One of the rarest objects from the American Revolution resides at the Fort Pitt Museum in historic Point State Park. In honor of Flag Day, we’re taking a closer look at the famous standard of Colonel John Proctor’s 1st Battalion of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, one of the first military units formed west of the Allegheny Mountains. To fully understand its significance, however, it’s necessary to go back to the earliest days of the war, less than a month after Massachusetts militiamen faced down the King’s troops at Lexington and Concord.

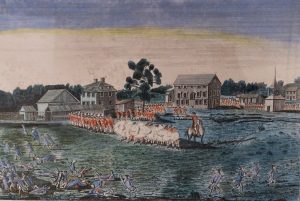

In the spring of 1775, shockwaves from New England spread like wildfire across the British colonies. In the early morning hours of April 19, British troops stationed in Boston ventured into the countryside in hopes of securing military stores reportedly kept by the would-be rebels. The shots fired on Lexington Green left several men dead and sparked a war that would forever change the course of world events.

From the opening shots, reports radiated from New England, quickly spreading the news to population centers like New York, Philadelphia, and Williamsburg. In less than a month, word reached the backcountry settlements of present-day Western Pennsylvania, nearly 600 miles away. Like their countrymen in New England, patriots near the Forks of the Ohio wasted little time in responding.

At that time, the hills surrounding Pittsburgh were home to rival factions from Pennsylvania and Virginia, with the latter controlling Fort Pitt itself, part of a district known as West Augusta. The Pennsylvanians, in turn, set up their own county seat at Hanna’s Town, Westmoreland County, a few miles northeast of present-day Greensburg. Sensing that a dispute with England was imminent, leaders of both camps had begun laying the groundwork for an organized, if not an armed, response nearly a year earlier, in the summer of 1774.

Though a bitter partisan boundary dispute still consumed much of their efforts, both the Pennsylvanians and Virginians were united in their opposition to what they saw as the tyrannical behavior of the British parliament and ministry. On May 16, 1775, leaders in Hanna’s Town unanimously declared that it had “become the indispensable duty of every American… to resist and oppose the execution of it; that for us we will be ready to oppose it with our lives and fortunes.” They further resolved to “form ourselves into a military body, to consist of companies to be made up out of the several townships under the following association, which is declared to be the association of Westmoreland County.”

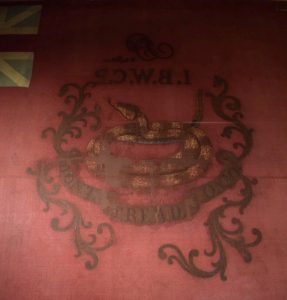

Dividing up the county’s fighting force, they created two battalions to guard the inhabitants of the frontier: one headed by John Carnaghan, and the other by John Proctor, the county’s first sheriff. While the standard of the second battalion does not survive, the flag of Proctor’s first battalion, on exhibit at the Fort Pitt Museum, remains a fascinating early artifact from this tumultuous period. Made in the fall of 1775, it is the only surviving rattlesnake flag from the American Revolution. Though the paint on its silk surface is worn with age, the imagery is still powerful and defiant. A bit of unpacking is necessary, however, to fully understand its symbolism.

A British Flag

Despite the disdain backcountry Pennsylvanians and Virginians felt for the British parliament and ministry, in the spring of 1775, they still declared an “unshaken loyalty and fidelity to His Majesty, King George the Third, whom we acknowledge to be our lawful and rightful King.” Indeed, the people of Westmoreland felt their loyalty to their sovereign was matched only by their duty to defend their rights…as Englishmen.

The flag of Col. John Proctor’s battalion is actually two flags in one. First and foremost, it is a British flag known as a “red ensign.” Flown over British naval ships and fortifications, it would have been a common sight throughout British North America. In fact, a similar flag likely flew over Fort Pitt in 1775. The ground is red silk, while the upper left quarter is occupied by the Union Flag, or Union Jack, with its white Cross of St. Andrew for Scotland, and red Cross of St. George for England.

Don’t Tread on Me

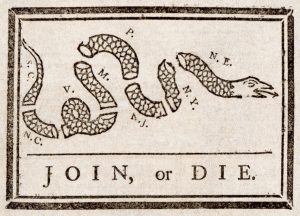

On top of this British flag is painted, somewhat defiantly, a rattlesnake with the motto “DONT. TREAD. ON. ME.” Snakes had been a symbol of the colonies since at least 1754, when Benjamin Franklin used one to make the case for the Albany Plan of Union, which warned the colonies to “Join, [against the French] or Die.” For the people of Western Pennsylvania, the native rattlesnake was particularly significant. Though its bite could be fatal, the creature preferred to avoid a fight, striking only after giving fair warning to its enemy. In December 1775, a period correspondent, who saw a similar rattlesnake and “Don’t Tread on Me” motto painted on the drum of a Marine company in Philadelphia, noted that the rattlesnake “never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders. She is, therefore, an emblem of magnanimity and true courage.” The symbol served, just as the Hanna’s Town Resolves, as a warning to would-be tyrants in Parliament and the Ministry not to tread on the rights of their fellow British subjects in America.

Other interesting features of the flag are the initials J.P. (for John Proctor) at the top of the flag, and I.B.W.C.P. (probably for 1st Battalion of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania) painted just below them.* These letters give some additional clues about the flag’s painter, as well as an indication of the order in which the work was completed. Though the painting of the rattlesnake, and the letters themselves, are skillfully rendered, the backwards lettering tells us that the artist started their work on the reverse side. Due to the relatively thin silk fabric of the original flag—which would have appeared translucent when held to the light—the letters appear backward when viewed with the Union Flag in the upper left quarter. In true 18th-century fashion, the mistake—if it was even regarded as such—was not corrected, though the subsequent wording of the “DONT. TREAD. ON. ME.” motto was painted over an opaque banner, allowing it to be read correctly from both sides.

As the war heated up following the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, Proctor’s battalion stood guard over the frontier of Westmoreland County. While a tradition has survived that the flag was never carried in battle, some of the men who served under Proctor certainly saw combat during the war. The pension deposition of Robert Lemon, or Lamon, who enlisted in August of 1776, “to do ranging services against the Indians in the Western part of the State, toward Pittsburgh,” states that his unit, of which Col. John Proctor was the commander, was called east to New Jersey in December of that year. When they arrived at Lancaster, Proctor left the unit to attend to matters at Philadelphia, but his men continued on under the command of Archibald Lochry, also of Westmoreland. Stationed near Amboy, the unit “had small skirmishes most every day until sometime in February [1777] we had an engagement with the British at what was called the Ash Swamp… at [which] place we killed a great many of the British as the deserters who came to us informed us.”

While the flag of Proctor’s battalion may never have been carried in combat, it was preserved after the war and sent, about 1810, to General Alexander Craig, who in 1775 had been the youngest officer in Proctor’s Battalion. Donated by the Craig family to the State Library of Pennsylvania in 1914, it currently resides at the Fort Pitt Museum in historic Point State Park. Due to light sensitivity, a reproduction of the flag is displayed for most of the year, while the original is on display throughout June, July, and August. If you find yourself at the Point this summer, pay a visit to Fort Pitt to see this rare survivor from the earliest days of the American Revolution.

*In a letter dated March 12, 1879 Margaret C. Craig recalled her father, to whom the flag had been given, stating that the initials stood for “Independent Brigade Westmoreland County Pennsylvania,” and that the thirteen rattles represented the original thirteen states.

Mike Burke is the exhibit specialist at the Fort Pitt Museum.