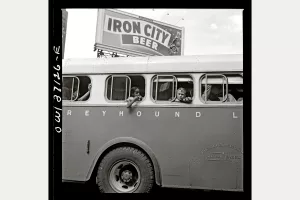

In 1943, photographer Esther Bubley snapped some of the only known interior views of Pittsburgh’s Greyhound bus station.

Esther Bubley, photographed in 1944 by John Vachon, who like Bubley, had been working for the Office of War Information. Ann Vachon.

In 1937, Pittsburgh got a new Greyhound bus station, a large, stylish terminal to replace a makeshift station in a former hotel. Dazzling as it was, the station only lasted a quarter century and is now mostly forgotten.

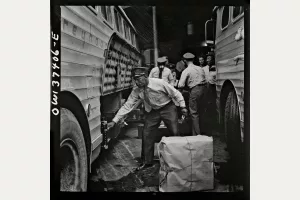

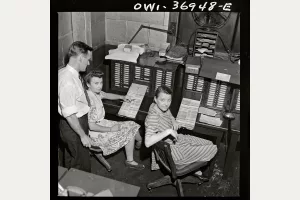

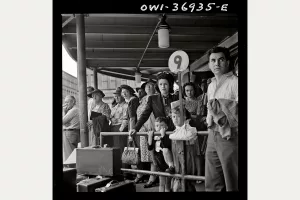

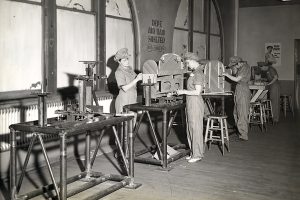

In 1943, 22-year-old photographer Esther Bubley set out on a month-long trip by Greyhound bus. Luckily for fans of Pittsburgh history, she snapped many of her photos in Pittsburgh, providing us with the only known interior views of the station.

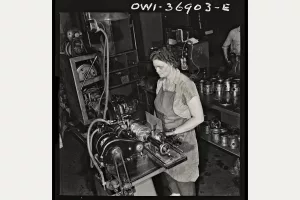

Bubley became known for taking intimate photos of people, despite lugging around a large camera. Her ability to melt into the background was a perfect fit for an assignment from the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI), bringing a human element to a propaganda agency educating the public about World War II rationing.

So, in September 1943, she grabbed the front seat on a crowded Greyhound in Washington, D.C., that headed to Baltimore, then north into Pennsylvania, where it turned westward to Pittsburgh. The bus followed two-lane U.S. 30 and the old Lincoln Highway rather than the new Pennsylvania Turnpike so that it could stop at small towns along the way.

Travel by bus had only taken hold in the 1920s. Greyhound seized the initiative to create a nationwide network of routes with stylish streamlined buses and terminals to make public transit not only acceptable but appealing, even glamorous. As war preparation escalated, Greyhound increased service to military camps and bases.

The idea of terminals, offering a variety of services and amenities around the clock, was new too. Pittsburgh’s Greyhound terminal was part of a revitalization effort at the southeastern edge of downtown that included three Art Deco buildings (Koppers, Federal Reserve Bank, and Gulf Tower) and across the street the massive Federal Building, U.S. Post Office, and Courthouse (now the Joseph F. Weis, Jr. U.S. Courthouse).

The terminal was so large that it faced both Grant Street and Liberty Avenue. The two entrances were covered in blue-face brick, with blue-cast stone for the coping. The sides had stucco above the canopy, with Kittanning brick below. Its Streamline Moderne styling continued inside with walls of canary yellow and cinnamon brown, and a ceiling of bluish-gray. Floors were terrazzo and woodwork was black walnut. Despite Greyhound hoping to be the sole operator in its own terminal, 15 other companies ended up sharing the space, drawing 320 buses to arrive and depart daily.

Bubley had gotten a job in 1942 microfilming documents for the National Archives. Respected photo documentary director Roy Stryker, who had just transferred from the Farm Security Administration to the OWI, hired Bubley as a darkroom assistant. Seeing her photography, he moved her into working on OWI assignments.

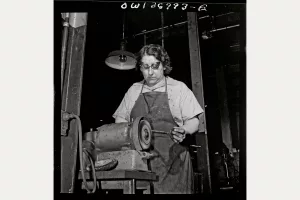

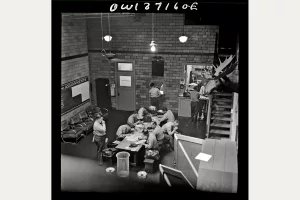

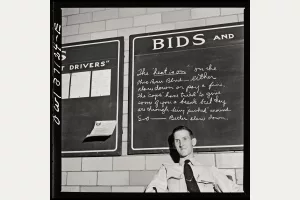

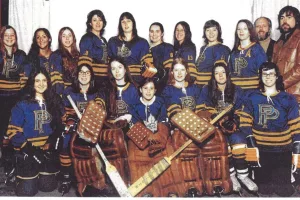

On this trip, Bubley of course documented bus passengers but she also searched out mechanics and cleaners, dispatchers and baggage handlers, and drivers at work and at rest. The Pittsburgh terminal, seen today in only a couple streetscape photos, comes alive as customers and workers go about their day. Women are notably prominent, filling jobs while men are off at war.

She submitted a report afterward, recalling some of her conversations. Long-distance passengers tended to be on vacation, while locals packed the buses to commute to work or school. She also spent time getting to know the drivers. “Red” Cochran had been with the company for 14 years and never had an accident. He typically drove 216 miles in a 10-hour day for six days, then two off, while his wife tended to their three girls. Typical driver pay was $75–$100 per week, and overnight stays were covered. As for the buses, they got about five miles per gallon.

A couple of months after this trip, Stryker left the OWI to set up a public relations project for Standard Oil Company New Jersey (SONJ); he hired away many of his former photographers who have become well-known for their work, including Gordon Parks, John Vachon, and Bubley. She would do another bus story four years later that produced even more iconic photos of industrial and agricultural scenes along with the tensions of a segregated America.

After Stryker left SONJ, he established a photographic project for the University of Pittsburgh. In 1951 he again hired Bubley, this time to document the city’s Children’s Hospital. By then Bubley was enjoying corporate assignments around the world. A decade later, however, as television replaced magazines as America’s main source of news and entertainment, Bubley left the field to concentrate on gardening and pets, publishing several books on both topics.

Pittsburgh had changed too, and a quarter century after opening, Greyhound’s Streamline Moderne architecture looked like a Model T to the Space Age generation. In 1959 a rather plain brown-and-gray Greyhound terminal opened a block away, where yet another sits today. The abandoned 1937 station was finally demolished to make way in 1964 for an even-more plain Federal Office Building.

Brian’s full story of Grant Street, Greyhound, and Bubley can be found in the Spring 2019 Western Pennsylvania History magazine, available from the History Center’s Museum Shop and for purchase online.

Also look for the blog versions here and here.

About the Author

Brian Butko is Director of Publications at the Heinz History Center, and author of books on Kennywood, Isaly’s, Roadside Attractions, and a forthcoming novel inspired by his hometown quarry.