The following post is adapted from a talk given by Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives Director Eric Lidji on May 27, 2018 at the Homewood Cemetery as part of a Memorial Day program.

Soldiers write home about surprisingly common things during wartime.

Consequential events are usually too sensitive to discuss directly—put it in writing and a censor will black it out. What remains are daily occurrences. You see a lot of descriptions of meals, of weather, of promotions, of radio programs and books, of new friends, of leaves taken and pranks witnessed. You see a lot of questions about home. How is everyone? What’s new? A recurring subject is the postal system. Soldiers regularly start letters by listing the date when an earlier letter arrived. They are trying to figure out how long it takes a letter to get to the front and whether any letters might have gone missing along the way.

Objects acquire meaning through their contents and also through their context. The contents are the things you see when you look at an object. You can read these letters for yourself and learn about the wartime routines of soldiers. Context is invisible. It requires outside information about the creation of the object—the setting and circumstances and the backgrounds of key figures. One of the main responsibilities of an archive is to enhance the meaning that can be gleaned from an object by providing context for it.

An extreme example of this principle can be found in the last letters written by solders who were later killed in the line of duty. The grave circumstances of these documents give the words added relevance. Every word in these letters seems to carry the weight of the entire life of the soldier who wrote them. Even the most ordinary observation can become unbearably poignant or ironic when it is forced to stand as a final rumination.

The following vignettes use last letters from the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives to commemorate the lives of four soldiers who were killed in the line of duty.

ALLEN CHAMOVITZ

Chamovitz-Eger Family Papers and Photographs,

Rauh Jewish Archives at the History Center.

Allen Chamovitz grew up in a large family. He was the second of five children, and his many aunts, uncles and cousins accounted for a sizeable portion of the small Jewish community in Aliquippa, Pa. Their names fill the membership list of their local synagogue.

Allen’s father and uncle ran a shoe store. Before every big sale, the children would split into groups and canvas the entire town to hang up flyers. Four of the Chamovitz boys became doctors. Allen was the exception. He had different aptitudes. He went to college, partly to prove that he could, and then went to work for an uncle in the jewelry business.

Allen enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces shortly after America entered the war. He was killed in June 1943, in a midair collision during a training exercise at Alamogordo Air Force Base in New Mexico. His four brothers also entered the service, and so their loss was compounded by their isolation from each other and from their family in Aliquippa.

The only correspondence we have from Allen is a recording made at a party given in his honor on August 7, 1942. It was a Friday night, the night before he reported for duty.

Transcription

Mother, as I’m speaking to you I can almost see you. I suppose it’s only natural for a mother to worry about her son that’s going where I am. Every son about to leave for the Army tries to reassure his mother that he’ll be all right and believe me I know it’s stressful. Just try to remember that I was very happy when I left, and I’m very contented now. I know that I’m new around here and the life here is new to me, but I’m sure I’ll get used to it. I’m leaving you mother, but there are several things I wanted to say to you but hadn’t the courage. And now that I’m not facing you, I think I can. I just want to say that I love you with all my heart and miss you terribly. I’m sorry for the times that I made you feel bad, and I’m proud of the happy moments we had together.

Mother, I’m only your son, but if I may I’d like to give you a little advice. You told me several times that you made a resolution to keep the boys close to you and take them with you wherever you went. Do this, and I’m sure you’ll be very happy. See that I miss you, dad and all the boys with all my heart. Even though they are my own brothers, I am, and I’m sure you are, very proud of them.

I realize that I’m getting sentimental but if I may I’d like to ask you a favor. Every once in a while, if you feel like it, just sing the song “For the sake of society.” Remember you used to sing it when we were boys, and every time I’d hear it used to go into the kitchen because I didn’t want you to see me cry. In close, mother, I’m trying to be a good boy.

Your loving son,

Allen

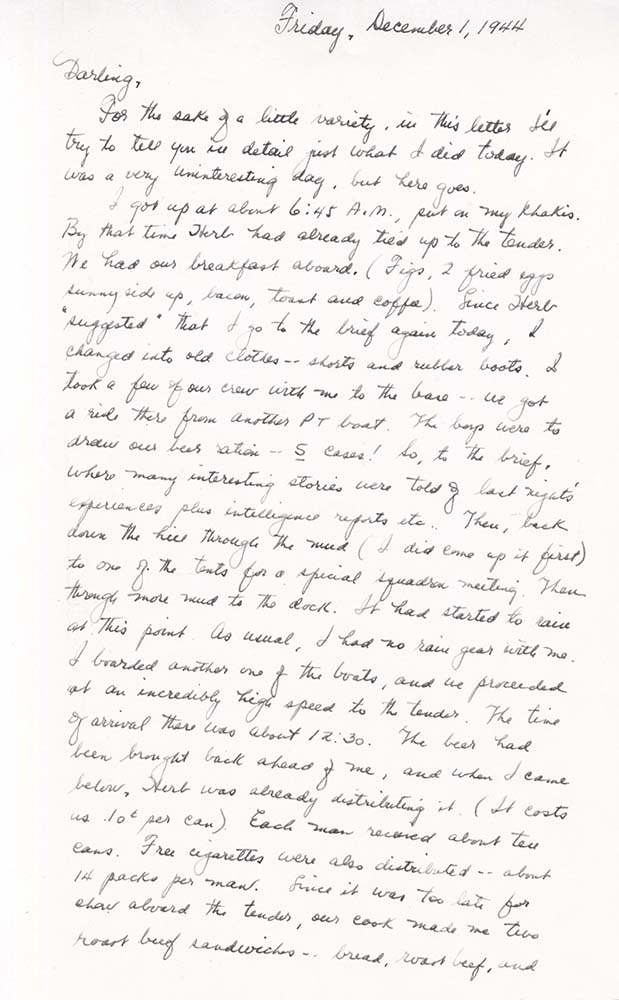

WILLIAM ADELMAN

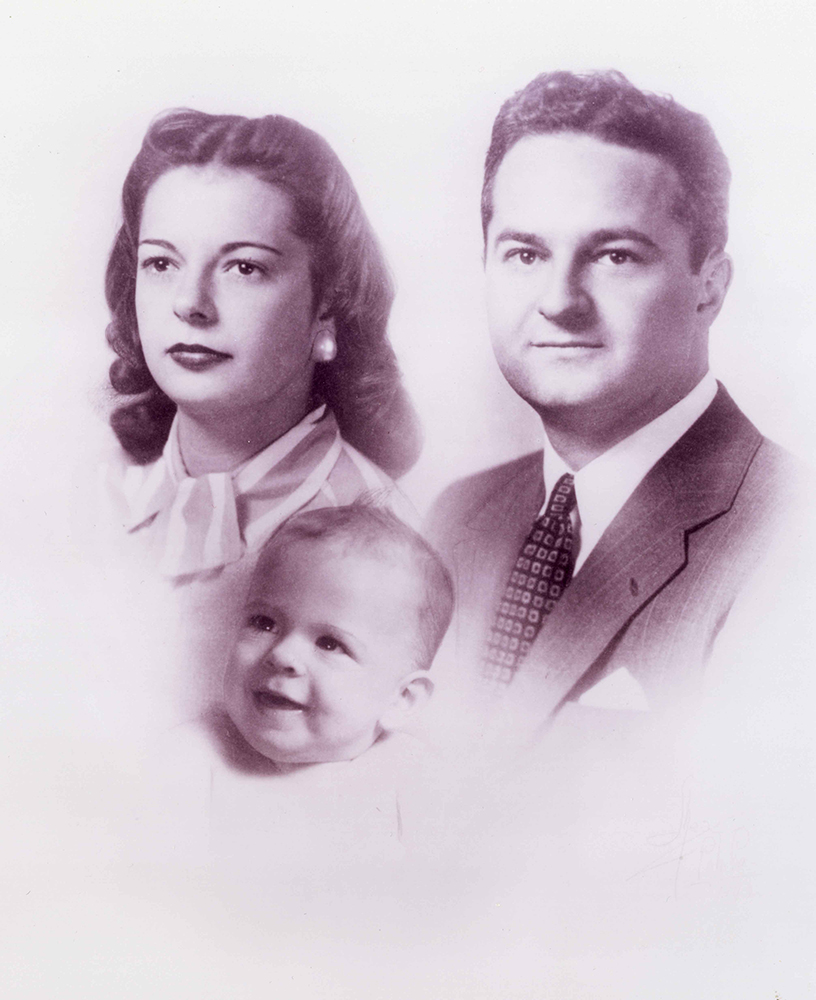

William Ira Adelman led a life of achievement. His family started in the jewelry business and transitioned to the wholesale lumber industry. (For many years, Adelman Lumber Co. was located at 13th and Smallman, which is now the home of the History Center.) William graduated from Shadyside Academy and Harvard University, uncommon accomplishments for a young Jewish man in Pittsburgh in the 1930s. He joined the family lumber business in 1936 and married Meryl June Ruben in 1940. By the time he enlisted in the U.S. Navy in late 1943, he had two children under the age of four.

He was assigned to PT-323, a patrol torpedo boat squadron with the Seventh Fleet in the Pacific theater, and in October 1944 his boat fought in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which some consider to be the largest naval battle in history. During the conflict, he gave the order to attack a Japanese destroyer escort, leading to the destruction of the larger ship.

William’s letters to his wife are confident, even when describing intense situations. In his letters, the Japanese are strong but the Americans are stronger, the war is tough but the soldiers are up to it. The Battle of Leyte Gulf, he wrote, was “beautiful and terrible.”

PT-323 was destroyed by a kamikaze on December 10, 1944, only a few months after the Japanese had introduced the strategy. The captain of PT-323 was killed in the attack and 11 of his men were wounded. William went missing and was declared dead in January.

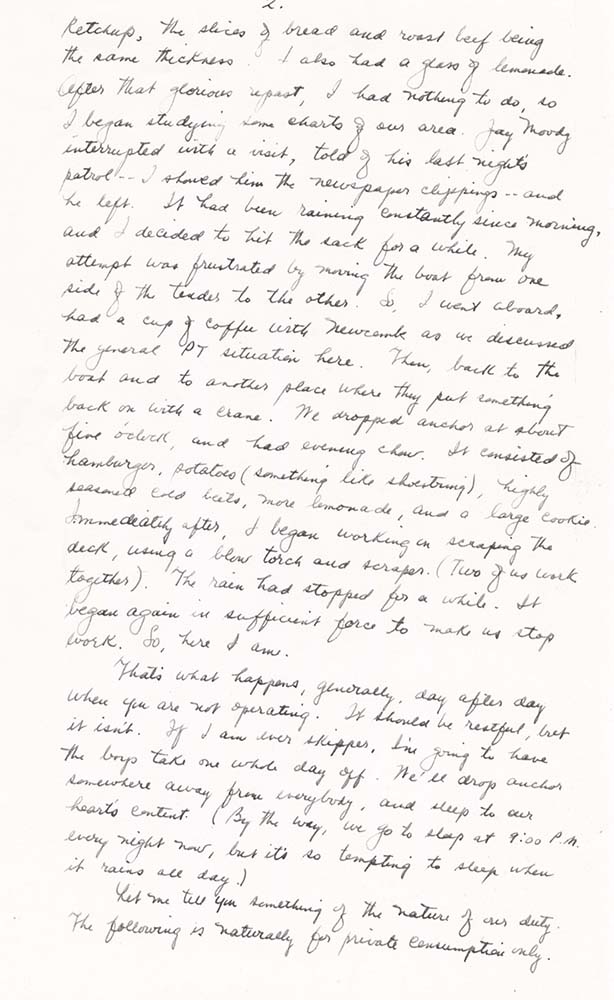

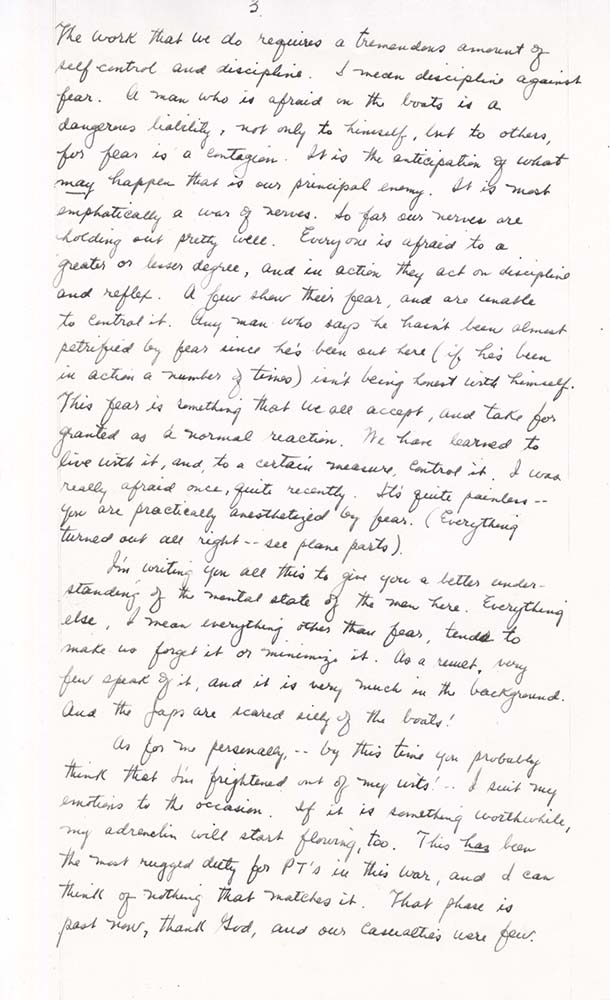

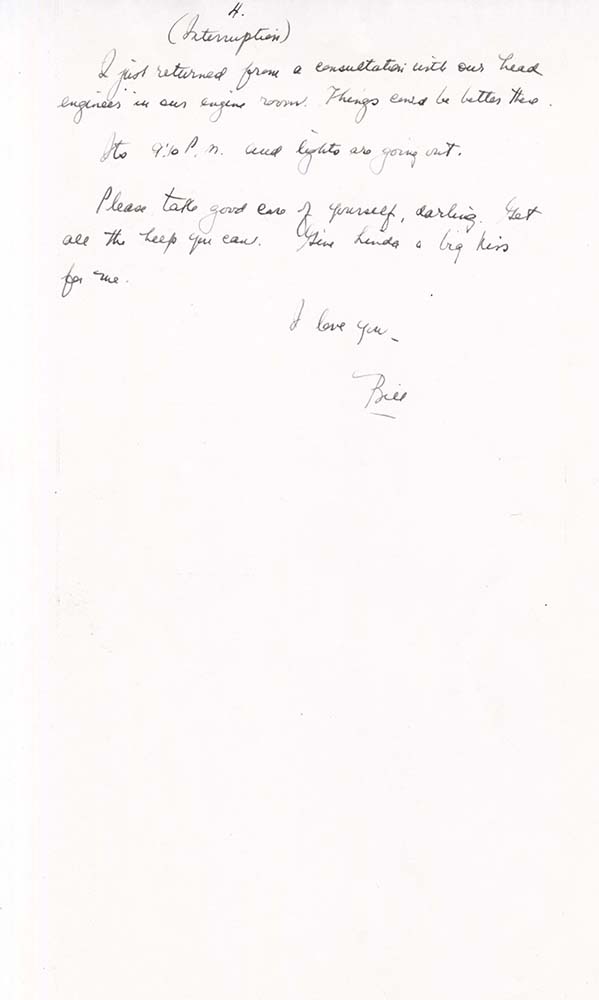

His final letter to his wife is dated December 1, 1944, nine days earlier. After brief comments about his daily routine on the ship, his tone suddenly turned reflective:

…Let me tell you something of the nature of our duty. The following is naturally for private consumption only. The work that we do requires a tremendous amount of self-control and discipline. I mean discipline against fear. A man who is afraid on the boats is a dangerous liability, not only to himself, but to others, for fear is a contagion. It is anticipation of what may happen that is the principal enemy. It is most emphatically a war of nerves. So far our nerves are holding out pretty well. Everyone is afraid to a greater or lesser degree, and in action they act on discipline and reflex. A few show their fear, and are unable to control it. Any man who says he hasn’t been almost petrified by fear since he’s been out here (if he’s been in action a number of time) isn’t being honest with himself. This fear is something that we all accept, and take for granted as a normal reaction. We have learned to live with it, and, to a certain measure, control it. I was really afraid once, quite recently. It’s quite painless—you are practically anesthetized by fear…

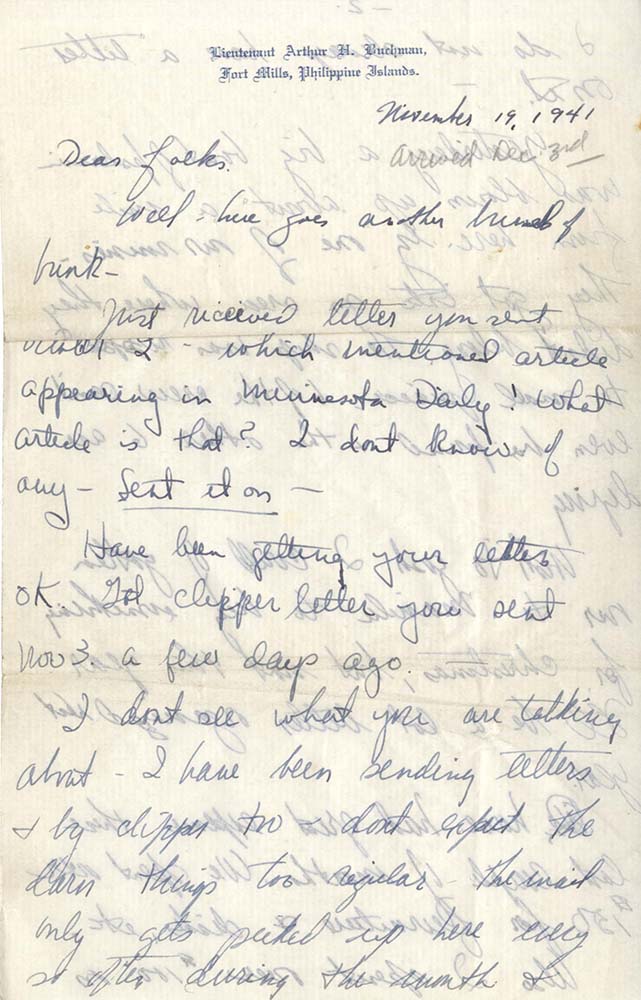

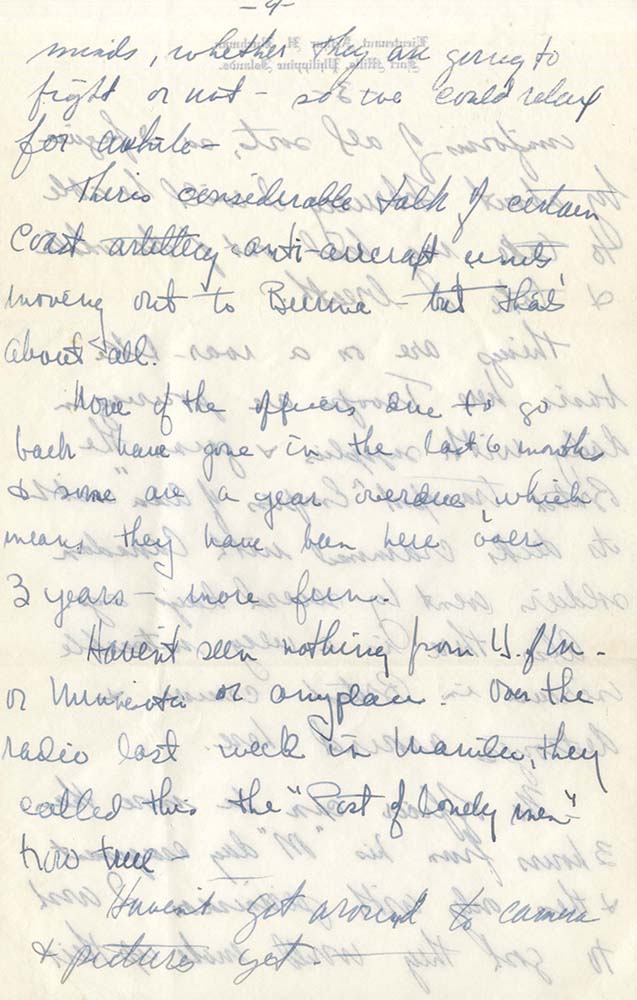

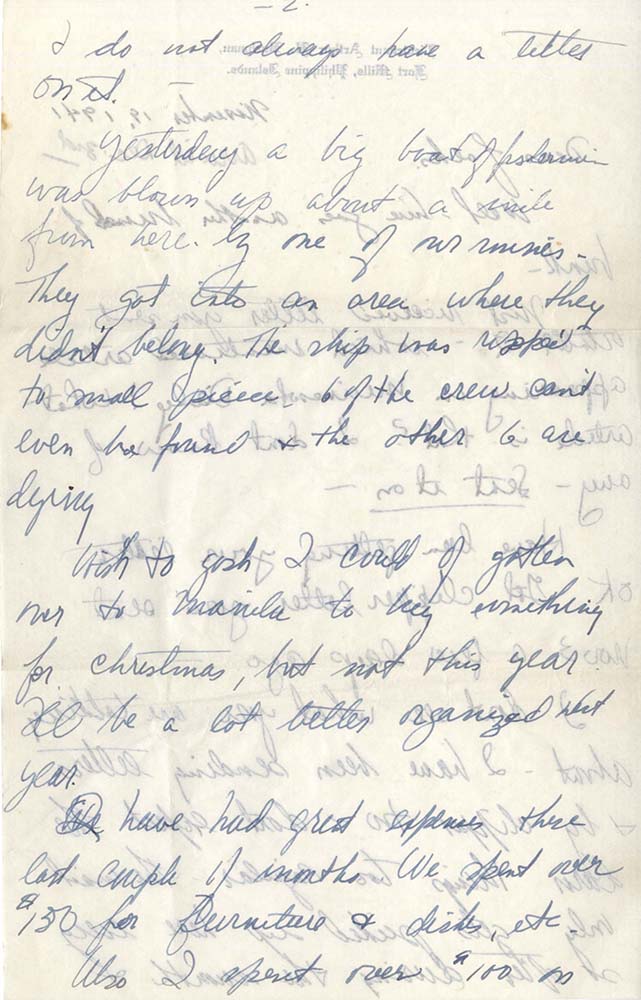

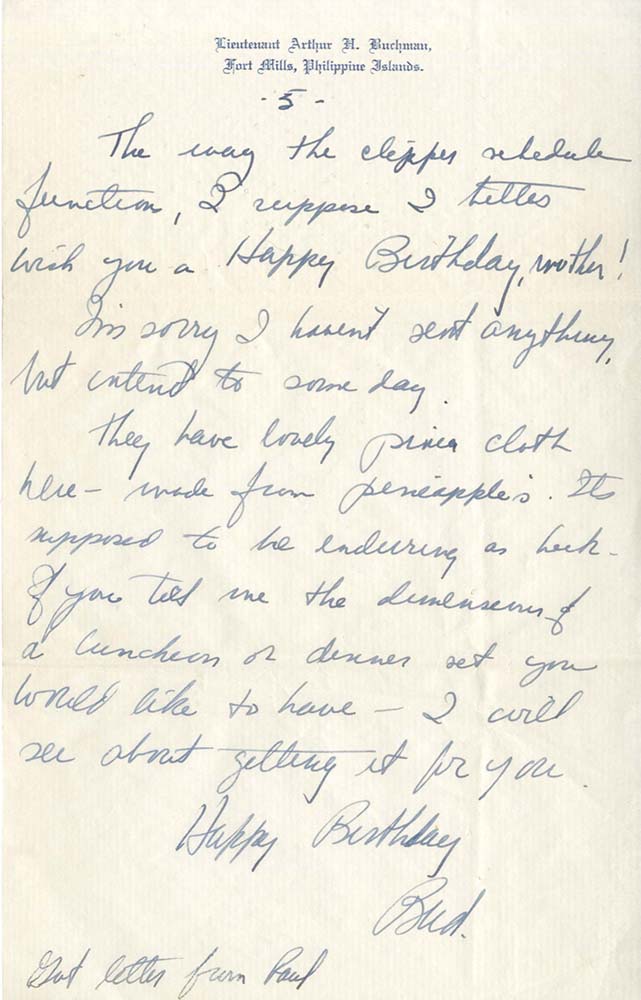

ARTHUR BUCHMAN

Arthur Buchman was attending the University of Minnesota in the late 1930s when his parents relocated to Pittsburgh for work. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in early 1941, soon after graduating. His letters “home” went to Pittsburgh, which had never been his home.

His early letters chronicle a long sea voyage from the west coast to a military base in Manila. His biggest concern was the heat. If the South Pacific was already so hot and humid in the rainy season of October, he wondered, what would it be like in summer? He was sweating through two uniforms daily, and the laundry crew was working overtime.

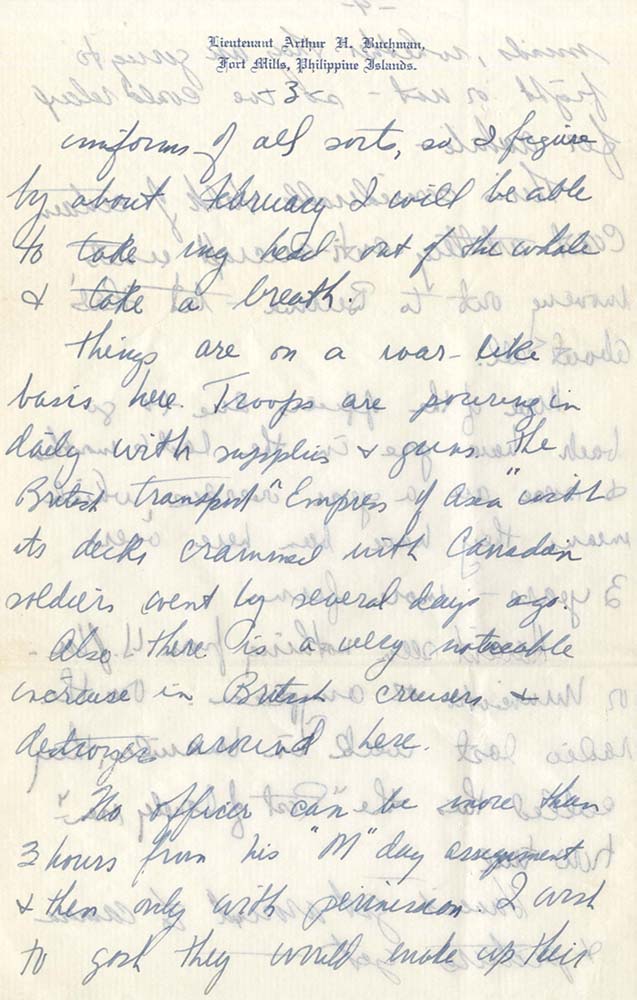

Arthur was one of the American soldiers who served during the two-year window between the start of World War II and the entrance of the United States. He was watching a war being fought by other countries, unsure of whether or when he would become a combatant. Tension infuses his last traditional letter home, dated November 19, 1941.

In it, he wrote:

Things are on a war-like basis here. Troops are pouring in daily with supplies and guns. The British transport “Empress of Asia” with its decks crammed with Canadian soldiers went by several days ago.

Also there is a very noticeable increase in British cruisers and destroyers around here.

No officer can be more than 3 hours from his ‘M’ day assignment and then only with permission. I wish to gosh they would make up their minds, whether they are going to fight or not – so we could relax for awhile.

The uncertainty ended 18 days later, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, throwing Buchman into the war. The mission of those first American troops was to hold the Japanese until more American forces could be mustered. Arthur fought in the Battle of Corregidor in May 1942 and was taken prisoner when the Japanese captured the island.

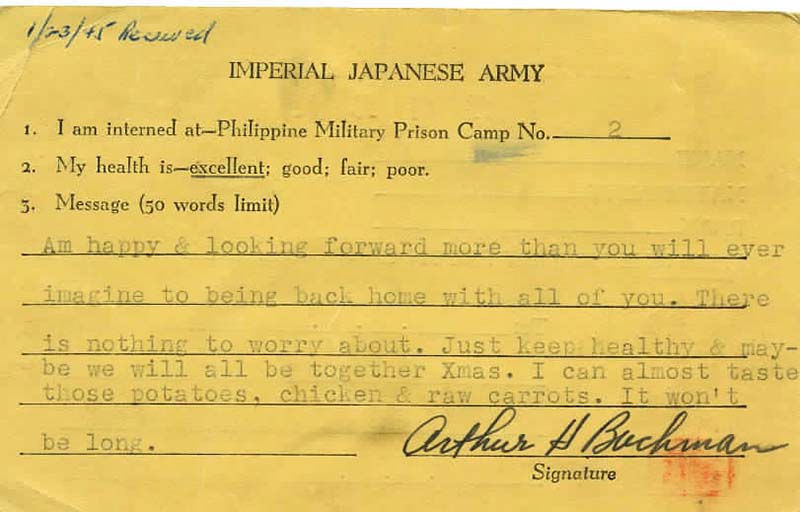

For the next three years, the only messages that the Buchmans received from their son came in the form of prisoner of war cards. Each pocketsize card was pre-printed with information. The prisoner was allowed to underline the word best describing his health: excellent, good, fair, poor. There was also room for a 50-word message to loved ones.

Even though Arthur is unfailingly cheerful in these brief messages home, the cards are cryptic and unsettling. In many cases, he appears to be trying to send coded messages to his family, but the precise meaning of these messages is often difficult to ascertain.

Arthur was killed in December 1944 when Allied troops attacked his unmarked ship. The last POW card arrived in Pittsburgh on January 23, 1945, five weeks after the accident and several months before the Buchmans were officially notified of their son’s death.

See more correspondence from Arthur Buchman on this blog post: Arthur Buchman’s Cards Home.

WILLIAM BARSKY

William Barsky was the fourth of seven children and the first person in his family born in the United States. In early 1926, he experienced three tragedies. His older sister Fannie died of pneumonia, and his mother died of grief the same day. Two months later, his father died from complications during an appendectomy. William was fourteen years old.

After graduating from high school, William moved with two of his brothers out to California. He was living there when the United States entered the war, and he enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was initially stationed in Northern Ireland and England but shipped out to North Africa in February 1943 and had proceeded north to Italy by February 1944. He was stationed in Italy as a radio operator with the 804th Tank Destroyer Battalion when he was killed in April 1945, most likely in a tank explosion outside of Rome.

Between April 1942 and April 1945, William sent a letter at least weekly, and sometimes more frequently, to his older sister Sybil and her husband Joe. Simple affairs fill his correspondences. He discusses meals, friends and family, and he describes his observance of Jewish holidays in unlikely corners of the world. In his letters written in late March and early April 1945, he repeatedly expresses restrained optimism about the state of the war, both in the European and the Pacific theaters. Victory is starting to feel inevitable.

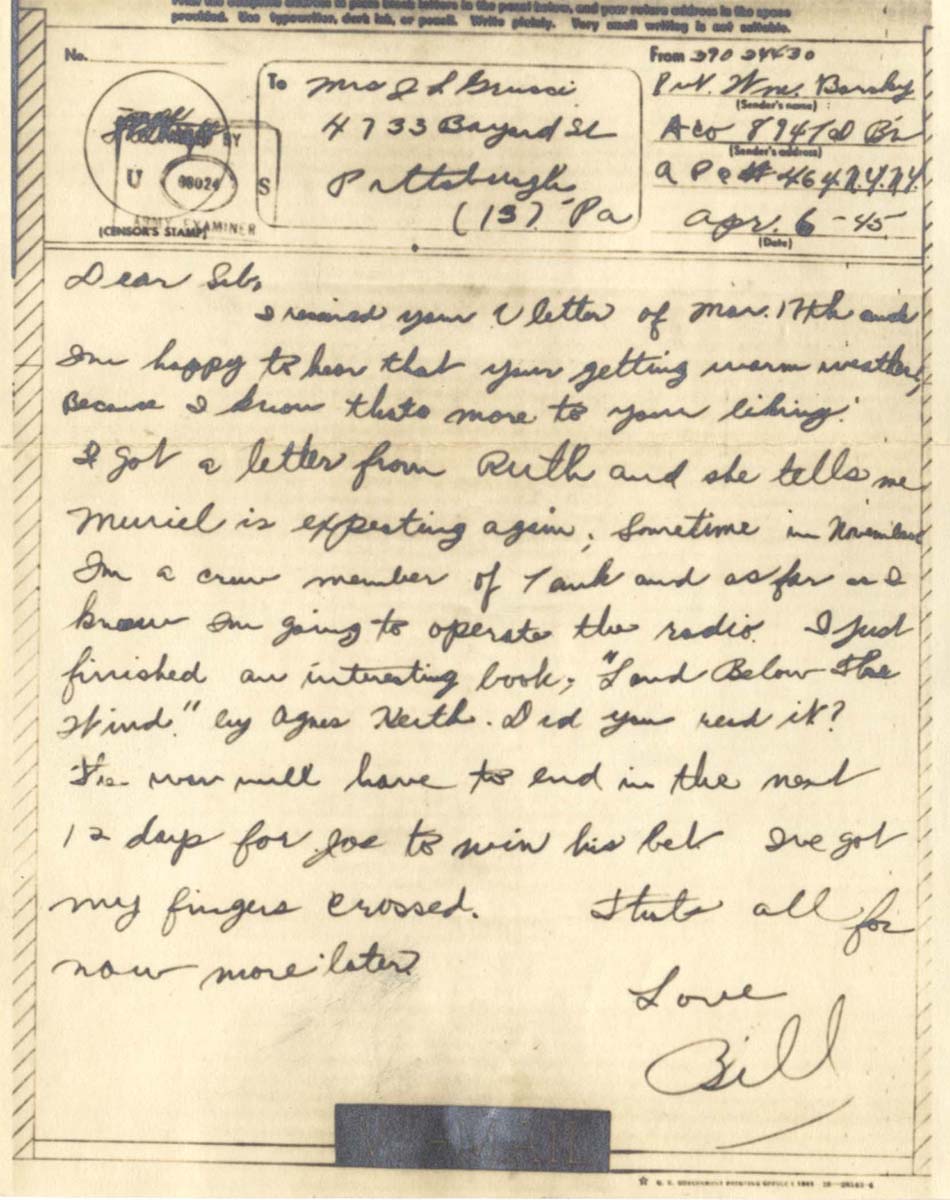

His final letter to his sister, dated April 6, 1945, is brief and ironic.

His final letter to his sister, dated April 6, 1945, is brief and ironic.

Dear Sib,

I received your letter of Mar. 17 and I’m happy to hear that your [sic] getting warm weather, because I know that’s more to your liking.

I got a letter from Ruth and she tells me Muriel is expecting again; sometime in November.

I’m a crew member of [a] tank and as far as I know I’m going to operate the radio. I just finished an interesting book, “Land Below the Wind” by Agnes Keith. Did you read it?

The war will have to end in the next 12 days for Joe to win his bet. I’ve got my fingers crossed. That’s all for now more later.

Love,

Bill

What can these “last letters” tell us about the experience of war?

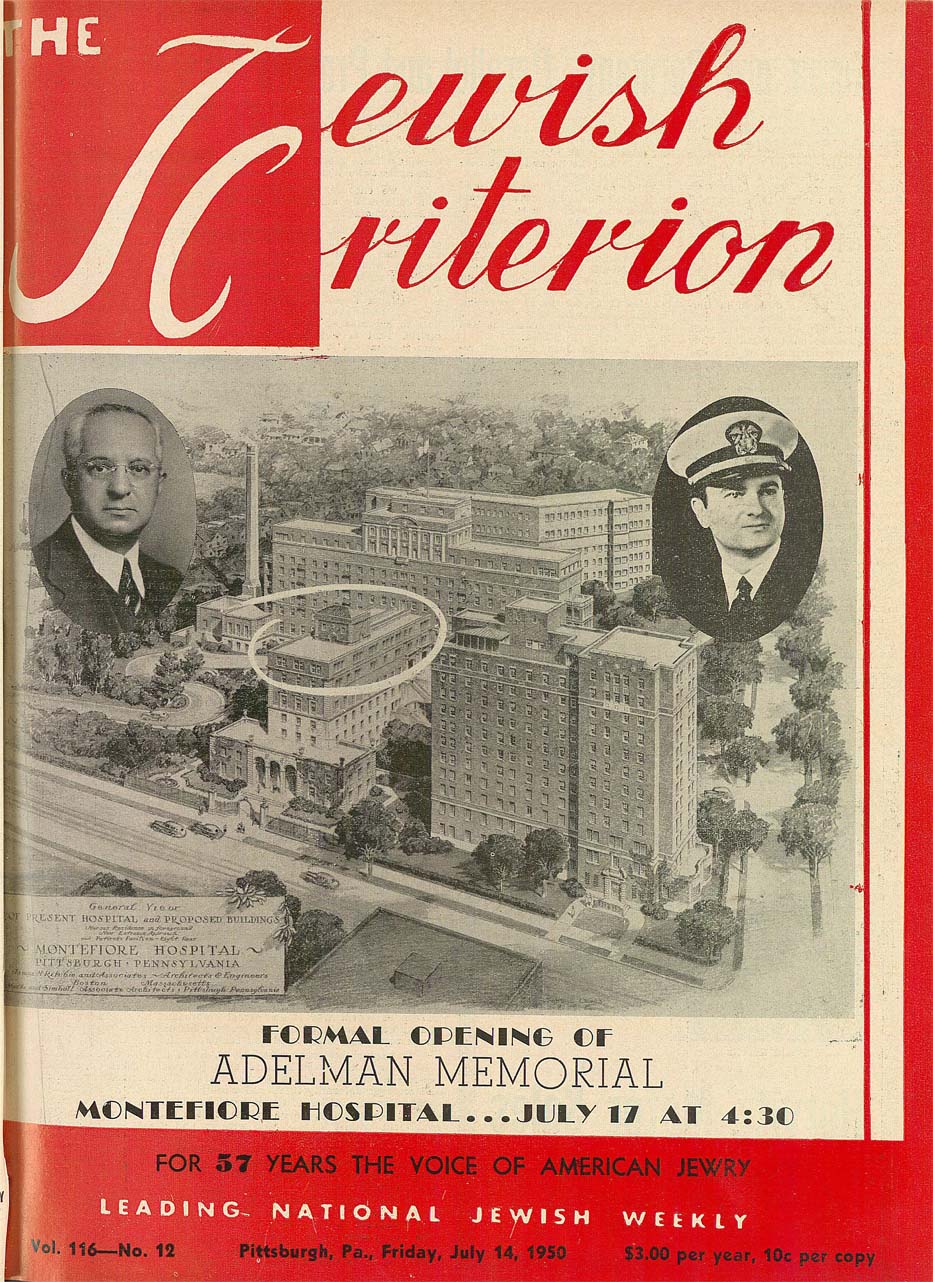

One lesson comes from the actions of the survivors. In the wake of their personal losses, three of these families undertook large communal ventures. The Chamovitzes dedicated a Jewish War Veterans post in memory of Allen. The Adelmans financed a new wing of Montefiore Hospital in memory of William. The Buchmans helped found Temple Sinai in Squirrel Hill in 1946.

Acts of philanthropy are admirable, but they are just one way of expressing grief and certainly not the only way with merit. Private grief can be just as powerful as public grief.

The defining feature of these letters is their randomness. Neither the writers nor the recipients knew that these letters would be the last. When that terrible realization came, these letters retroactively acquired the prominence and significance they have today.

But if a mailbag were to wash ashore, containing letters from each of these four men, then the last letters featured throughout this post would become next-to-last letters. They would recede into the background, and the new last letters would shine with meaning.

Death is not what makes these last letters meaningful. Death simply brings the intrinsic meaning into relief. Each moment in life is already meaningful.

These last letters ask: Why wait? Why wait until death to appreciate that meaning? Why not appreciate it now?

Eric Lidji is the director of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives.