Getting streetcar service to Kenny’s Grove was fraught with drama. In 1897, the Braddock & Duquesne Street Railway was chartered (locals called it the Yellow Line for its yellow-painted cars) but like companies before it, Kenny’s neighbors did not want streetcars to cross their properties. However, the Mellons found a loophole: a public road—even one built by a private company—could use eminent domain to take the land it needed, and the road could include streetcar tracks.

With that in mind, in December 1897, Mellon money chartered the Monongahela Boulevard Company to build a road from the West Braddock Bridge (now the site of Rankin Bridge) to Duquesne. This instantly brought protests from neighbors that the company did not intend to build a road at all, just secure the right-of-way for a street railway, but the Secretary of the Commonwealth ruled it legal and issued the charter.

Four months later, the Mellons founded the Monongahela Street Railway Company to absorb the three local traction companies, with Kenny’s Grove included in the deal. When workmen began laying a 30-foot-wide brick road—with embedded rails—up to Kenny’s Grove and onward to Duquesne, the neighbors again cried foul. They sued the Boulevard company to stop it from allowing the Railway company to lay its tracks and operate its cars on the roadbed.

The Boulevard Company denied that it intended to operate a railway, or to permit any other company to do so, until consent was obtained from the landowners; it was simply including rails in its road, as allowed by law. The Street Railway Company likewise denied that it was laying the rails, agreeing with the plaintiffs that it could not lay streetcar tracks over their land. The court ruled that the intent was obvious—the two companies were one and the same and using a loophole—but neither was it illegal. And so a road with streetcar tracks was completed up past Kenny Grove and onward to Duquesne.

On November 19, 1898, Anthony Kenny leased 150 acres to William Larimer Mellon for 10 years, with an option for five additional years, for $1,600 a year plus taxes. Exactly two weeks later, the Monongahela Street Railway Company was dedicated. Attending that chilly, rainy Saturday were President Andrew Mellon and Vice President W.L. Mellon, plus directors Richard Beatty Mellon and Senator Christopher Magee. Two days later, 28 new cars (with Westinghouse motors and stoves for heat) hit the rails. The yellow paint of the Duquesne cars was applied to the entire Monongahela line, forever associating that color with the most notable landmark along its route, Kennywood Park.

But … the trolley park hadn’t yet been announced. For years, Anthony Kenny had tried giving the grove to horse enthusiasts for a half-mile racetrack, even offering to provide free ferry service from Braddock. St. Paul’s Orphan Asylum also had accepted an offer from Anthony to relocate on 50 acres adjoining his grove. But finally, on December 18, the street railway announced it had leased the Kenny farm for a park to be called Kennywood. They already had men burning underbrush and architects competing to plan it, which would include observation towers for a better view of the river, a baseball field, and possibly an auditorium. Andrew Mellon invested $25,000 in the park.

By spring 1899, residents were complaining again—Kennywood had built its lagoon right across the dirt road that, since before the Civil War, connected the hilltop down to the trail hacked out by British General Edward Braddock’s troops along the river. “Several dozen families” hesitated to use a new connecting road in the ravine (that led to the new brick boulevard) since it cut through the edge of the park where there were “No Trespass” signs.

Nonetheless, work continued, and Kennywood Park began rising from the fallow fields of Kenny’s Grove. The Monongahela Street Railway Company appointed its assistant manager, James Sansom, as supervisor of the park. The railway’s chief engineer, George S. Davison, and his civil engineering firm, Wilkins & Davison, laid out the grounds: plans and buildings were finalized on April 12, then 500 mechanics, carpenters, and gardeners were hired. They kept a small cafeteria from the grove and some cottages too, but had much more to build in less than two months.

As the weather warmed, thousands of curious visitors poured in each week checking on, and slowing, the construction progress, though the railway didn’t mind the extra fares. Thirty thousand filled the park for its grand opening on Decoration (Memorial) Day, 1899. The big attraction was a carousel built by Dentzel with three rows of animals to ride, brass rings to grab, and seating around the “Magic Circle”; its building, now home to Johnny Rockets, remains the oldest structure in the park. Also new were a two-story dance hall, bowling alley, shooting gallery, baseball field, tennis courts, cycling track, lagoon with boats to rent, and near the overlook, a Ladies Cottage with attending matron.

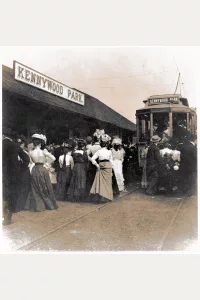

Kennywood drew a half million visitors in 1899, its first season. Most came via the Yellow Line’s 145 trolleys, and most of those trolley riders entered through a tunnel built beneath the road so that they would not have to cross the tracks. For the 1900 season, another $50,000 was spent on improvements: a band shell that could seat 200 musicians, a Ferris Wheel, and a larger ballfield with 2,000 seats, grandstand, and underground dressing rooms/showers. The park also added a roller coaster: a “Three-Way Figure 8 Toboggan Slide” built by Pittsburgher and park impresario Frederick Ingersoll on the site of today’s Sky Rocket—it was 30 feet tall and reached 10 miles per hour.

In its third season, 1901, Kennywood built a new cafeteria called the Casino—prepared meals were a relief for those tired of lugging heavy picnic baskets onto crowded streetcars. Ingersoll was operating the coaster and the Dentzel carousel, plus he built and operated Ye Old Mill where visitors found “two effigies of His Satanic Majesty … surrounded by fire and other alleged accessories of the lower regions.” The Old Mill remains, rebuilt and rethemed many times but the same basic ride.

By the end of 1901, more than a million people had visited Kennywood that season, giving its owner not only profits from the park but more than $100,000 in streetcar fares. The season concluded with a performance by popular orchestra conductor John Duss and his band playing an original composition, “The Trolley,” dedicated to the park’s leading financier, William Larimer Mellon. Kennywood was well on its way to becoming a Pittsburgh institution.

Adapted from Luna: Pittsburgh Original Lost Kennywood by Brian Butko, available at our museum shop.

About the Author

Brian Butko is Director of Publications at the Heinz History Center, and author of books on Kennywood, Isaly’s, Roadside Attractions, and a forthcoming novel inspired by his hometown quarry.