This is a continuation of a series on the African American experience in Pittsburgh, Virginia. Click here to read part 1.

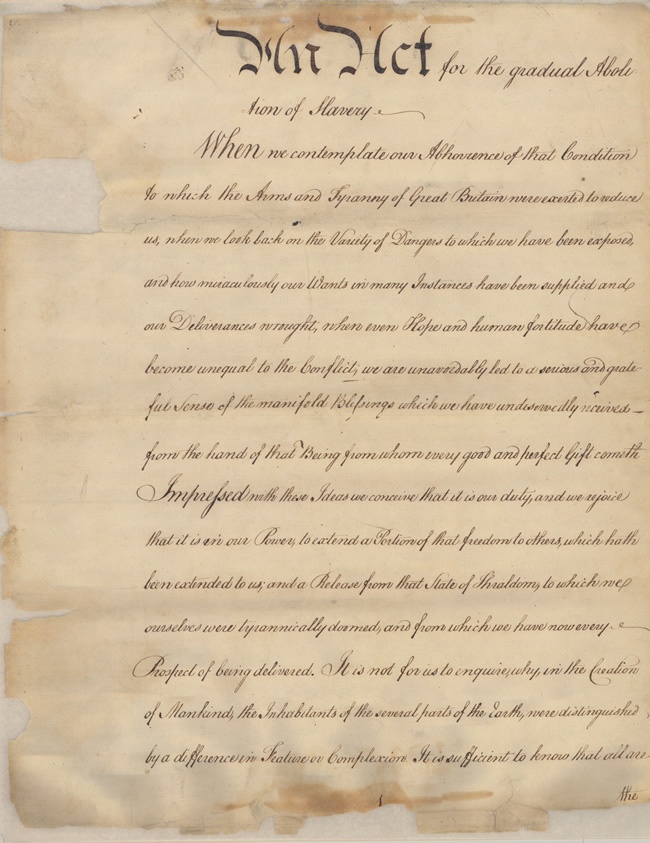

Just before the conflict between the two colonies—now states—of Pennsylvania and Virginia was resolved in 1780, Pennsylvania took steps to limit the duration and spread of slavery within its borders. Inspired by Pennsylvanians’ own fight for freedom from British oppression in the American Revolution, the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery sought to “extend a Portion of that freedom to others, which hath been extended to us.” While painfully slow to achieve its goal, the Act required individuals to register their slaves by name, age, and gender with local officials each year. In Westmoreland County, of which Pittsburgh was then a part, 200 individuals held 695 slaves, ranging in age from an 18-day-old baby boy named Anthony to a 70-year-old man named Fortymore. As human beings were expensive to own, the county’s most prominent residents, including six of its clergymen, made up the bulk of slave owners.

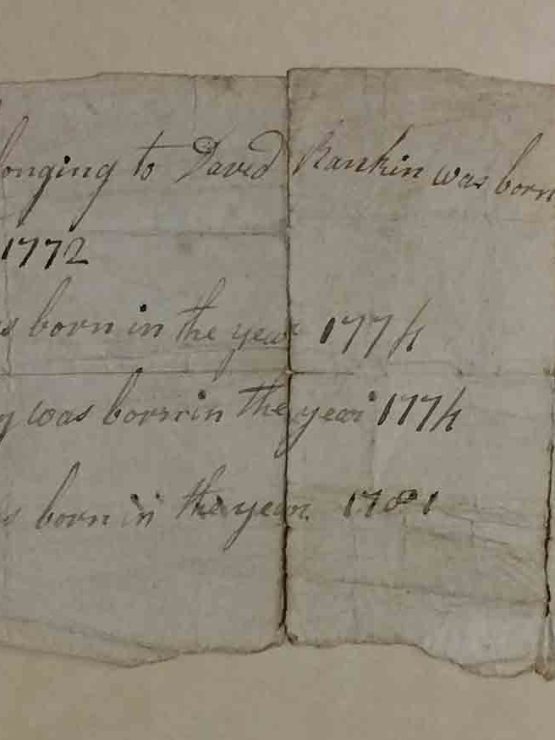

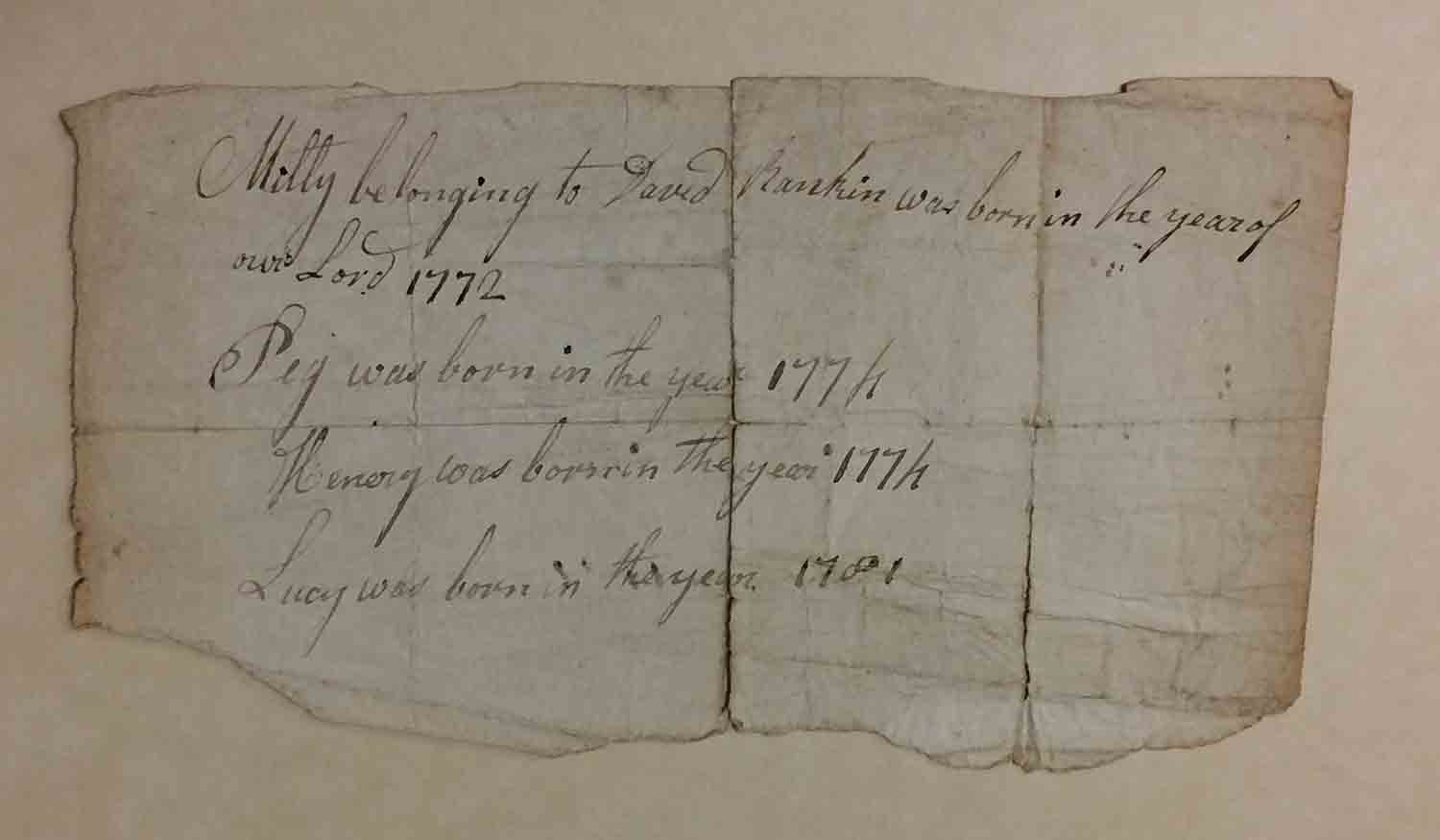

Such statistics shed tremendous light on the African American experience in early Western Pennsylvania, specifically the period from 1768 to 1780, when many slave owners, and those they held in bondage, likely entered the region. As our search for more tangible evidence continued, a newspaper article from the 1970s indicated that the original “Negro Register” for Washington County, Pa.—carved from Westmoreland County in 1781—survived intact in the collection of Washington & Jefferson College. A call to Kelly Helm, College Archivist at the Clark Family Library at W&J confirmed its existence and quickly led to more information. Not only did the college have the original Register, they also housed many of the actual handwritten notes presented by slave owners to local officials.

In contrast to the standardized look of the Register, which was essentially a copybook, the handwritten notes, dating from 1780 (when the area was still part of Westmoreland County) through the early 19th century, have a deeply personal quality that connects us directly to the people described. John Neville, one of the wealthiest men in the region from the mid-1770s onward, registered the following individuals with Prothonotary Thomas Scott in an undated note:

Molly … 30 years

Pompey … 13 D° [ditto]

Flavia … 11 D°

Dantel … 9 D°

Dick … 7 D°

Jerry … 4 D°

Lotilia … 3 D°

Joe … 1. D°

Though a step in the right direction, the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery took decades to fulfill its promise to fully eliminate the abhorrent practice in Pennsylvania. Those enslaved when the Act took effect were doomed to a life in bondage, unless they were manumitted or risked their lives to free themselves. Children born after March 1, 1780 were nominally indentured as servants to their parents’ owners until they (the children) reached the age of 28 years. The term was far longer than the standard European indenture of four to seven years, and virtually insured their continued enslavement during that period. Of the descendants of enslaved men and women in Western Pennsylvania, the children of these “indentured servants” were the first to be born truly free of the “undeserved Bondage” their parents and grandparents had endured.

Gradual Abolition of Slavery, Milly, Peg, and Henery, born before its passage, were likely to be enslaved for life. Courtesy of the Learned T. Bulman ’48 Historic Archives and Museum, Washington & Jefferson College.

These documents, a selection of which have been scanned and transcribed as part of the Fort Pitt Museum’s Pittsburgh, Virginia exhibition, show the extent to which slavery defined our region in the 18th and early 19th centuries, as well as the glacial progress of the 1780 Act for Gradual Abolition. Present in what is now Western Pennsylvania from the earliest days of European settlement, the last reference to slavery in the Washington County Negro Registry is dated 1847. Such records highlight the complexity of the African American experience in the early history of our region at the same time they underscore the gaps in our understanding and challenge us to dig deeper. Though they can be difficult to read, and perhaps impossible to fully comprehend, these artifacts of slavery also contain the first glimpse of a truly free Black community in a region that would ultimately be home to some of the nation’s most prominent African American leaders.

This blog post was adapted from research conducted for the Pittsburgh, Virginia exhibition at the Fort Pitt Museum. Special thanks to Ronalee Ciocco and Kelly Helm of the Clark Family Library, Washington & Jefferson College who provided access to the Learned T. Bulman ’48 Historic Archives and Museum, where the documents are housed, and enthusiastically agreed to place them on loan for the exhibition. Thanks, as well, to former Fort Pitt Museum interns Sarah Donovan and Hayley Madl, who also contributed excellent research on the 18th-century community of Pittsburgh.

Mike Burke is the Assistant Director of the Fort Pitt Museum.