In the summer of 1778, a crisis loomed over the hills and valleys surrounding Fort Pitt. Years of broken promises and willful transgressions had weakened the bonds between American officials at Pittsburgh and the Great Lakes and Ohio Country Indians on whose friendship they desperately depended. One by one, the Mingo, Wyandot, and Shawnee severed their ties with the Americans, siding with the British at Detroit and going on the offensive against frontier settlements.

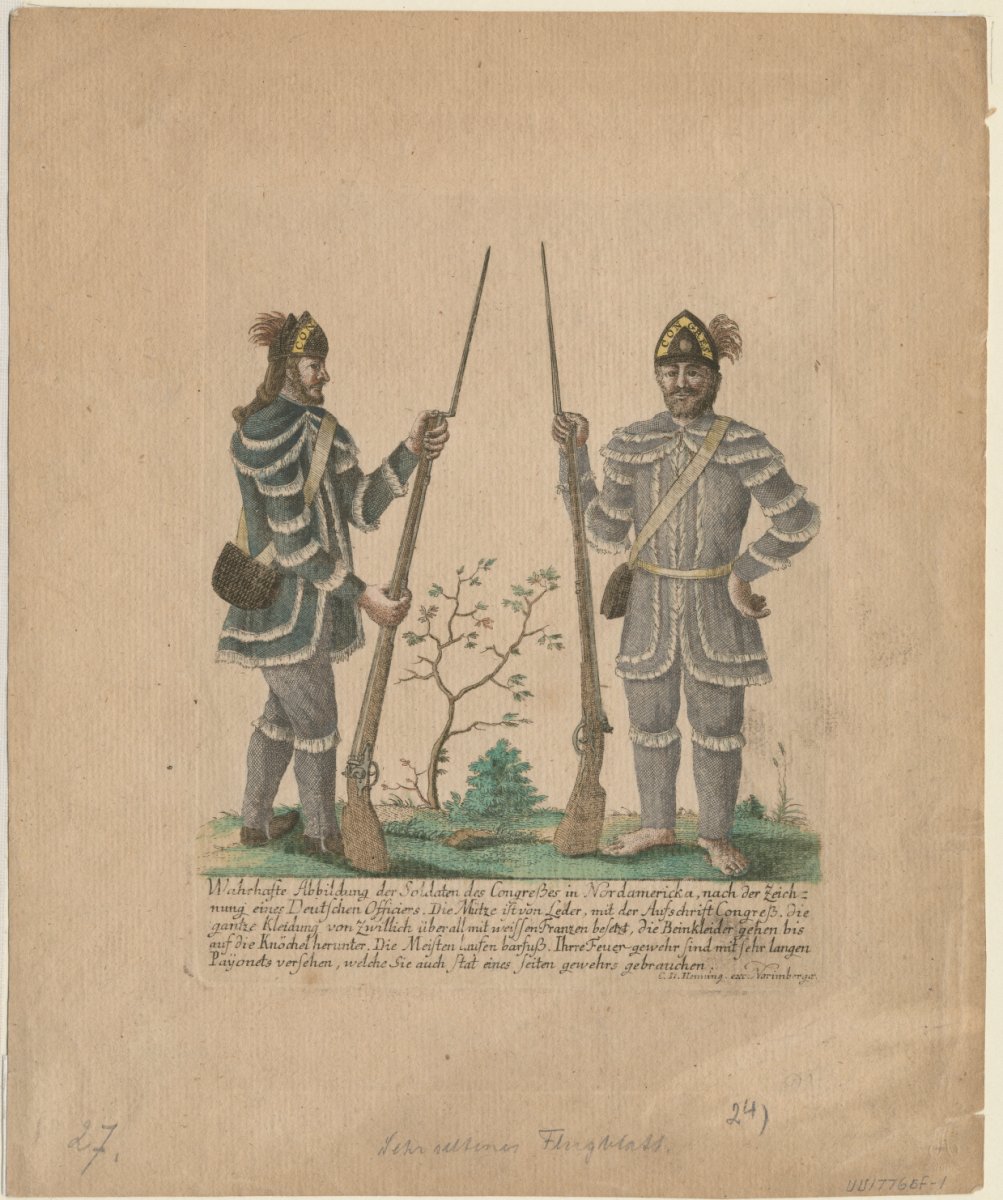

In addition to their inability to maintain relations with the region’s Indians, Continental commanders at Fort Pitt struggled to restrain their own people. As border settlers aggressively encroached on native lands, the western frontier once again became a scene of violence and retribution. Even in a military context, American leaders found their own troops, most of whom were drawn from frontier regions, nearly impossible to control. Earlier in the year, the murders of several Delaware Indian women and children by American militiamen left Continental officials enraged and exasperated. In response to this “Squaw Campaign,” as the cowardly assault came to be known, Indian department representatives Alexander McKee, Simon Girty, and others quietly departed Fort Pitt to join the British in March.

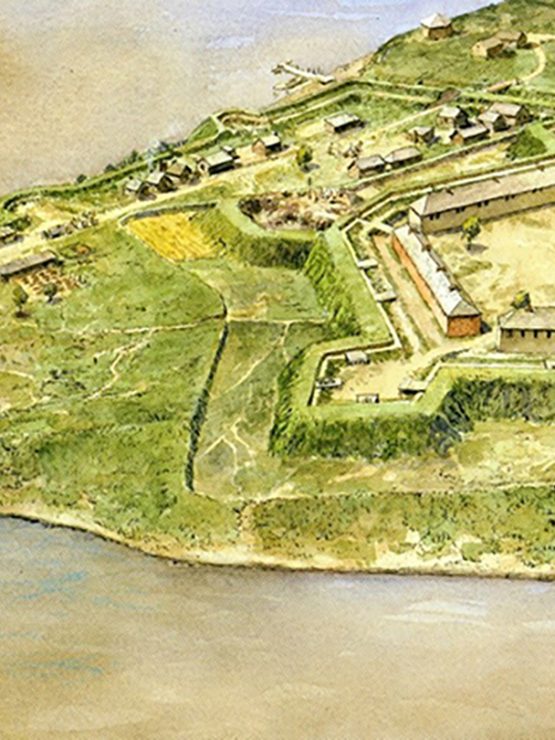

Believing that these influential men would unite the region’s Indians against them, the Americans contrived a new plan, relying ironically on the people they had most recently attacked. Along with his aides, General Lachlan McIntosh, the newly appointed Continental commander of Fort Pitt, calculated a direct strike at the British in Detroit. The attack would only be possible, however, with the permission of the Delaware people who controlled much of the territory in between. In September 1778, leaders from both sides gathered at Fort Pitt, the site of numerous prior talks and treaties, to craft a mutually beneficial agreement.

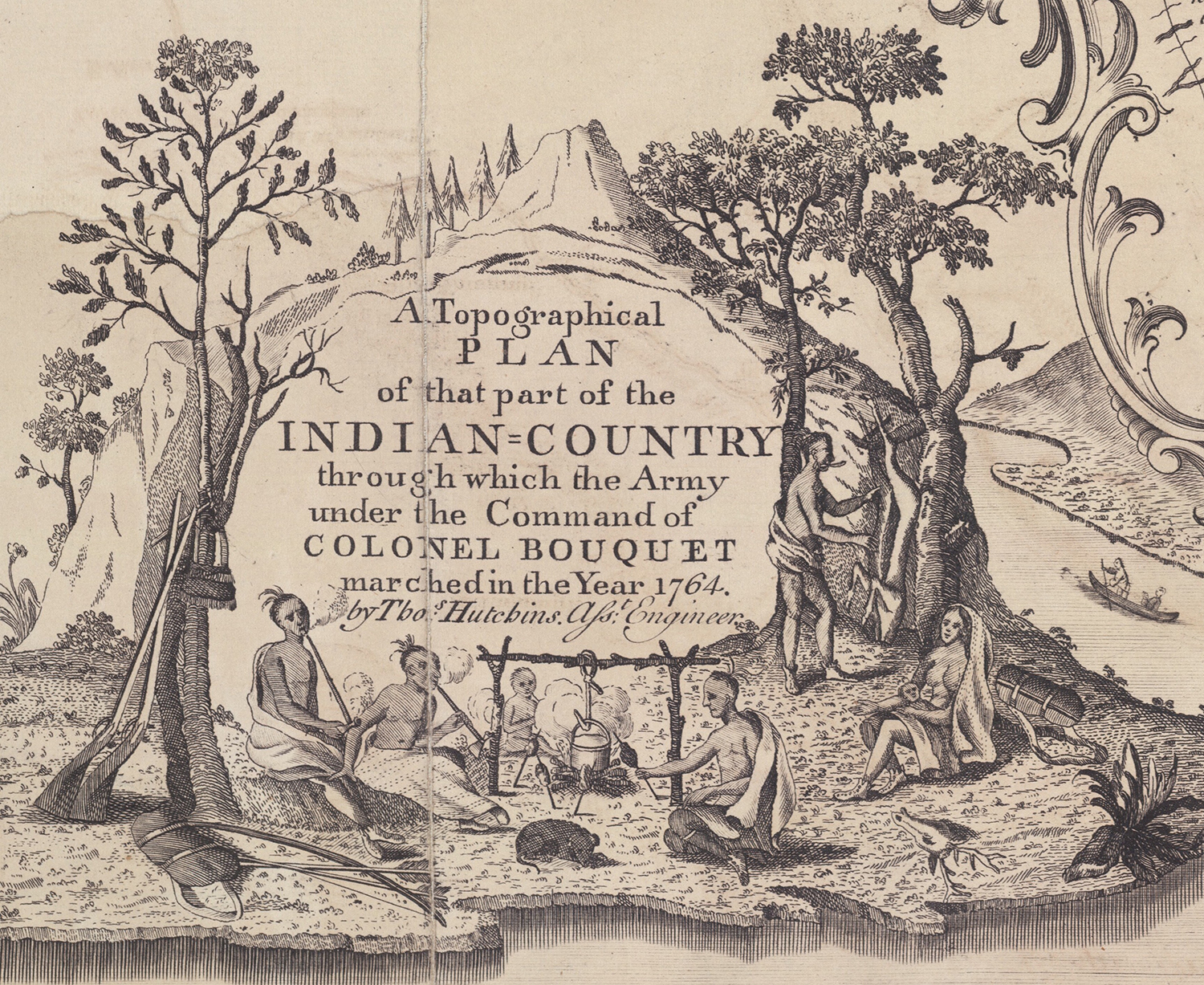

For their part, the Delaware had, up to that point, adhered to a pledge of neutrality, suffering neither the Americans, nor the British, to march an army through their country.

Now, locked in their own struggle for sovereignty, the Delaware made the fateful decision to formally side with the Americans against the British. Tribal leaders White Eyes, John Killbuck, Jr., and Captain Pipe—whose relatives had been murdered in the Squaw Campaign—granted the Americans permission to build a fort in their country. In return, the Americans promised to place the Delaware at the head of a proposed 14th American state comprised of “tribes who have been friends to the interest of the United States,” provided Congress would approve of the measure.

They never did.

Within months, White Eyes was dead, and though he officially succumbed to small pox, rumors circulated that, like so many before him, he died at the hands of his supposed American friends. MacIntosh too fell short of his goals, failing to realize his intended attack on Detroit, and limping from the region following a disastrous, and short-lived, occupation of Delaware lands. By the winter of 1778-79, the common ground sought by both sides seemed more elusive than ever.

On Sept. 29, 2018, representatives from the Delaware Tribe of Indians and the Fort Pitt Museum will join together in commemoration of the 240th anniversary of the first treaty between the United States government and a sovereign Indian nation. Though it was never ratified by Congress, the treaty represented a glimmer of hope for residents of the Ohio Country during one of the American Revolution’s darkest hours. In commemorating the event, we hope to honor those who signed it in good faith, renew a pledge to address our common history together, and brighten the Chain of Friendship that connects us. Please join us for this historic occasion.

Mike Burke is the exhibit specialist at the Fort Pitt Museum.