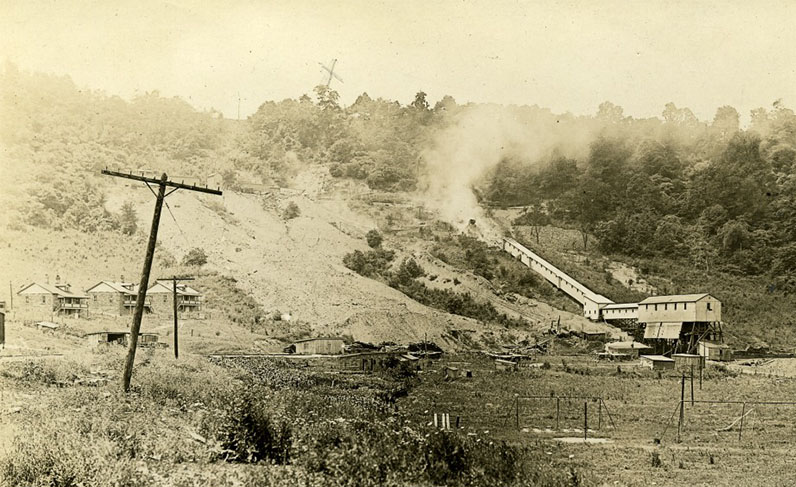

The area that was once the small mining village of Cliftonville, W.Va., sits about four miles from Avella, Pa., just across the state’s western border. Today, if you could reach the site, you might not find much. You certainly wouldn’t know that nearly a century ago, it was a fully functioning mining town of about 200 adult inhabitants, complete with a U.S. Post Office, a company store, a small train station, and, of course, a mine. There was nothing particularly special about Cliftonville until dawn on July 17, 1922, when the first shots were fired by a group of as many as 500 union miners marching on the mine in an attempt to stop nonunion miners from producing coal. When the firing subsided, at least 13 men, including Brooke County Sheriff H.H. Duval, lay dead, and many more were left wounded.

The riot at Cliftonville occurred almost four months into a strike by the United Mine Workers of America. The strike began on April 1, 1922, affecting 100% of anthracite coal production and 60% of bituminous coal production nationwide. Coincidentally, this was the same day the Richland Coal Company purchased the Saledka Mine at Cliftonville. Under the new ownership, union miners were fired and evicted from their homes in town.

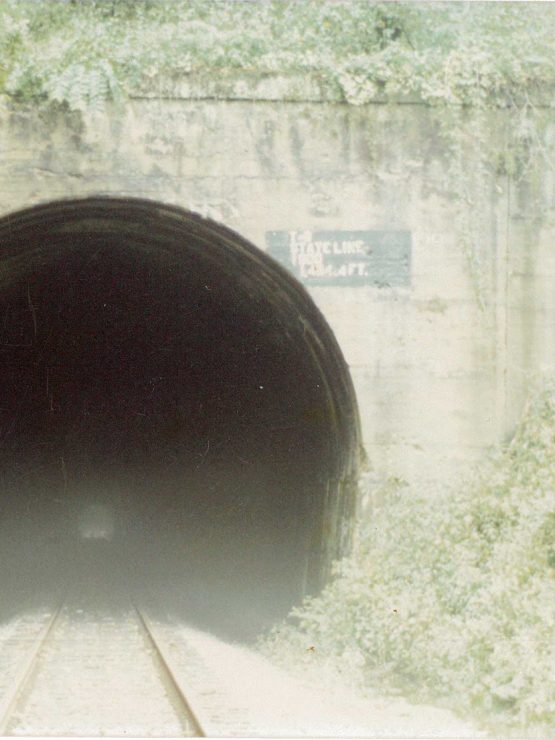

Displaced and angry, these miners and others from the area met in Avella on the night of July 16 and planned a march on the mine. Later that night, they began their march along the tracks of the Wabash Railroad, stopping at the Penowa baseball field on the Pennsylvania side of the Wabash Tunnel, where they waited for the right moment to advance. That moment came around 5 a.m., when the miners charged down the hill to capture and set fire to the mine’s tipple, used to load coal into train cars, beginning a battle that would last for almost an hour and a half.

While a general outline of what happened exists, pinning down the facts of the day is no easy task. Most information comes from personal, often conflicting, accounts, particularly those printed in local newspapers in the days following the attack. For example, Louise Bennett, who ran a Cliftonville boarding house, estimated the miners’ numbers at 500, while Thomas Duval, the sheriff’s son, believed the group was between 300 and 400 strong.[1] Even the number of fatalities is an estimate. Newspapers reporting on the riot list numbers of dead ranging from four to 13.

The personal accounts, of course, come largely from the side of the sheriff and his deputies, as miners who talked would have risked arrest during a period when almost all local police forces were on a manhunt for participants in the riot. Therefore, it is hard to get a miner’s perspective on the day. Most of their accounts come in the form of courtroom testimonies from their respective trials, where each miner likely tried to downplay his involvement in the event. Most miners claimed they were forced to join the march under threat of violence, and most men accused of being leaders in the riot denied those allegations. None would say, if they knew, who killed Sheriff Duval, and none of the 78 men indicted for his murder were found guilty of the crime.

With each passing year, Cliftonville fades further into the surrounding landscape, leaving only legend and a few scarce records behind. Some aspects of the Cliftonville Mine Riot may remain forever mysteries, enticing and evading researchers and curious minds for years to come.

Join Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Historic Village for a special program on Saturday, July 13 at noon as we shed some light on the story of Cliftonville.

[1] “Woman Eyewitness Tells of Cliftonville Battle.” The Wheeling Intelligencer, July 18, 1922.; “Slain Sheriff’s Son Tells Story of Mine Battle.” The West Virginian, July 17, 1922.

Maria Villotti is an Interpreter/Tour Guide at Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Historic Village.