Nothing quite strains our nostalgic vision of times past than a woman working hammer to anvil. While not common, history is peppered with examples of women working in metallurgy. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, a successful business – whether it is smithing or baking – was dependent on family labor. In this arrangement, there was no sexual discrimination. Each family member contributed to the shared goal of generating earned income.

Women are known to have worked alongside their fathers and husbands in the forge as early as the Middle Ages. Sometimes, widows took over their husbands’ business and were listed on guild rolls. They also registered their own maker’s marks. Woodcut artwork from the Middle Ages depicts women working at an anvil, which suggests that these women were not simply managers or figureheads, but rather direct skilled laborers participating in production.

Later, in 18th and 19th century Europe, it became quite common for women to manufacture nails and chains, particularly in England where women working as nailers outnumbered men in certain districts. Likewise, early colonists brought the European tradition of guilds and apprenticeships with them to America. Few women were known to go through an apprenticeship to become a skilled smith. Rather, women were more likely to learn alongside their fathers and husbands.

An excellent source of information about America’s labor force is the census. Started in 1790 to tally the population of the new nation, the U.S. census began recording the occupation of household members – both male and female – starting in 1860. Prior to that year, and starting in 1820, only the occupation of heads of households was recorded. It was not until the 1890 census that women were credited with the occupation of blacksmith. At that time, just 58 of the country’s 205,337 blacksmiths were women. Small numbers of women worked in other metal industries such as iron and steel workers, steam-boiler makers, gunsmiths, and locksmiths. These numbers remained rather consistent over the decades.

The majority of women at this time were not employed as heavy laborers. Rather, they were oftentimes employed as domestic servants, laundresses, teachers, or general agricultural laborers. That does provide perspective as to how news of a female blacksmith would make the rounds in the nation’s newspapers, however.

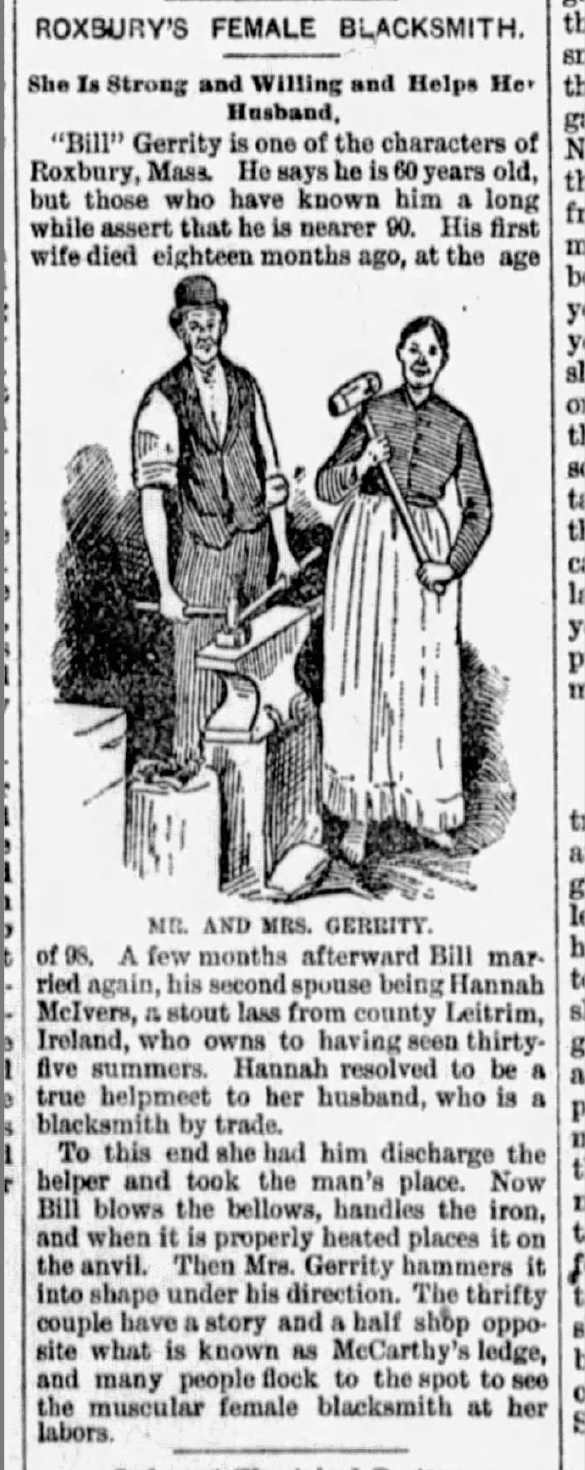

One such instance was in 1877, when Mrs. Henrietta Krause moved to Mt. Washington with her husband. The Krauses immigrated to the U.S. from Muhlhausen, Germany in 1872 and made their way to Pittsburgh in 1877. Mrs. Krause worked alongside her husband for nine years, learning the trade as his primary helpmate. So uncommon was the idea of a woman blacksmith that news of Henrietta not only made local newspapers but was also quickly picked up by national papers like The Boston Globe. In fact, newspapers would often publish tidbits whenever a female blacksmith was “discovered.” Louisville, Ky., boasted two female blacksmiths in 1879. The same year, multiple publications picked up the obituary of Rachael Yent, an “old maid” who “refused to marry, preferring to remain single and provide for the family” as a blacksmith. She was trained by her late father.

Newspaper articles depicting women smiths usually paint one of two pictures. These women are either young, beautiful, robust, and healthy girls who have been “brought up” in the work (read: just waiting to be plucked up and married) or an “immigrant other” like Mrs. Krause. The latter, like the one published in the Boston Globe, tended to feed into popular stereotypes. In that Boston Globe article, the reporter mentions Krause making a “kraut cutter.” Such derogatory idioms for German immigrants allude to the xenophobia of the late 19th century. An example of the former would be a story about Carrie and Nellie Blair, where the “lovely tinge of pink and red which ever and anon spread over face and neck … heighten her natural beauty.” The article goes on to describe the young women’s lips, teeth, and attire.

Once the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, worker safety became more of a concern, which gave society a convenient way of disguising their attempts to exclude women as concern for their safety. The louder women spoke out on equality and fair wages, the more “concerned philanthropists” pushed legislation to squeeze women out of such work.

An article published on June 17, 1882 in Kansas’ The Sliver Lake Echo reads “an extensive iron manufacturing firm of Pittsburg has opened a new field of labor for women, and will soon turn out female blacksmiths and iron workers by the hundreds.” By 1907, however, unions moved to eliminate women working in the core rooms that produced the molds for casting in foundries of Pittsburgh, where men feared women could undercut their jobs and wages. It was in these foundries that those workers producing cores were predominately, and sometimes exclusively, women. Likewise in Great Britain, where entire districts were known for the employment of females as chain makers, legislation was pursued to prohibit females in such work.

With the coming and going of the World Wars, however, women proved their place in manufacturing and other trades.

Today, though the blacksmithing occupation has long since gone by the wayside, it has enjoyed a recent resurgence as both an art and a hobby. Many noteworthy smiths are women, yet people are still surprised to see them.

Sarah Kizina is an historic interpreter at Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Historic Village.