“Preliminary advices indicate that within the next 24 hours, the Chiefs of State of the Principled Allied Powers will proclaim the Day of Victory in Europe and the end of organized European hostilities.”

How did Carnegie-Illinois Steel Company, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel, prepare for the end of World War II? Its plants at Duquesne and Homestead were dynamic sites of wartime steel production, with federal dollars coming in the form of government contracts and building projects financed by the New Deal’s Defense Plant Corporation (DPC). Steelworkers served and died on the battlegrounds of Europe and the Pacific. As the History Center’s popular We Can Do It! WWII exhibition last year showed, Pittsburgh was a hotbed of wartime industrial activity.

Planning for the war’s end did not just encompass the dwindling of government contracts or the changes in a plant’s labor needs. The management of Carnegie-Illinois also had to determine how to break the news to its steelworkers and how to honor the occasion of the end of the war. As early as Aug. 28, 1944, the Production Planning Department at Duquesne Works was putting plans in place for what they called “X-Day,” or the date that the level of wartime production would drop below the rate of normal operations. Early indications were that X-Day could coincide with V-Day or VE Day, thus leading the Carnegie-Illinois planners to worry about the “sudden emotional effect” of the news of war’s end:

“Steps should be taken by the Steel Industry, and probably all Industry, with the O.W.I. [Office of War Information] and other Federal Agencies to control news broadcasts to develop a tapering off of the public emotional state so that the final announcement of a complete end of European hostilities will not have a sudden explosive emotional effect.” –E.C. Oberg, manager of operations, Pittsburgh District, Aug. 28, 1944

An updated Dec. 30, 1944 plan for X-Day noted that “X-day plans are not to be considered as automatically following V-E Day.”

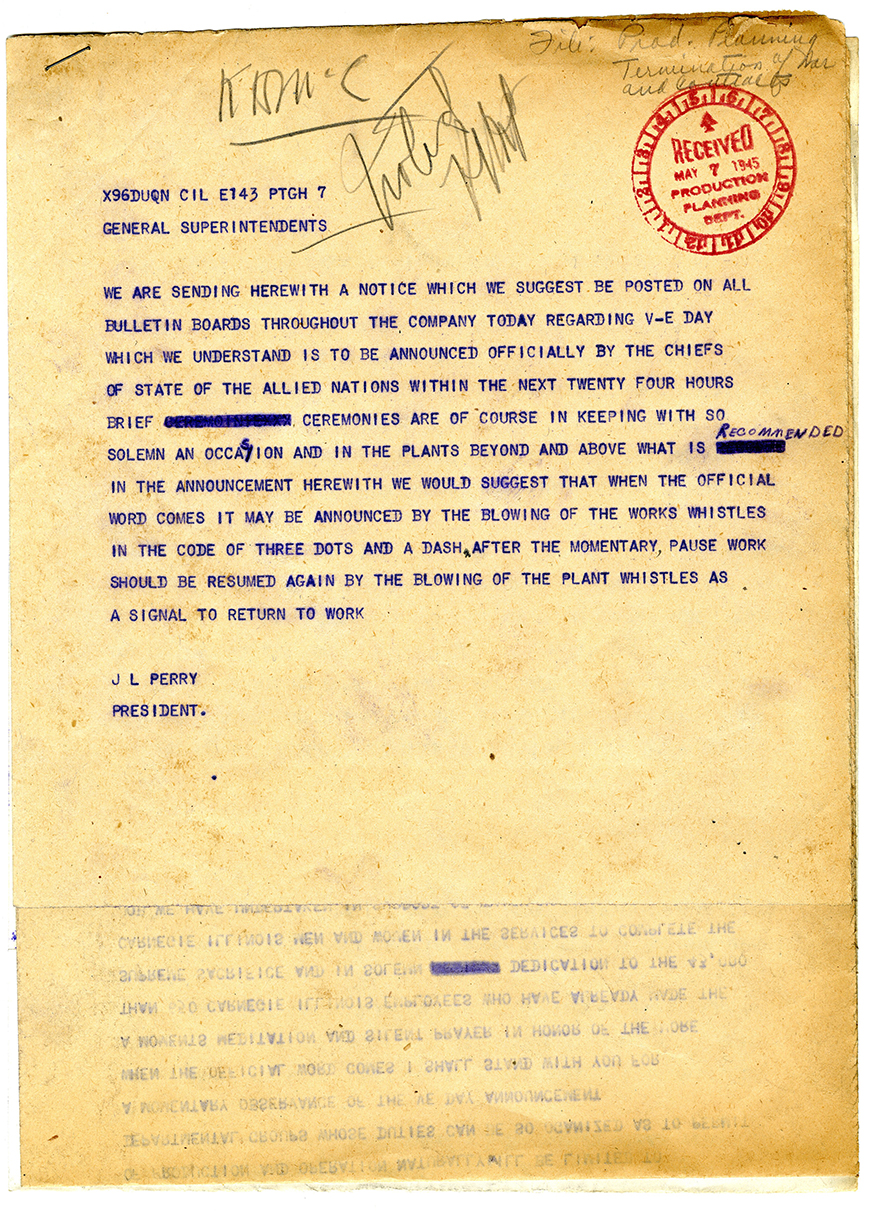

On May 7, 1945 – the day before VE Day – John Lester Perry, president of Carnegie-Illinois, sent an internal telegram to the general superintendents of the various plants under his supervision. The message reads, in part:

“We are sending herewith a notice which we suggest be posted on all bulletin boards throughout the company today regarding V-E Day which we understand is to be announced officially by the Chiefs of State of the Allied Nations within the next twenty four hours…Herewith we would suggest that when the official word comes it may be announced by the blowing of the works whistles in the code of three dots and a dash[.] After the momentary pause work should be resumed again by the blowing of the plant whistles as a signal to return to work[.]”

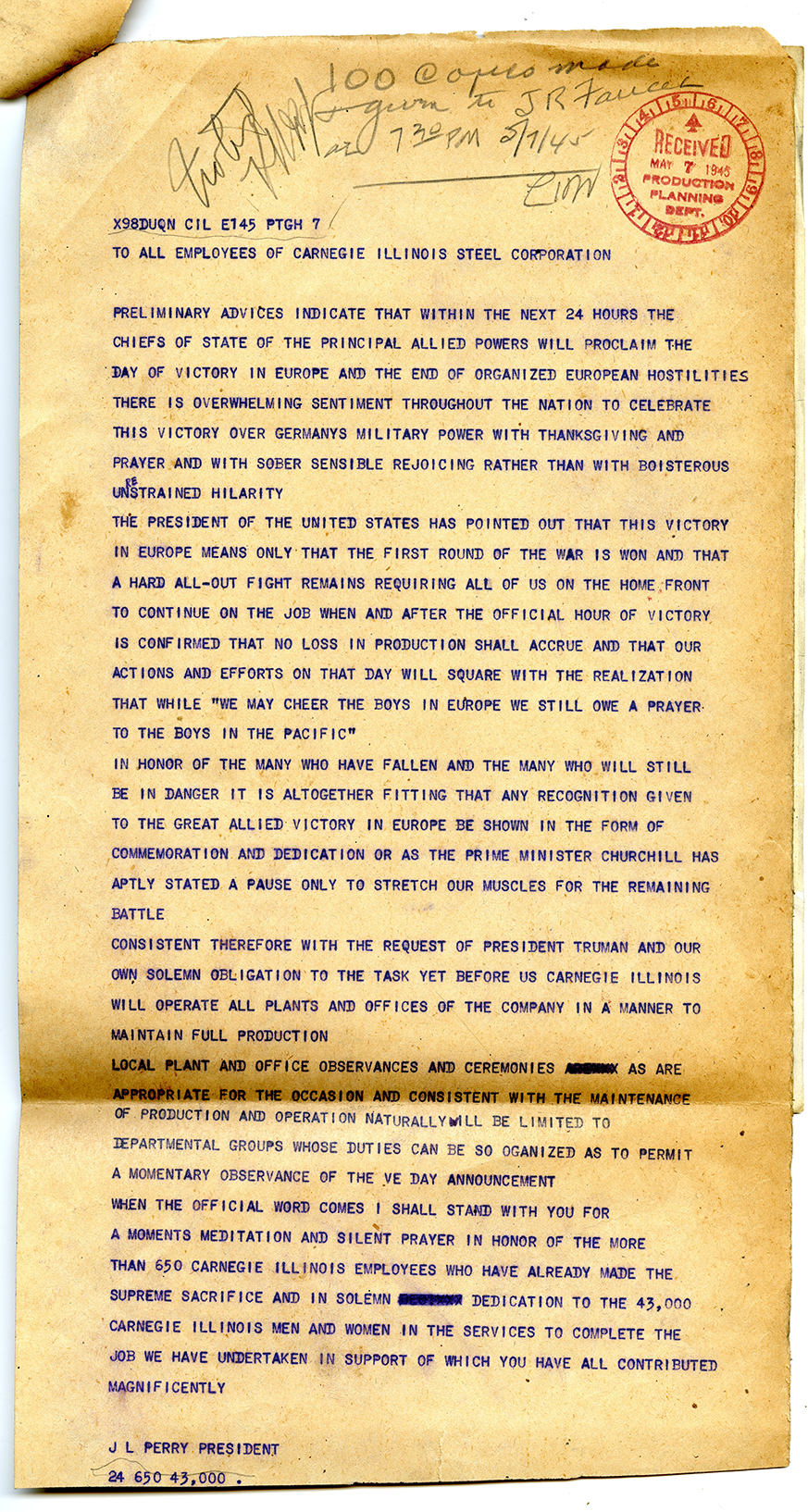

Three dots and a dash – or Morse code for “V” (as in “Victory”) – would be proclaimed across Carnegie-Illinois plants to mark the end of the war in Europe. It would not be a time for unrestricted celebration at these plants, however. According to the official statement by Perry:

“To All Employees of Carnegie Illinois Steel Corporation … There is overwhelming sentiment throughout the nation to celebrate this victory over Germany’s military power with Thanksgiving and prayer and with sober sensible rejoicing rather than with boisterous unrestrained hilarity[.] The President of the United States has pointed out that this victory in Europe means only that the first round of the war is won and that a hard all-out fight remains, requiring all of us on the home front to continue on the job when and after the official hour of victory is confirmed, that no loss in production shall accrue and that our actions and efforts on that day will square with the realization that while ‘We may cheer the boys in Europe we still owe a prayer to the boys in the Pacific.’”

VE Day was a day for celebration and reflection – and also a working day for Pittsburgh’s steelworkers. The plant whistle at Duquesne Works blew a “V” for “Victory” and then called its workers back to their jobs with another whistle. X-Day came in late August of that year, mere weeks after VJ Day. In the meantime, Duquesne Works and other Carnegie-Illinois plants and U.S. Steel subsidiaries were hard at work contributing to the American effort to win the war. Behind the scenes, management planned for the industrial outcome of that celebratory day, outlining how to handle the cancellation of government contracts and the status of operations at the various Carnegie-Illinois plants. Pittsburgh’s steel industry was impacted greatly by both the beginning and end of World War II.

Administrative records regarding wartime orders, operations, production, and planning reside in the files of Duquesne’s General Superintendent during World War II, King H. McLaurin, as part of the Detre Library & Archives’ Duquesne Steel Works Records (MSS 42). Additions to the collection are currently being processed as a part of the Library & Archives’ National Historic Publications and Records Commission’s (NHPRC) Documenting Democracy grant, which enables staff to preserve and make accessible records relating to Western Pennsylvania’s industrial heritage.

Kate Madison is a NHPRC graduate student intern volunteer with the Detre Library & Archives.