A version of this article originally appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Western Pennsylvania History.

At 1 p.m. on the 1938 autumnal equinox, Sept. 23, the Westinghouse Time Capsule descended into a hole in the earth on the grounds of the New York World’s Fair, not to be seen again for 5,000 years. Project coordinator George E. Pendray dubbed the capsule’s distant heirs “futurians,” who in AD 6039 are intended to unearth the capsule and decipher its contents, which include reels of microfilmed text on science, religion, philosophy, engineering, and the arts, as well as over 40 articles of common use, including a toothbrush, an electric razor, money, and a baseball. It is hoped that the contents of the capsule will provide a representative sampling of 20th century civilization.

If you’ve wondered what the contents look like, an impressive replica of the Time Capsule can be viewed in the History Center’s Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation exhibition. What is not often appreciated is how quickly the project – from conception to burial – was completed. Pendray took a two-week vacation in June 1938. When he returned, he brought the idea of a “time bomb” that would preserve a “cross-section of our time” while also presenting the Westinghouse brand in a positive and forward-thinking light (the theme of the World’s Fair was “the World of Tomorrow”).

A board of directors who acknowledged its promotional value quickly approved the project. Pendray contacted dozens of specialists in all fields – archaeologists, astronomers, geophysicists, even fashion experts – seeking advice on what ought to be included in the capsule and preserved for posterity. In the span of two months, Pendray gathered the contents, prepared a “Book of Record” intended to guide future archeologists to the location of the capsule, and planned and executed the capsule’s burial ceremony.[1]

Pendray’s tireless effort to create the Westinghouse Time Capsule is well documented in a box of correspondence, news releases, photographs, and notes in the Detre Library & Archives. The correspondence, in particular, presents a mosaic of reaction from the experts Pendray consulted during the selection of the capsule’s contents. “Your letter of August 9th must have immediate reply,” wrote H.E. Howe, editor of “Industrial and Engineering Chemistry,” “though I confess that the immensity of your project to include in a capsule a cross-section of our time almost laid me low.” Conyers Read, executive secretary of the American Historical Association, misinterpreted Pendray’s request for suggestions as a request for memorabilia: “The idea is an interesting one, but, as I understand it, the capsule is to be buried for some five thousand years and I doubt if there is anything to represent the production of the American Historical Association which would not be reduced to powder in that length of time.”[2]

Others seem charmed by Pendray’s enthusiasm for the project and flattered by the chance to participate. Terry Ramsaye, editor of the Motion Picture Herald, for instance, was happy to oblige him with a “screed of about three thousand (3,000) words, addressed to Professor ‘X’, Archeologist, not to be opened until the year 6938, Anno Domini, explaining what the motion picture was and how it worked.”[3] When asked for a selection of five plays “representative of our modern day,” George Jean Nathan, then a Newsweek theater critic, promptly provided a list that includes Eugene O’Neill’s “Strange Interlude” and George Bernard Shaw’s “Too True to be Good.” “Our Town,” which earned Thornton Wilder a Pulitzer Prize that year, didn’t make the cut.

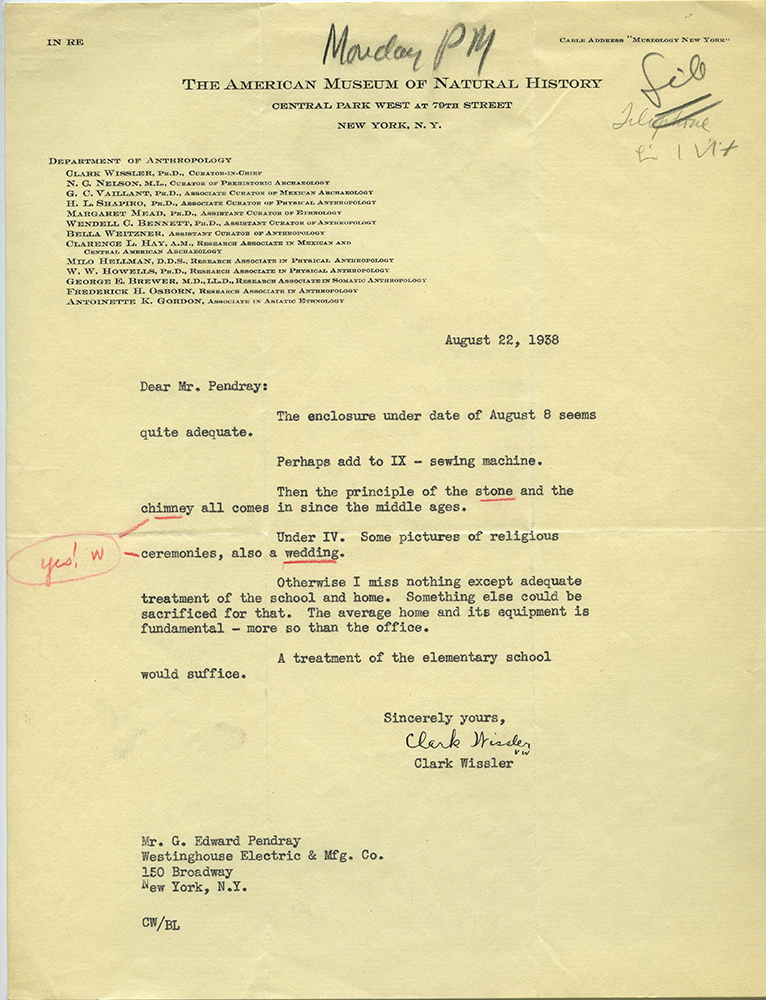

When presented with a draft of the capsule’s contents, Clark Wissler, curator-in-chief of the American Museum of Natural History, responded that it was “quite adequate” – although, he pointed out, it was missing information on the sewing machine, “the principle of the stone and the chimney,” and images of religious ceremonies and weddings. “Otherwise I miss nothing except adequate treatment of the school and home. Something else could be sacrificed for that.”[4]

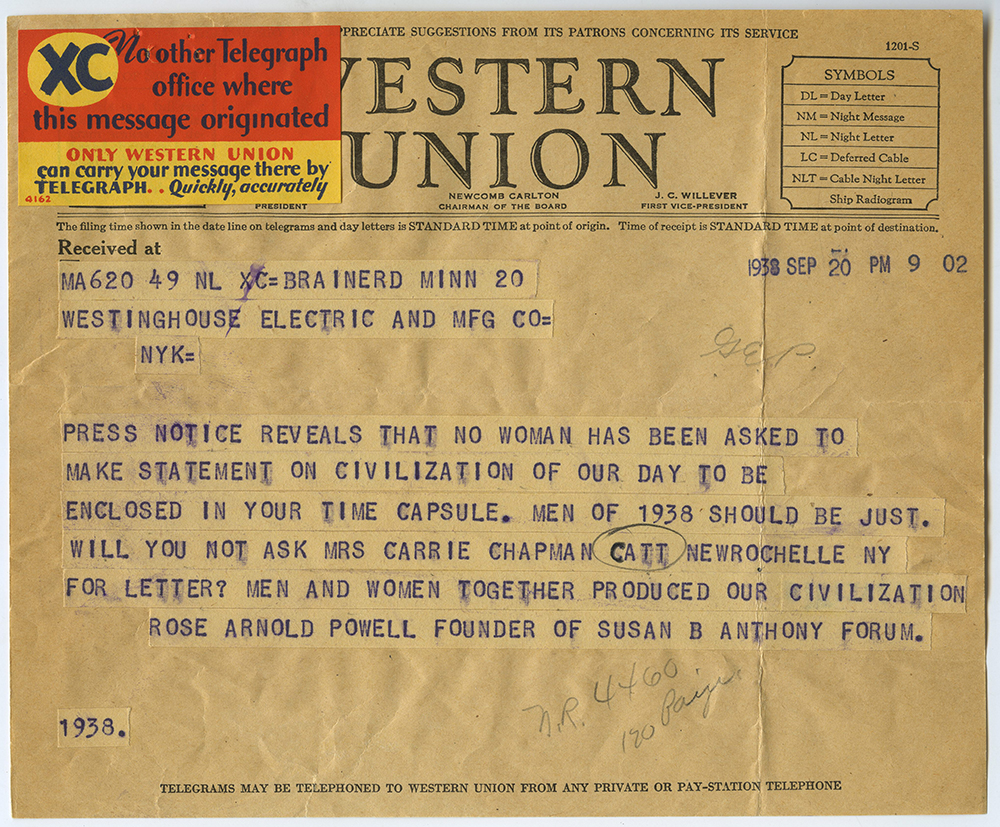

It wasn’t until after the capsule was sealed that Pendray’s method of selection revealed a regrettable consequence. Rose Arnold Powell, now remembered for her efforts to have Susan B. Anthony represented on Mount Rushmore, sent a telegram to the Westinghouse offices in New York, calling attention to a press release that publicized the messages of renowned men enclosed in the capsule. “Men and women together produced our civilization,” wrote Powell, who encouraged Westinghouse to request a statement from the women’s suffrage activist Carrie Chapman Catt. Unfortunately, there was little to be done – Catt was recovering from an automobile accident, the capsule was sealed, and the deposit ceremony was to take place in three days. Pendray, no doubt sensing an urgency to the situation, put pencil to paper in the only handwritten page included in his time capsule project files. Entitled “Things feminine in Capsule,” the document lists “Gone With the Wind,” “women’s exploits told in World Almanacs,” “several food tracts by women,” and other items in the capsule that were to represent the contributions of women in the 20th century. In his response to Powell, Pendray suggested that a duplicate capsule might be made that would include documents selected by Powell on the early history of the women’s right movement in America.

It’s unknown what came of the duplicate project, if anything, but the original time capsule remains buried below the fairgrounds in Flushing Meadows Park. It is referred to as “Time Capsule I” to distinguish it from a second time capsule created for the New York World’s Fair in 1964.

Readers interested in learning more about the details of the Westinghouse Time Capsules should contact the Detre Library & Archives to access the records of the George Westinghouse Museum Collection, which is currently being processed as part of a project funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Footnotes

[1] Terry Ramsaye to G. E. Pendray, August 17, 1938, MSS 920, Box 18.

[2] Clark Wissler to G.E. Pendray, August 22, 1938, MSS 920, Box 18.

[3] Conyers Read to G.E. Pendray, August 8, 1938, George Westinghouse Museum Collection, c.1864-2007, MSS 920, Thomas and Katherine Detre Library and Archives, Senator John Heinz History Center, Box 18.

[4] Stanley Edgar Hyman and St. Clair McKelway, “The Time Capsule,” The New Yorker, December 5, 1953.

Nicholas Hartley is the Heinz History Center’s former NHPRC Project Archivist.