On the morning of April 13, 1758, the home of Richard and Catharine Bard, in present-day Adams County, Pa., was attacked by a party of 19 Delaware Indians. In the frantic moments that followed, husband, wife, and several others were captured, bound, and marched westward toward the Allegheny Mountains. In a twist indicative of life on a multicultural frontier, the prisoners soon found that one major barrier to communication with their captors had been removed.

As Richard Bard noted in a later deposition:

In conversation with the Indians during my Captivity, they informed me that they were all Delawares, for they mostly all Spake English, one spake as good English as I can. The Captain said he had been at Philadelphia last Winter, and another said he had been at Philadelphia about a year ago…

While none of the captives fared well on the journey, Richard’s fate appeared especially tenuous. His son Archibald later wrote of his father’s experience.

[R]eflecting that he could not possibly travel much farther, and that if this was the case, he would be immediately put to death, he determined to attempt his escape that night. Two days before this, the half of my father’s head was painted red. This denoted that a council had been held and that an equal number were for putting him to death and for keeping him alive, and that another council was to have taken place to determine the question.

After conferring with Catherine and believing his death to be imminent, Richard made a daring escape, nearly starving to death on his return home. Despite the grueling journey, Bard channeled his ancient forbears and composed a rather lengthy narrative poem that chronicled his travails. While most of the verses centered on his own suffering, the last stanza lingered on the unknown fate of his young wife.

And now from bondage though I’m freed,

Yet she that’s my beloved

Is to a land that’s far remote,

By Indians removed.

Catharine was brought to the Kuskuskies town near present-day New Castle, Pa. There, two brothers adopted her in place of a deceased sister. Before she had time to fully recover from her wounds, she was taken several hundred miles east to the headwaters of the Susquehanna River, where she lived for the remainder of her captivity. Following several desperate attempts to ransom her—one of which nearly cost him his life at the hands of the Delaware chief, White Eyes—Richard Bard succeeded in purchasing his wife’s freedom in 1760.

When she returned home, Catharine brought with her an exquisitely-crafted horn spoon made by one of her Indian family members. Made of buffalo or, perhaps, cow horn, the spoon itself was the product of an ethnically-diverse frontier where Indians and Europeans met and interacted, sometimes for war but often for peace. The form and method of manufacture—with the horn being first heated, then molded to shape—is consistent with the few other eastern woodland horn spoons from the same period, though the carvings are reminiscent of those found on colonial American powder horns.

The spoon survives today thanks to a careful chain of stewardship initiated by Catharine Bard herself. On her death, it passed into the care of her daughter Martha and has been transferred to the nearest living female descendant for over 250 years. Its nearly pristine condition is a testament to the reverence with which the family has treated it.

Like the spoon, the story of the Bards was also passed down through the generations on both sides of the cultural divide. Nearly 150 years after Catharine’s return, her great-grandson, Thomas Bard—at the time serving on the Senate Committee for Indian Affairs—had an audience with Richard Calmit Adams, a Delaware political representative, author, and descendant of White Eyes. Adams was in Washington, D.C., seeking political support for his nation, when he and Bard had a cordial meeting regarding their interconnected family histories.

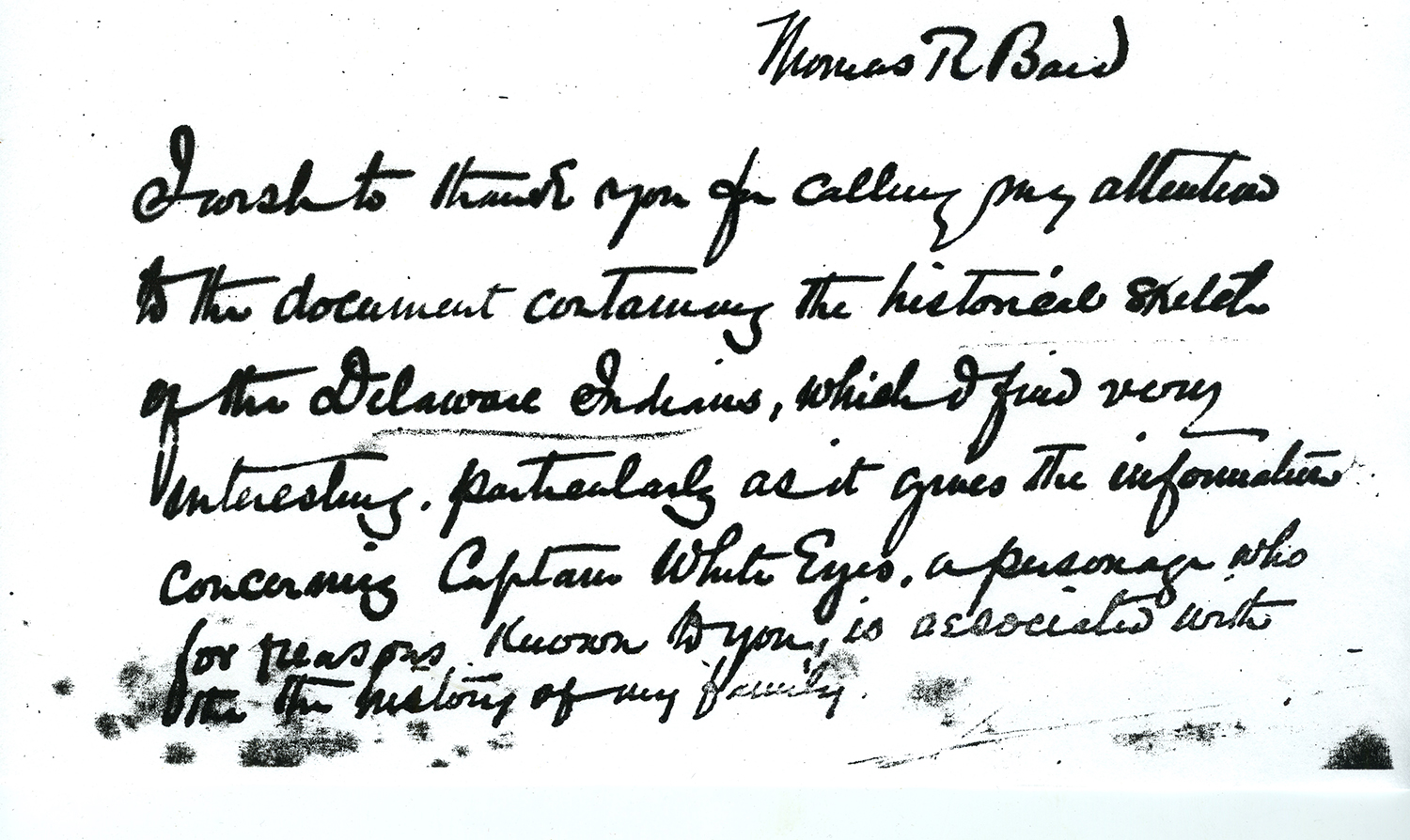

Senator Bard later thanked Adams in a letter dated Feb. 12, 1904:

I wish to thank you for calling my attention to the document containing the historical sketch of the Delaware Indians, which I find very interesting, particularly as it gives the information concerning Captain White Eyes, a personage who for reasons known to you, is associated with the history of my family.

For further reading: “The Bard Family: A History and Genealogy of the Bard’s of “Carroll’s Delight,” Together with a Chronicle of the Bards and Genealogies of the Bard Kinship,” G.O. Seilhamer, Esq. Chambersburg, Pa. (Kittochtinny Press), 1908.

Thanks to Georgia Newton Pulos and Travers Newton, Jr. of the Friends of Thomas Bard Mansion for photos and information on their ancestor’s connection with Richard Calmit Adams.

This spoon is on display at the Captured by Indians exhibit at the Fort Pitt Museum through Oct. 2.

Mike Burke is the exhibit specialist at the Fort Pitt Museum.