard from a friend, and even songs they composed themselves. These contributions were supplemented by Evanson’s fieldwork, which consisted of house call to Pittsburgh residents who recited songs that had been passed down from previous generations. The songs Evanson compiled were performed before public audiences by student choirs throughout his tenure as supervisor until his retirement in the mid-1960s.

Evanson presented his research and compilations at folklore conferences and in several publications, and in 1959 he supplied the liner notes to Vivien Richman Sings Folk Songs of West Pennsylvania, an album issued by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Such a recording could not have been made without the efforts of Evanson and his many song catchers, whose trove of songs comprises the bulk of the Jacob A. Evanson Papers, available for research at the Detre Library & Archives.

[i] Jacob Evanson to J.S. Duss, November 29, 1946. Jacob A. Evanson Papers, Detre Library & Archives, Sen. John Heinz History Center.

[ii] “‘Revolution in Pittsburgh’ And That’s No Musical Joke, Son,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 17, 1946.

[iii] Jacob A. Evanson, “Folksongs of an Industrial City,” Pennsylvania Songs and Legends (Philadelphia: University of PennsylvaniaPress, 1949), 440-441.

Nicholas Hartley is a former Heinz History Center project archivist.