The years after the French and Indian War saw large numbers of Euro-American settlers pouring west over the Appalachian Mountains, steadily encroaching on American Indian lands as they defied the mountainous border meant to contain them. Spurred by the Six Nations’ cession of millions of acres south of the Ohio River at Fort Stanwix in 1768, and frontier Virginians’ victory over the Shawnee at the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774, the floodgates of settlement were opened. Driven alternately by opportunity, greed, and adventure, those who traveled down the “Beautiful River” that divided the recently ceded territory to the south from the northern country still home to the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo, and other nations, marveled at the wondrous landscape, “rich beyond conception” in natural abundance.

Joining the freshet that carried settlers deep into the interior in the spring of 1775, a 25-year-old Englishman named Nicholas Cresswell left a remarkable account of the country south and west of Fort Pitt – down the winding course of the Ohio, up the Kentucky River, and back again. Hoping to make his fortune in America, Cresswell had arrived the previous year but lost most of his savings, and nearly his life, due to a prolonged illness and a subsequent trip to Barbados to restore his health. To recoup some of his funds and obtain title to lands of his own, he agreed to travel to the distant Illinois Country to view several tracts owned by two gentlemen from Winchester, Va., making his way westward in March of 1775.

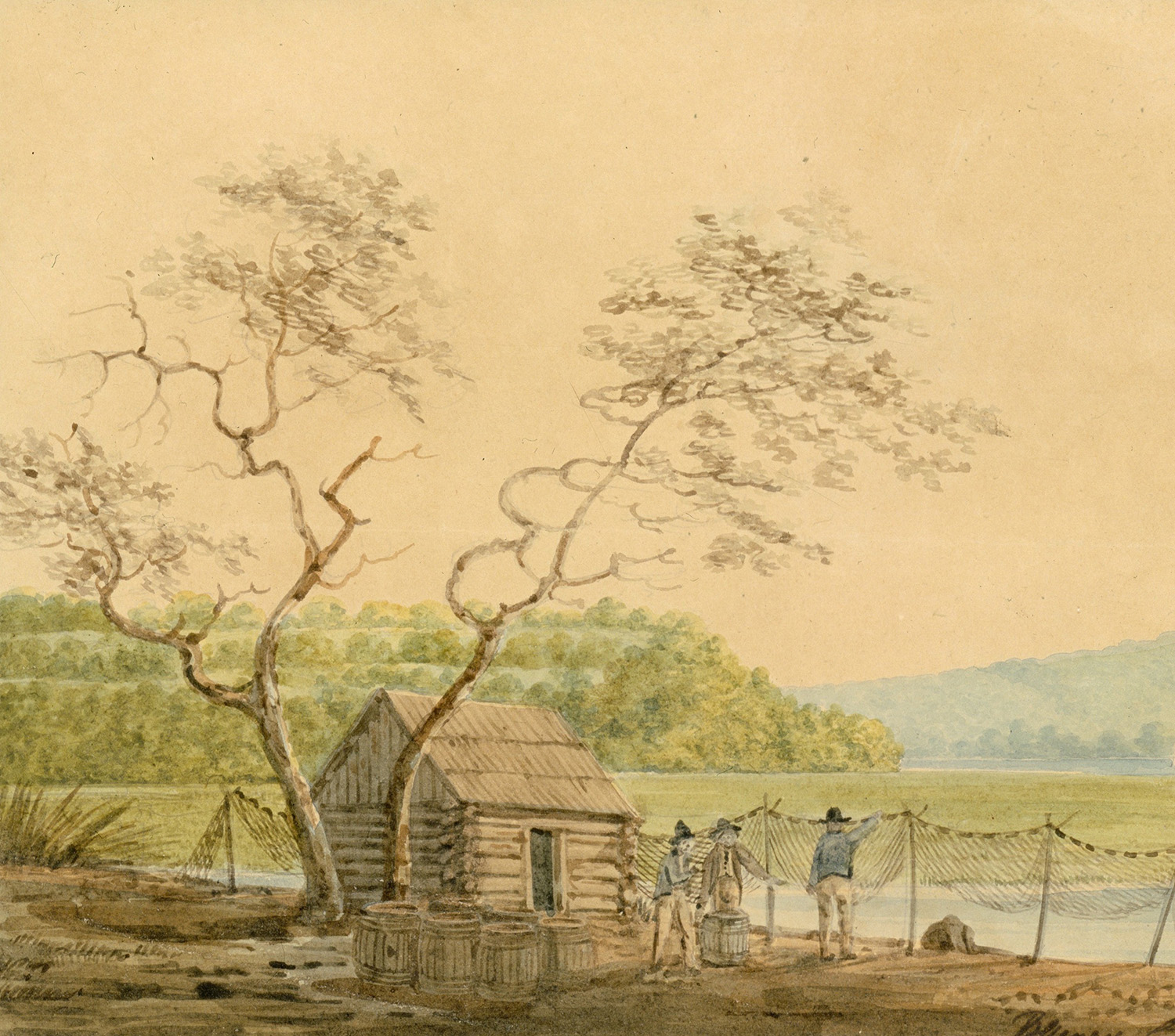

Stopping briefly in Pittsburgh (which he referred to as “Fort Pitt, Virginia”), Cresswell commissioned a pair of dugout canoes at the mostly Virginian settlement of Jacobs Creek in present-day Fayette County. From there, he and several companions guided their newly finished vessels, christened the Charming Polly and Charming Sally, down the Youghiogheny River, entering the Monongahela at “Magee’s Fort” (later McKeesport). Coming ashore at Fort Pitt to purchase “lead, flints and some silver trinkets to barter with the Indians,” the company continued down the Ohio into the heart of the contested country that had been the subject of Dunmore’s War the previous fall.

In the wake of the conflict, the risk to those hoping to claim lands on the Ohio was enormous, and those in Cresswell’s party were constantly preoccupied with fears of an Indian attack. Still, they floated on, camping and hunting on the south shore of the river whenever possible. Impressed with the natural abundance of the country, in true colonial style, they took the opportunity to kill as many large game animals as they could, with the many herds of buffalo that frequented the salt licks on the river providing a favorite target. Fascinated by their enormous prey, Cresswell described their physical appearance, as well as their culinary merits:

Buffaloes are a sort of wild cattle, but have a large hump on the top of their shoulders all black, and their necks and shoulders covered with long shaggy hair with large bunches of hair growing on their fore thighs, short horns bending forward, short noses, piercing eyes and beard like a Goat…Some of them will weigh when fat 14 to 15 hundred and are good eating, particularly the hump, which I think makes the finest steaks in the world.

During the trip, Cresswell and his companions wounded and killed numerous buffalo, though they cooked, or attempted to preserve, very little of the meat, instead taking the choicest cuts and leaving the carcasses to rot.

Having slaughtered, argued, and generally fumbled their way down the Ohio and up the Kentucky River to the recently founded settlement of Harrodsburg, Cresswell injured his foot and decided to join a small company of Virginians heading back to Fort Pitt, never having laid eyes on the Illinois Country. Days later, they fell in with a group of settlers associated with frontier ruffian Captain Michael Cresap, forming a “motley, rascally, and ragged crew” of 14 men from “almost as many different nations.” On their return trip, they stopped to gather the fossilized remains of woolly mammoths at the Big Bone Lick in present-day Kentucky. Presented with a souvenir tooth “judged by the company to weigh ten pounds” Cresswell was elated, though he flew into a rage when it was later broken by a “D-d Irish rascal” in the company. Despite having slaughtered so much game, they ran out of provisions part-way home, and were reduced to raiding deserted farms to survive.

Traveling over land from Wheeling to Redstone (present-day Brownsville) and back to Jacobs Creek, Cresswell found the clothing he left behind worn out and news of the unfolding Revolution racing through the settlement. Forced to keep his political views to himself among his “Liberty mad” neighbors, and eager to go to the Indian Country “to dispose of the Silver Trinkets” he had purchased, he arrived back at Fort Pitt in tattered clothing, several weeks before the Indian treaty being hosted by commissioners from Pennsylvania and Virginia. Hoping for one last chance to turn a profit, he joined trader John Anderson for a three-week trip to the Indian Country north of the Ohio, one that would open his eyes to people and cultures about whom he had heard many rumors, but knew very little.

Increasingly threatened by American revolutionaries upon his return, by the time Cresswell went back to England in 1777, his view of America, and its people, had shifted dramatically. The land of opportunity he hoped for had, in his eyes, revealed itself as a “hateful place” that grew increasingly vicious as the Revolution exposed the darker nature of its inhabitants. In contrast, he came to see the Indians whom he had been “taught to look upon…with contempt” as being superior “in many virtues that give real preeminence, however despicably we think of or injuriously we treat them.” Finally arriving home in fall of 1777, he re-adjusted slowly to the unadventurous life of an English farmer, and, to his surprise, found a disturbing sympathy toward the American rebels among his Derbyshire neighbors. The final entry in his journal noted his marriage to Mary Mellor of the nearby village of Idridgehay in 1781, after which he declared “My rambling is now at an end.”

In 1918, over a century after his death, a descendant of Cresswell’s named Samuel Thornley inherited his handwritten journal, and, after cleansing the most scandalous portions, had it published in New York in 1924. In the introduction, Thornley revealed that, in addition to the journal, several other objects owned by Nicholas had been preserved, including the sea-chest that contained his many souvenirs, among them an “Indian headress,” and a “bison horn, silver mounted.” No doubt harvested from one of the many buffalo he and his party had killed on the Ohio, the rough black horn—undecorated except for the inscribed silver cap added by Cresswell’s descendants around 1900—now resides in the collection of the Fort Pitt Museum. More than a natural curiosity or souvenir, it represents the exuberance of a young, and somewhat naive, traveler in a distant land, and a timely snapshot of a world that would be forever altered in the decades after his visit.

Mike Burke is the Assistant Director of the Fort Pitt Museum.