A backhoe operator excavating the site of Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Arsenal for the construction of new apartments recently discovered hundreds of Civil War-era cannonballs. The contractor alerted the bomb squad and precautions were taken to keep residents near 39th and Foster streets safe from the 150-year-old artillery projectiles. But what are these balls made of, how did they get there and how dangerous are they?

Historians long have suspected the existence of cannonball caches beneath the old arsenal site at 40th and Butler streets, a location locals today know as Arsenal Middle School and the Rite Aid pharmacy. Established in 1814, Allegheny Arsenal produced cannonballs for Commodore Matthew Perry’s fleet battling the British on Lake Erie during the War of 1812, and later became one of America’s principal ordnance innovators and manufacturers of ammunition for small arms and artillery in the years before the Civil War.

From 1861 to 1865, the sprawling complex of shops and laboratories on the banks of the Allegheny River turned out millions of rounds of musket ammunition and a wide range of shot for the horse-drawn field artillery needed by the Union armies to battle the Confederacy. So great was Pittsburgh’s wartime production that some historians refer to it as the “Arsenal of the Union.”

On Sept. 17,1862, 78 women and girls were killed, and many more wounded and maimed, in the worst industrial accident of the war. Leaking gunpowder barrels exploded at the cartridge laboratories where girls were filling paper tubes with black powder (saltpeter, charcoal and sulfur) and lead bullets for muskets.

The shops closer to the river, where men and boys loaded ammunition for artillery, were not affected by the fire. Allegheny Arsenal continued producing four types of cannonballs: Solid iron balls (solid shot), clusters or cans of small iron or lead balls (known as case shot, grapeshot or canister), exploding iron balls filled with lead shrapnel (spherical case shot) and hollow iron exploding balls (shells). These cannonballs were classified as 6-pounders, 12-pounders or 24-pounders, depending on the weight of the solid shot intended for the muzzle-loading bronze and iron cannons used during this period.

Artillerists of the day used solid shot to batter enemy fortifications, disable opposing cannons or bounce (ricochet) on the ground through massed infantry formations. Shells, though not very powerful because of the small charges of black powder they contained, were used to ignite enemy caissons (ammunition wagons) and powder magazines.

Ordnance officers long had known that canister and grapeshot were the most effective rounds. When fired at close range, the small balls in these cases scattered like a giant shotgun blast and devastated closely-packed enemy ranks. The problem was that beyond 100 yards, the small projectiles scattered too widely to be effective.

In the early 1800s, Maj. Henry Shrapnel of the British Army invented spherical case shot. He put the small projectiles inside a thin-walled hollow iron shell and added a wooden tube with slow-burning powder that could be cut to the lengths corresponding to the number of seconds the cannoneer wanted the fuse to burn before exploding the ball in front of enemy formations. The momentum of the ball would carry the iron shell fragments and small balls (shrapnel) into the opposing ranks.

The U.S. Ordnance Department soon adopted this revolutionary idea, but American officers found that the wooden and paper fuses were susceptible to moisture and shrinkage that resulted in duds or premature explosions, sometimes even before the fired round left the muzzle of the cannon.

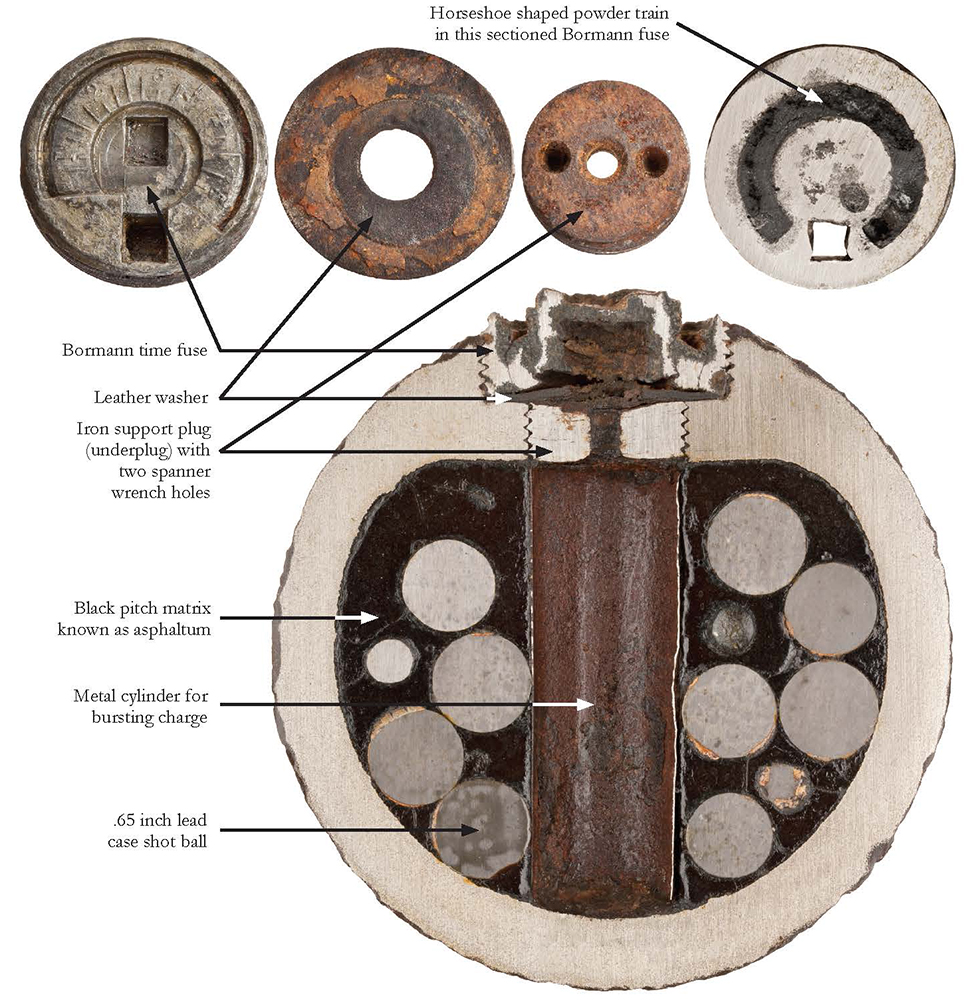

Allegheny Arsenal worked to remedy this problem and to ensure safety while storing and transporting exploding-type cannonballs in horse-drawn caissons that bounced over all kinds of roads and terrain. In the late 1850s, the arsenal began producing shells and spherical case shot fitted with Bormann fuses. This waterproof pewter fuse screwed into the iron ball. It featured a sealed powder channel that could be exposed by the gunner, who used a chisel to punch a small hole through a number (between 1 and 5) cast into the face of the fuse. The numbers corresponded to how many seconds the gunner wanted the fuse to burn. When the cannon fired, the flame of the propelling charge wrapped around the ball and ignited the exposed powder train, which in turn sparked the bursting charge after burning for the selected number of seconds.

Contrary to Hollywood films and popular lore, these cannonballs did not explode on contact. Percussion fuses were not used on spherical projectiles. These shells and spherical case shot were designed to explode only when a flame reached the interior charge. Another widely held misconception is that black powder becomes unstable over time. In fact, the opposite is true. With exposure to moisture, the saltpeter (potassium nitrate), charcoal and sulfur components degrade and, in many cases, will not even burn after 150 years in the ground.

The confusion likely results from the public’s greater familiarity with the high explosives developed after the Civil War. Alfred Nobel’s invention of nitroglycerin spawned a new era of gunpowder. Nitro-based explosives, such as dynamite, can become less stable and more dangerous over time. Hence the appropriate caution exercised by government agencies when unidentified ordnance is discovered.

Historians believe that after Allegheny Arsenal was decommissioned in 1905, stacked pyramids of obsolete cannonballs (all four types) were used as fill as new construction replaced the old buildings. In 1972, while digging footings for a warehouse fewer than 75 yards from the recently discovered cannonballs, workers found 1,250 balls, mostly 6- and 12-pounders. Most of these were packed in water-filled barrels and removed to Indiantown Gap Military Reservation and are believed to have been “exploded by the 56th Explosive Ordnance Detachment.” A number of the balls escaped destruction and were sent to Picatinny Arsenal in New Jersey. About 20 were unloaded or cut in half and examined. Some wound up in the hands of private collectors. Much information was lost to history. Only a dozen specimens found their way into the collection of the Heinz History Center, where they are exhibited today.

Archaeologists and curators are eager to examine the recent discoveries. Many questions can be answered by a careful inspection of the site and an analysis of the cannonballs. Simply weighing the projectiles and matching them to military specs can tell us whether the fused projectiles are shells or spherical case shot. Some Bormann fuses manufactured at Allegheny Arsenal bear telltale marks. Non-destructive X-ray techniques are now available that would allow researchers to safely see inside the balls.

Little is known about how the manufacture of cannonballs varied from arsenal to arsenal. If we can determine the distinctive features of Allegheny arsenal projectiles, those found at Civil War battlefields can be definitively identified. There is the possibility that after the Civil War, balls from different arsenals (perhaps even Confederate) were brought to Pittsburgh to be unloaded and subsequently discarded in a disposal pit.

The discovery of the cannonball cache at the Allegheny Arsenal site represents a rare opportunity to learn more about our history at a time when Pittsburgh was the smoky Iron City and the Arsenal of the Union during the Civil War.

Andy Masich is the president and CEO at the Senator John Heinz History Center.